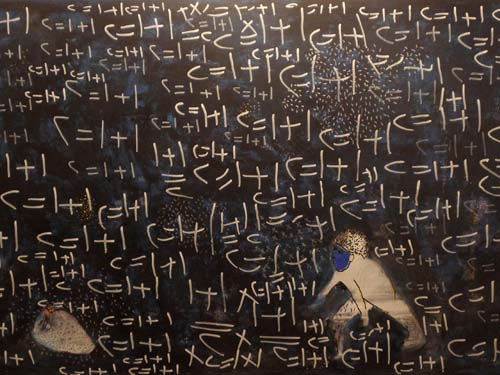

It must be a natural human urge to occasionally conjure up the most fantastic, dream-like reality possible, and give it shape, form and color. And while everyone’s imaginations will take them to uniquely fantastical landscapes, there are elements that can reliably signal the hyper or unreal. The color red, for example, has been used to represent both heightened awareness and unreality as in the case of the French short film “The Red Balloon.” In the interludes from the 1960s American sketch comedy “Laugh-In,” dancing ladies stand in the middle of swirling neon colors, removing any sense of space by eliminating clues to the physical form of the presented reality. But, the new mixed media exhibit by Italian artist Qarm Qart at Mashrabia Gallery adds a new angle to the psychedelic aesthetic.

Qart (né Carmine Cartellano) has spent the last decade of his life in Cairo. His new solo show presents works of collages, photographs of people on Egyptian streets with shiny-bubbled bright craft paper or photographs of swirling or fuzzy lights for a background. Qart works with materials that can be picked up at a basic craft store, with an eye for the playfully absurd. But his work is not just about escaping reality; it is ostensibly about building a new one. Along with glitter chairs and pink polka dots are images of Cairene streets.

For Qart, his quirky aesthetic is a way of hoping for a better future and reality. Qart told Al-Masry Al-Youm, “It is the world I’m dreaming about, full of poetry. It is like something that I want to make happen, and every one of us has to try to make it real.”

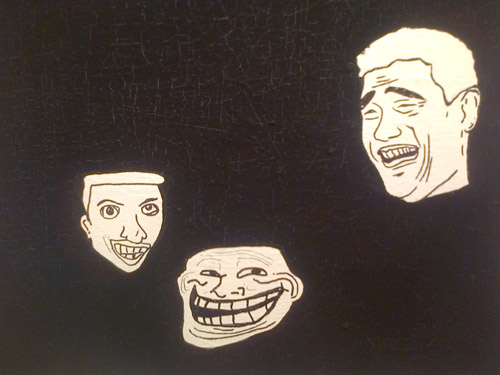

The most immediately eye-catching works in the exhibition are a group of four reinterpretations of Mubarak’s image. The image constitutes one of the more provocative pieces in the exhibition, but it is also one of few works in which Qart’s absurdist aesthetic is allowed to take over the image completely, leaving no element of realism.

The image is a standard, iconic headshot of Mubarak, but Qart has embellished it with small beads, turning the leader into Zoro, a pirate, a devil, and a clown in his four pieces.

Qart came to this project as a response to the news that Mubarak’s image would be removed from the streets of Cairo. While not a supporter of Mubarak, he was concerned about the consequences of deleting history. “I thought we should keep the pictures and draw on them,” said Qart. So he resurrected the former president in beads and bright colors.

In Qart’s kitschy portraits, Mubarak appears as an almost tragic figure as he is set in the bottom right-hand corner of an abstract photographic background displaying the digital alarm clock time “00:25.” The images play out like projections of collective imagination: Mubarak the swash-buckling hero, Mubarak the thief, Mubarak the hated and Mubarak the humiliated. In this work, Qart succeeds in creating an alternative world, where the rules are different and the imagined is real.

In other successful pieces, Qart is able to give his figures, be it a sitting policeman or a woman about to cross the street, something fun and ridiculous to share their space with, such as a collection of floating pink pigs or a giant tulip. He brightens their lives in the only way he can.

But in many works, Qart adopts too whole-heartedly the psychedelic abandonment of defined space, the result being images in which there is no integration between a real figure and an imagined environment. There are many images of police officers and poor people on the street, with titles that pose questions like “What if… there were no sexual harassment?” or “What if… all the children slept on a bed?” But the questions are external and not posed by the images themselves.

The urge behind Qart’s work is exciting in its playful absurdity. His own written description of the work – “What if… reality moves into another galaxy, where flowers are trees and freedom is air? If colors are deep and hide an inner image of yourself that becomes the hero of your own life?” – sets the stage for a truly fantastic set of images. But I found myself wishing that he would take his aesthetic further, expanding his presentation of Egypt beyond the most immediately visible figures of the streets, and constructing more complicated or more completely realized collaged scenes. As it stands, the statement the work makes is not quite fantastic enough, with a social justice message that is heartfelt and compassionate, but not developed to any degree of complexity.