Seagrasses are underwater meadows of green, lush leaves that carpet a good portion of the world’s ocean and sea beds. They are flowering plants that grow in sandy grounds, firmly rooted by rhizomes and roots. They only grow in the submerged photic zone — shallow or coastal waters that can be reached by sun rays — because they rely on photosynthesis to grow, just like any other terrestrial plant. These meadows cover over 177,000 square kilometers worldwide, and play essential ecological and environmental roles.

The seagrasses of the Red Sea have been barely studied, but the publication this month of “Field Guide to Seagrasses of the Red Sea”, by marine biologist Amgad al-Shaffai, provides records of seagrasses in this zone.

The publication of the first field guide on this submarine pasture is a first step to assess the Red Sea’s seagrasses, and raise awareness about their importance and the necessity of preventing them from decreasing.

Shaffai, marine biologist and environmental researcher at the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA), has been researching and documenting the 12 seagrass species of the Red Sea since 2006. “I have been working extensively in the protected area of Wadi al-Gamal, where I recorded 11 of the 12 species found in the entire Red Sea,” he explains.

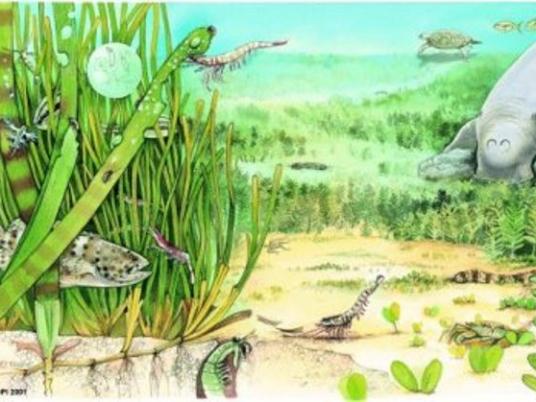

He recorded 1,500 hectares of seagrasses in this natural park, and explains that dugongs and marine turtles depend exclusively on these submarines grasses for food. Hundreds of flora and fauna species also depend on this herbivory for survival, including algae, mollusks, worms, nematodes and juvenile fish. The latter do not feed on the leaves but use this compact vegetation to hide from predators until they can freely roam the sea.

According to Shaffai, there are 40 times more flora and fauna species in zones covered by seagrasses than in areas of bare sand. He explains that “seagrasses link the mangroves and the coral reefs ecosystems together, and if one of these three intertwined ecosystem is threatened, it impacts the others.”

“Ecosystem engineers” is another term that refers to seagrasses, because they partly create their own habitat: the leaves slow down water currents and increase sedimentation while their roots and rhizomes stabilize the seabed. "Seagrasses have a very important role to play to prevent coastal erosion," Shaffai explains, "because their compactness and their roots embedded in the sandy bottom decreases dramatically the strength of waves and currents that would otherwise nibble the littoral.”

“One square meter of seagrass meadow can produce up to 10 liters of oxygen per day, that's why seagrasses are so vital to the Red Sea,” says Shaffai, adding that these meadows also serve as efficient carbon filters. He says that no less than 12 percent of global carbon is stored in ocean sediment, where the seagrasses grow. “One hectare of seagrass can filter 830kg of carbon per year, which is equivalent to the amount of carbon dioxide emitted by a 3000km car drive,” he exclaims.

There is a general lack of awareness about the important functions of seagrass on the marine ecosystem, and this has led to many occurrences of large patches of this sea meadow being uprooted to “clean up” the sandy area. A global decline of 30,000 square kilometers of sea pastures has been recorded worldwide.

The biggest threats to seagrass beds are manmade, but strong currents can also damage hectares of seagrasses. When agricultural lands are located near the coast, the fertilizer-filled wastewater that pours into the sea creates a phenomenon called “eutrophication.” Fertilizer, once in saline water, creates a vegetation bloom of brown algae which competes with seagrasses and eventually kills them. The amount of algae depletes the oxygen available in the water and reduces the amount of fish species.

Dredging to deepen harbors and waterways is also a major threat to seagrasses’ survival.

But the predominant aspect is climate change, because higher water temperatures cause coral reefs to bleach, impacting the two other connected ecosystems: the seagrasses and the mangroves.

Shaffai explains that seagrasses are unfortunately not included in any Red Sea conservation plan, but that he intends to continue his studies on these flowering underwater lawns and produce a database. “There are still many barren lands on the Red Sea coast in Upper Egypt which will soon be developed for touristic purposes: I need to have the database on seagrasses ready before it happens so we can mitigate the development’s impact on these meadows,” he says.

The “Field Guide to Seagrasses of the Red Sea”, financed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and Total, is available in PDF format and will soon be published in high quality waterproof paper in order to be carried around while scuba diving.