Saudi Arabia’s print media landscape has just been broadened with the publication of the high-end lifestyle magazines Harper’s Bazaar Saudi and Esquire Saudi. The permission and promotion of such glossy ventures is the latest addition to Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s “Vision 2030” strategy: a social, cultural, and economic overhaul of the kingdom’s conservative rules.

“Fashion publishing has the potential to be a strong platform upon which to narrate the story of Saudi’s homegrown fashion talents and encourage cultural exchange,” Princess Noura bint Faisal Al-Saud, a leading member of Saudi Arabia’s fashion commission, said in a statement on the launch of the new magazines. The fashion commission is one of the 11 bodies that manage the growing Saudi cultural sector under the Culture Ministry’s auspices.

Only last week, the ministry appointed Burak Cakmak as head of the kingdom’s Fashion cCmmission. Cakmak, a former dean of fashion at the Parsons School of Design in New York, promised to promote “Made in KSA” (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia) as a key player in the global fashion industry.

But he also said he was aware that at the moment there is not enough information available internationally about the creativity coming out of the kingdom.

Saudis want to see Saudis

Before March 2021, the Saudi magazine market had been catered for by Arab editions, such as Harper’s Bazaar Arabia or Vogue Arabia. However, the new Saudi editions will feature domestic content by Saudi writers. For this, the publisher ITP Media Group in Dubai has set up editorial offices in Riyadh and commissioned female Saudi writers such as Alaa Balkhy, Lubna Hidayat Hussain and Marriam Mossalli and contributors such as Hala Alharithy, Hayat Osamah, Latifa Bint Saad and Norah Al Amri.

