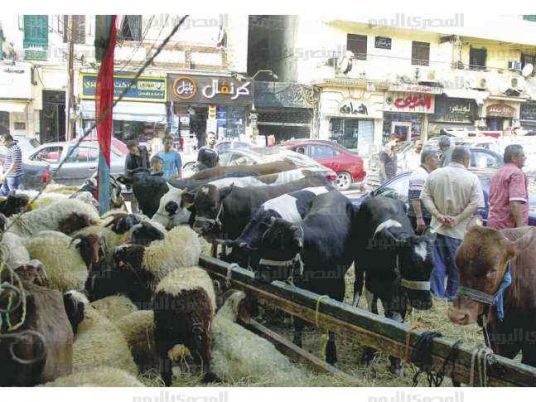

As Muslims in Egypt celebrate the Islamic Eid al-Adha feast, the most prominent ritual of the celebration is practiced: offering oblation to God by slaughtering sheep and cows before giving out their meat to the poor and family. But another problem mars the celebration: pools of blood left in the streets as the slaughtering, in most cases takes places outdoors. Add to this traffic jams caused by the sheep markets erected in the streets.

Approaching al-Gamea Square in Heliopolis, a major square in the area, horn-honking gets louder as traffic movement is strangled. Some passengers give up and resume their journeys on foot. Few steps further, the whole area’s features is obscured by a large livestock market erected outside a butchery. A mixture of ding and fodder smells irritate the nostrils of passers-by.

Kamal Mahmoud, a livestock merchant, says he has been anxious to obtain licensing from the municipality to set up his ten-day pavilion, which costs him LE5,000.

But local residents, despite their high turnout for the exhibits, are divided over whether to go along with the markets and their related problems. Ahmed Naeem, a citizen living in the area, says he can endure the makeshift markets as long as they are set up for a specific period of the year. Sanaa Ibrahim, another resident, disagrees, arguing that the pavilions hinder traffic and tarnishes the area’s civility. “Every year, we have to put up with whole streets being blocked in Heliopolis, though other alternatives could be applied, such a exhibiting the livestock in wide-open areas away from residential communities, and citizens could also arrange their purchases with the butcher without having to offer them out in the streets.”

Ahmed Abul Nasr, head of the Heliopolis local council, stressed that only butchers are permitted to exhibit their livestocks in streets in return for fees decided by the council. Abul Nasr said daily security campaigns are carried out to apprehend violators. “While the municipality works hard to remove street infringements, I am surprised to find that citizens sympathize with the merchants, telling me that their season ends within days anyway.”

In Lebanon Square, and few meters away from the “welcome to Agouza neighborhood” sign, a young man stands in the middle of a sheep herd, carrying a bundle of trefoil, while his partner wields a club to steer the sheep away from passing vehicles.

The scene raises locals’ eyebrows as they have become accustomed to pavilions rather than moving herds. Having to endure the odors and leftovers, some residents engaged in disputes with shepherds to voice anger over the practice that hinders traffic and upends the whole area.

The shepherds, on their behalf, insist on defending their business. “We are poor people and Eid al-Adha is the only season when we can sell our sheep,” says Mohamed Khalifa, the shepherd at Lebanon Square. “I wait for this season every year. In the past, I used to do my work in more populated areas like Ain Shams and Zeitoun, but people there are low-income and resort to imported meat. Customers in Mohandiseen, on the contrary, are ready with money and do not bargain so much. Their only problem is that they have to buy the sheep right after Eid prayers because they do not have a place at home to keep them, and that’s why I keep my spot at the square.”

Maamoun Ibrahim, another merchant standing in the area, said he makes sure to disappear during inspections by municipal officers but comes out from hiding again after they are gone.

In Nasr City, people frequenting exhibitions at the Cairo International Conference Center are met with ding and fodder smells after the area turned into a huge pavilion for livestock sellers who used loudspeakers to promote their exhibits. This is a case after 21 days since the tourism and shopping festival was held.

Ahmed Rabie, a young man in his twenties, labors to push a buffalo up into a truck. His mates scurry to give him a hand, fearing that clients could be hurt during the process. “This is a hard job, not everybody can take it, but I am used to it now,” says Rabie. “Its danger lies in the fact that the animal could go out of control and hurt the people around it.”

In Maadi, particularly at Thakanat district, a young man struggles to clean the area outside a consumer cooperative from livestock waste, but his efforts seemed in vain amid the high number of animals at the pavilion.

Mohamed Awad, an employee at the cooperative, said they have erected the pavilion yearly over the past 17 years. “Our first year, some residents were annoyed. Maadi has its special nature and many foreigners are living here. Over time, people got used to the scene, especially that we finish our trade on Waqfa (one day before the feast) and make sure the animals do not stray outside the wooden boundaries.”