After passing a controversial constitutional declaration late Thursday giving himself expansive powers, President Mohamed Morsy later went on to articulate the details of the Revolution Protection Law introduced in the declaration.

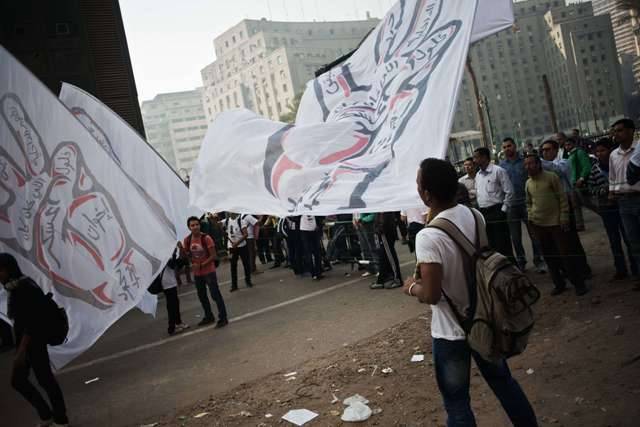

Meant to uphold revolutionary demands, the law failed to quell the anger of the thousands of protesters in Tahrir Square, who vociferously called for the downfall of Morsy and the new regime.

Although there have been numerous calls for such a law since Hosni Mubarak's ouster, Morsy's carrot-wielding is lost in the midst of what many perceived as an unprecedented power grab.

The Revolution Protection Law is sandwiched in the middle of a declaration that renders the president's decrees and laws immune from appeal or cancellation. It also protects both the Shura Council and the Islamist-dominated Constituent Assembly from dissolution by any judicial authority and extends its mandate by two months.

It also gives immunity to all decisions and decrees issued by Morsy, who also granted himself the exclusive right to take any measures he sees fit to protect the country's national unity, national security and the revolution.

The Revolution Protection Law establishes a new prosecution dedicated to investigating violations committed against protesters during the 25 January revolution, which typically refers to the 18-day uprising that toppled Mubarak and brought the military council into power. It does not, however, necessarily include investigations into the ensuing aggression committed by security and army forces against protesters in the months that followed.

The law also calls for the retrial of those who held executive posts during the time these violations occurred, including those responsible for ordering or failing to stop the killing of protesters, those complicit in hiding evidence against the perpetrators, as well as investigating cases of political and financial corruption of former regime officials.

However, the technicalities of the law may mean that retrials of former regime officials are more difficult than most people think, leaving the one upside of the declaration in shambles.

Tricky retrials

A main criticism of the new law is that it ties the retrials of former regime officials to finding new evidence.

Prosecutors of the Mubarak trial constantly complained of police and intelligence institutions being uncooperative, indirectly hinting that they hid or destroyed evidence.

"The whole concept of retrying them depends on finding new evidence. Is there any new evidence to be found? This is the question," Ahmed Ragheb, lawyer and executive director of the Hisham Mubarak Law Center, tells Egypt Independent.

Raafat Fouda, professor of constitutional law at Cairo University, says, "Those who were already sentenced cannot be retried because the same person cannot be tried twice," again unless new evidence is found.

Most police officers were found innocent due to insufficient evidence, and "you cannot just retry them because you do not like the fact they were acquitted," he adds.

Ragheb also says that although the law has been one of the main demands of rights groups, it does not establish a solid foundation for transitional justice.

For one, it fails to outline mechanisms by which the newly-established prosecution can collect evidence.

In gearing up for the trials of former regime officials and police officers involved in the killing of protesters, the prosecution's only source of evidence was police investigation records, which ultimately impeded any indictments and led to most officers walking away scot-free.

"Most of the evidence used in the trials of police officers and Mubarak was collected by the police. The law in question does not provide an alternative for this, which means we will be going around in the same circle," he says.

The types of crimes committed against protesters are somewhat out of the scope of current evidence collecting mechanisms outlined in Egyptian laws, which depend solely on probes conducted by police forces who in these cases, are themselves the accused.

Ragheb previously proposed a transitional justice law comprising mechanisms for collecting evidence mainly based on codes present in international human rights laws which Egypt is a signatory to and which are said to be more flexible and efficient.

Rights lawyer Nasser Amin says Egypt needs to ratify the Rome Statute Treaty establishing the International Criminal Court.

"If this treaty is ratified, its legal codes will be automatically part of Egypt's legal system, providing a broader context for the types of crimes in question," he says.

The law passed by Morsy using his sweeping legislative powers still functions according to the Penal Code and the Criminal Procedures Law, both not malleable enough to deal with these crimes, he adds.

Of equal importance is the law's vagueness in specifying the time period in which violations were committed against protesters, whether it encompasses violence that occurred during the reign of the military council.

The law repeatedly refers to the "former regime" and the "25 January revolutionaries." But as clashes continue around Tahrir this week, it's unclear whether protesters who come out against the new ruling powers will be considered "revolutionary."

"The decisions issued by Morsy specify exceptional pensions for martyrs including those who were killed under the military regime. The fact-finding committee appointed by Morsy to investigate crimes against protesters includes the time of military rule."

"Why this point is not clear in the new law is questionable," Ragheb adds.