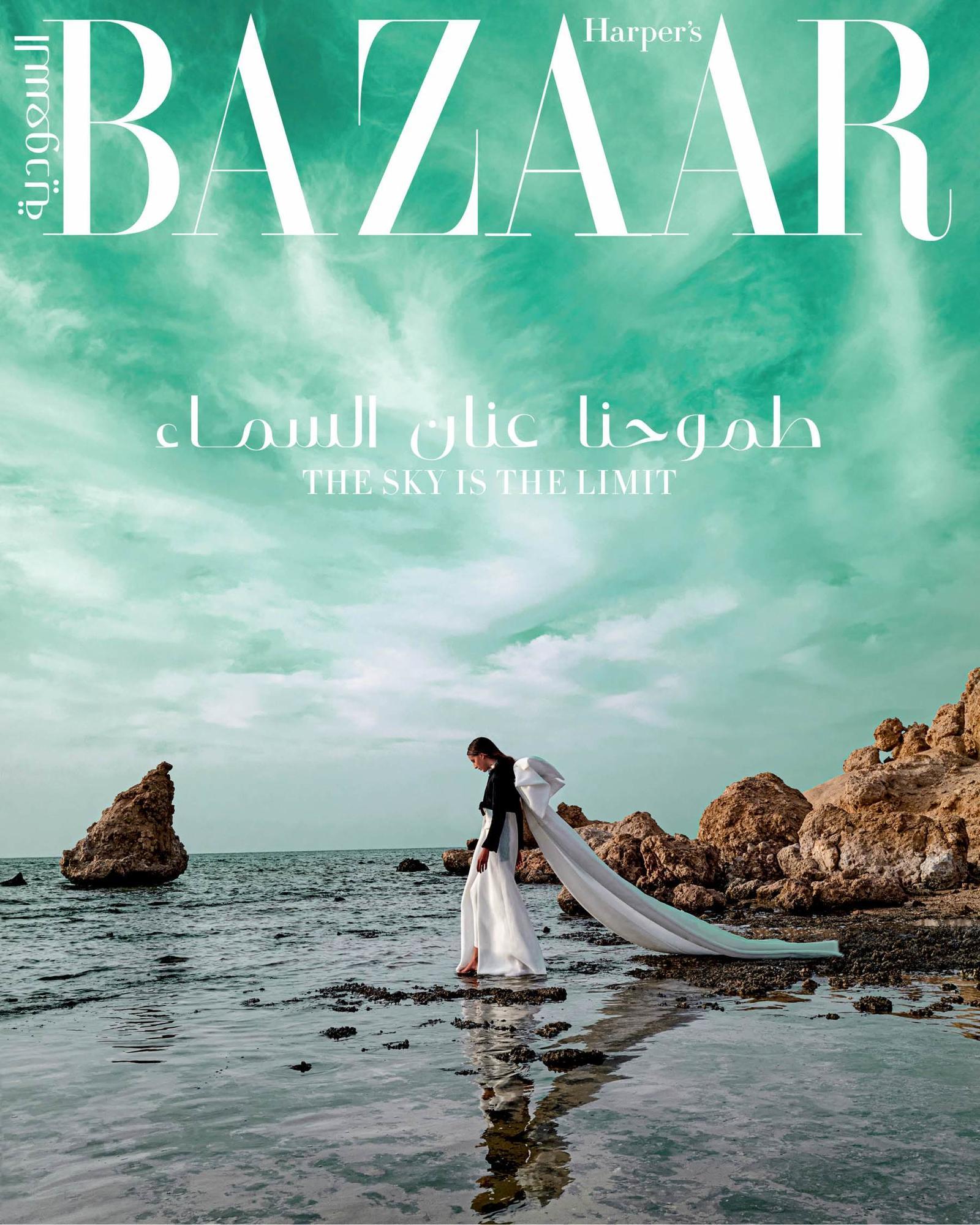

“This edition is specifically for the Saudi market. It is only distributed there print-wise, curated for the particular tastes and aesthetic of the Saudi consumer and also showcases the up and coming Saudi talent and landscapes, many of which have never been seen before,” Olivia Phillipps, the magazine’s editor-in-chief, told DW.

The bilingual English and Arabic magazines will be published biannually (Esquire Saudi) and four times a year (Harper’s Bazaar Saudi), with 100,000 copies in 2021.

Catering for couture conversation

One of the country’s fashion beacons and the contributing fashion editor of Harper’s Bazaar Saudi, Marriam Mossalli, has been fighting “stereotypes surrounding Saudi women” on Instagram, with her blog and as head of Saudi Arabia’s only luxury consultancy firm. She was the first Arab fashion expert to be invited to the White House by former first lady Michelle Obama.

“I founded my own company 10 years ago and have been witnessing how the country is progressing,” Mossalli told DW.

“For so long, we’ve been learning and using fashion terminology in a different language,” Mossalli said and names the Greek-style dress “peplum” or “jumpsuit” as examples for words that lack Arabic counterparts. “Now, we can start putting a glossary together, in Arabic.”

For Mossalli, this means harnessing the new freedom to shed more light on the local fashion market, getting more women in the workforce, and exporting Saudi fashion and culture.

Individual events suggest that change is already taking place. In January 2021, an haute couture fashion catwalk showcased modernized, open abayas (normally fully-closed black robes that are generally worn by women) that allowed seeing the ankles, and loose veils in front of a mixed-gender audience at a private event in Riyadh. Both open abayas and a mixed-gender audience would have been unthinkable in the past.

‘Fashion-washing’ while activists are imprisoned

Until now, Saudi fashion designers have rarely been in the international spotlight. Exceptions are Mohammed Ashi with his festive gowns, one of which was worn by US film director Ava Duvernay at the 2017’s Academy Awards, or Mohammed Khoja’s brand Hindamme, whose jacket “24 June 2018” was acquired by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London for their permanent fashion collection. This date marks the day when Saudi women were allowed to drive.

However, only last February, Loujain al-Hathloul, one of the group of women’s activists who drove before the ban was lifted, was set free after more than 1,000 days in prison. Other female activists who protested against the ban are still detained.

Therefore, human rights organizations like Human Rights Watch (HRW) are criticizing the new glossy fashion papers in Saudi Arabia.

“Fashion weeks and glowing leisure events are fine things that the Saudi public should enjoy. But they should also enjoy human rights. While Saudi officials heavily promote the former, they staunchly deny Saudi people the latter. That is unacceptable,” Ahmed Benchemsi, HRW’s Communications and Advocacy Director Middle East and North Africa, told DW.

He further criticized that billions of dollars are deliberately spent in PR efforts to “enhance” the image of Saudi Arabia worldwide. “But that effort is also meant to divert international attention from the kingdom’s gruesome human rights record. The record includes the killing and dismemberment of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, on top of arbitrary arrests of multiple dissidents, torture, enforced disappearances, and war crimes in Yemen.” He concludes: “No amount of fashion shows can whitewash those abuses.”

It remains to be seen if the new media outlets will include stories that address critical topics as well. The article “The Great Change: Lubna Hidayat Hussain Pens An Unflinchingly Honest, Emotional Chronicling of Saudi Arabia’s Evolution” in the first edition seems to point that way.

For now, it is safe to say that the new magazines have a huge potential market: According to the General Authority for Statistics, the country with around 35 million people has one of the youngest populations with two-thirds under the age of 35, and more than half of the university graduates are women.