The trial of deposed President Hosni Mubarak and his associates has raised a bundle of procedural issues, with judges, lawyers and activists disagreeing at every turn on the exact form his trial ought to take.

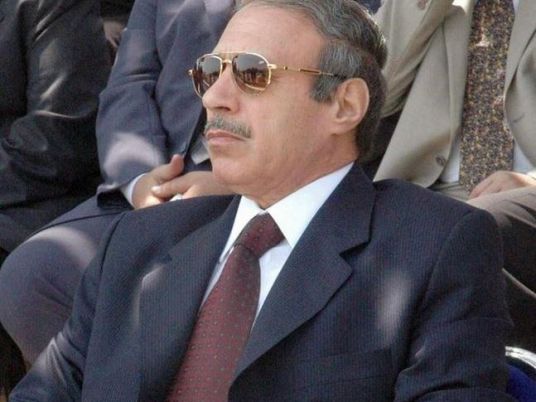

One such issue is the combining of Mubarak's case with that of former Minister of Interior Habib al-Adly. Both men stand accused of killing protesters during the 25 January uprising, a charge they face along with several senior officials. Besides conspiring to kill protesters, Mubarak is accused of squandering public funds and profiteering.

In July, Adel Gomaa, the judge overseeing the case of Adly, decided to combine his case with that of Mubarak, meaning that the court would issue one single verdict in the two cases.

In accordance with this decision, the two men appeared behind the bars of a steel cage in a Cairo court on Wednesday 3 August. However, Ahmed Refaat, the judge now presiding over the cases has yet to rule on whether or not the trials are indeed to be combined. As of the second week of Ramadan, his decision has yet to be announced.

“What happened is that the two cases are closely linked," said Sayed Fathi, a human rights lawyer acting for several of the familes of those killed in the uprising. "Mubarak is accused of ordering the killing of protesters, while those senior officials who carried out Mubarak’s orders are being tried in a different case. In such a situation, the judge would normally join the two cases and issue one verdict."

While the combining of two cases that are already highly complex seems to be tempting fate, activist and lawyer Ahmed Seif al-Islam Hamad feels the decision might lend a degree of synergy to proceedings. “This would mean simply that the case will be quicker,” he said. “I expect a verdict in around five months time.”

Aside from the practicalities, the question of whether or not to combine the cases could have implications for the sentences handed down. Some lawyers have suggested that a combined trial might be be more likely to result in the issuing of the most severe sentence possible, namely the death penalty. The theory is that in a combined trial, prosecution lawyers would be better placed to demonstrate conspiracy and premeditation on behalf of the defendents.

No doubt mindful of this, Fareed al-Deeb, lawyer for both Mubarak and Adly, has asked that his clients be heard separately. Human rights activists and lawyers for the victims' families, meanwhile, have been eager to have the two men tried together.

Yet another complicating factor is the geographic spread of the various incidents of death during the uprising, and the decision of the public prosecutor that each case should be heard by a court within the governorate concerned. There are 23 cases being heard against police officers, spread over 11 different governorates.

The implication being that for any given case of murder of a protester, there must be at least two court cases: one in the locality where the death occured, involving those police officers or other public officials who pulled the trigger; and another in Cairo for those senior figures who issued the general order to shoot protesers, meaning, of course, Hosni Mubarak and Habib al-Adly.

Some human rights activists, however, have called from the beginning for a single trial in one courtroom for all police officers accused of killing protesters, rather than individual cases in various governorates. Among them is Mahmoud Kandil, an independent human rights lawyer who has been following the Mubarak case closely.

“Such a scenario, bringing all of the police officers into one court, would have been the best scenario in which to deal with the crimes of the former regime," said Kandil. "But the public prosecutor chose to distribute the cases according to geographic jurisdiction."

Asked whether it is possible for a panel of three judges to oversee several crimes in one case, Kandil said, “In Egypt’s legal system, it’s not unusual for a judge to oversee many charges in one case. Moreover, all the charges against Mubarak are related. They are all the outcome of misuse of power by the former president.”

According to the Egyptian legal system, criminal cases are often accompanied by civil lawsuits. Both civil and criminal cases are heard in the same court, with the same judge ruling on both. The job of the prosecutor is to prove the guilt of the accused, while the task of lawyers bringing civil cases is to prove harm and seek suitable compensation.

Such is the case with the murder trials of Mubarak and Adly, and for this reason, the courtroom on Wednesday was packed with lawyers representing the families of the victims, aiming to gain compensation in civil actions running in parallel with the criminal proceedings. Alongside them were human rights lawyers and lawyers for the prosecution seeking to support the case of the public prosecutor.

Witnesses estimate that as many as 200 lawyers representing the martyrs’ families may have been present for Mubarak’s first hearing, and questions have been raised as to the competence of some of them to handle their clients' cases.

There was something of a scrum on that first day, as lawyers clamored to register their client's complaints in front of the judge. Some of the lawyers' pleas seemed a little unrealistic, with one demanding that the former president be given a DNA test to confirm his identity. Mubarak had been dead for years, said the lawyer, and the man in the cage was a body double.

“It was a disaster to have such lawyers present," said Fathi. "I can tell that some of them were happy to be at the trial of Mubarak because they were being seen on TV screens… What is alarming about the number of lawyers who were present at the Mubarak trial is that it’s impossible to unify them. They came from different geographical areas and have different motives.”

Fathi estimated that only 10 percent of the lawyers present on Wednesday are truly competent in criminal law.

Essam Sultan, a lawyer and deputy head of the Islamist Wasat Party, announced on Thursday that he has formed a joint defense team to represent the families of the martyrs, a move that might bring at least a measure of composure to proceedings.

The task of the family lawyers should also be helped along by the fact that the bulk of the responsibility for proving the guilt of the accused has already been largely shouldered by the public prosecutor.

“The charges against the defendants were prepared by the public prosecutor’s office," said Hamad. "The main challenge is not for the lawyers of the martyrs, but for the lawyers representing Mubarak and the other defendants. They have to work hard to have the charges dropped. If there is a shortcoming in the work of the lawyers of the martyrs, the public prosecutor could compensate for it.”

Regarding charges of corruption, the burden is being shared by the public prosecution and the Egyptian State Lawsuits Authority, a part of the judiciary. The Authority is responsible for bringing charges of wasting public funds, since it represents the interests of the state, from which the funds were allegedly stolen. The body has called for a combined monetary compensation of LE1 billion from the defendants, should they be found guilty.

“It is unprecedented to have a judicial body that is tasked to defend the interests of the government ask for compensation from state employees,” said Hamad.

The court is due to reconvene in a week's time, at which point lawyers are expected to begin the task of considering evidence. But with certain key issues apparently still up for debate, and no doubt some further complications yet to arise, the road to justice could be a long and bumpy one.