AMMAN/GENEVA (Reuters) — Families fleeing air strikes and advancing troops in Syria’s Idlib province are sleeping rough in streets and olive groves, and burning toxic bundles of rubbish to stay warm in the biting winter weather, aid workers say.

Hundreds of thousands of people have been uprooted by a Syrian government assault which has corralled ever growing numbers of people into a shrinking pocket of land near the Turkish border.

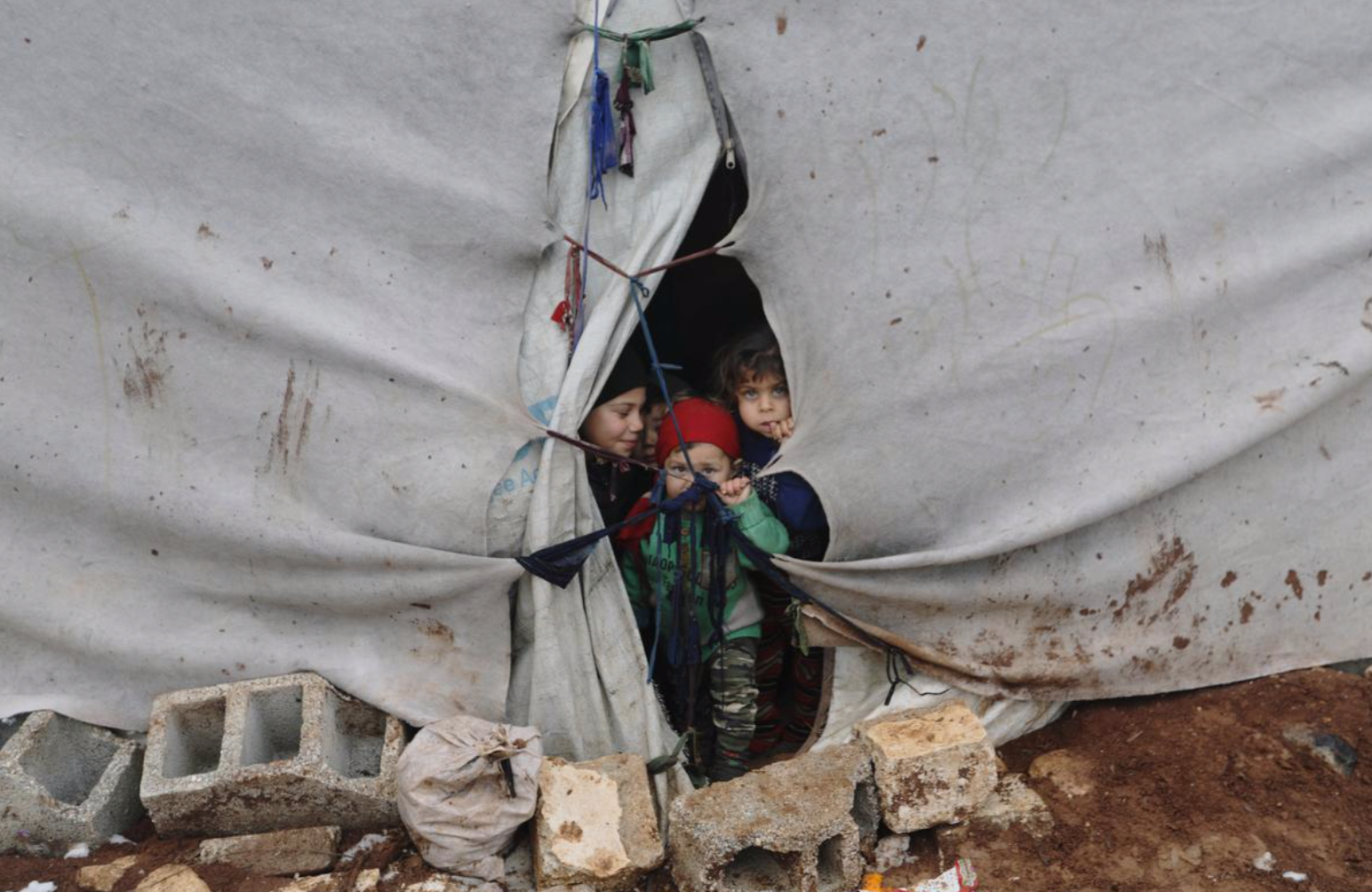

Humanitarian agency officials say it is the biggest single displacement of civilians in the nine-year-old war. But they lack the shelter and supplies to support them.

Relief workers say 10 children have died in the last week alone in makeshift camps that now dot the border area. A seemingly endless flow of cars and vehicles packed with belongings of fleeing civilians jam the roads. Some have also fled on foot.

In one camp in northern Idlib, a family of four died of suffocation on Tuesday after inhaling fumes from a fire they had made from shoes, old clothing and cardboard, their neighbor in the camp, known as Dia3, said.

“Most people are bringing bundles of shoes or clothing and burning it,” Adnan al Tayeb told Reuters by phone. “The family were sleeping and suffocated.”

The father, mother and their two children were among tens of thousands of people who had driven north to escape the Russian-backed Syrian government offensive.

Up to three million civilians are stuck between the advancing Syrian government troops and the closed-off border with Turkey, which already hosts 3.6 million Syrian refugees and says it cannot take more.

Storms which blanketed much of northwest Syria in snow this week has worsened the plight of the displaced. Shelter is scarce, with houses and tents already packed with dozens of people. Many who have become destitute have little money to buy fuel or heaters.

“People are burning anything they have available to them, things that are often dangerous to inhale just to stay warm,” said Rachel Sider of the Norwegian Refugee Council.

Mark Cutts, United Nations Deputy Regional Humanitarian Coordinator for the Syria Crisis, said the situation in Idlib was catastrophic.

“We keep hearing stories of babies and people dying as a result of cold weather and the inability to stay warm,” he said.

With the Syrian army on the outskirts of Idlib city, currently home to an estimated 1 million people, a full military assault there could lead to even greater upheaval.

‘NO PLACE LEFT’

International humanitarian agencies say the number of people on the move has swamped existing camps in northern Idlib, set up to shelter families displaced by earlier fighting, and people were being turned away.

“We are seeing people who simply have nowhere else left to go. They are being squeezed into a smaller and smaller area and are feeling very abandoned by the whole world and that the world is just failing them,” Cutts said.

The once agricultural rural terrain of Idlib province, Syria’s main olive growing district, now resembles the shanty towns on the edges of large congested cities.

“Families are sharing tents with up to 30 to 35 other people so there is very little space for people to seek refuge in northern Idlib at this stage,” Sider said.

A resident from the once sleepy border town of Atma said the many people in the human wave pouring north are now sleeping in cars and under olive trees along congested routes.

Some families, with relatives further east, are able to cross from Idlib into areas of northern Syria controlled by Turkish troops. For most, there is no escape.

“Along the border area in northern Idlib it’s overcrowded and the situation is much more difficult,” said local aid worker Adi Satouf.

Despite the turmoil and constant upheaval in the shrinking area of rebel rule, few people say they would return to areas now under the control of President Bashar al-Assad’s government.

“People are no longer thinking of returning as long as Assad is there. They are ready to put up with every injustice and hardship here but not go back to the regime,” said Ibrahim Islam, a rescue worker now struggling with his family in a camp on the outskirts of Idlib.

Reporting by Suleiman Al-Khalidi and Emma Farge; Editing by Dominic Evans and Angus MacSwan

Image: Internally displaced children look out from a tent in Azaz, Syria, on February 13, 2020 (Reuters)