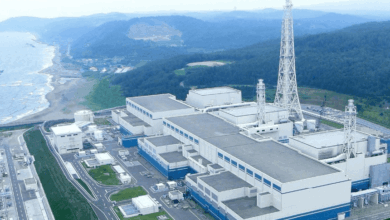

Workers were pulled back from a reactor building at Japan's earthquake-wrecked nuclear plant on Sunday after potentially lethal levels of radiation were detected in water there, a major setback for the dash to avert a catastrophic meltdown.

The operator of the facility said radiation in the water of the No. 2 reactor was measured at more than 1,000 millisieverts an hour, the highest reading so far in a crisis triggered by a massive earthquake and tsunami on March 11.

That compares with a national safety standard of 250 millisieverts over a year. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says a single dose of 1,000 millisieverts is enough to cause hemorrhaging.

The Japanese government said that, overall, the situation was unchanged at the plant — which lies 240 km (150 miles) north of Tokyo even if there were hitches from time to time.

"We did expect to run into unforeseen difficulties, and this accumulation of high radioactivity water is one such example," Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano told a news briefing.

Yukiya Amano, the director-general of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), cautioned that the nuclear emergency could go on for weeks, if not months more. "This is a very serious accident by all standards," he told the New York Times. "And it is not yet over."

Tokyo Electric Power Co engineers have been working around the clock to stabilize the situation at the Fukushima Daiichi plant since the earthquake and tsunami knocked out the back-up power system needed to cool the reactors.

The operation has had to be suspended several times due to explosions and spiking radiation levels inside the reactors, in a crisis that has become the worst nuclear emergency since Chernobyl a quarter-century ago.

On Thursday, three workers were taken to hospital from reactor No. 3 after stepping in water with radiation levels 10,000 times higher than usually found in a reactor.

LEVELS 10 MILLION TIMES ABOVE NORMAL

The latest radiation scare was confined to inside the reactor. Radiation levels in the air beyond the evacuation zone around the plant and in Tokyo have been in normal ranges.

Officials said the water in No. 2 contained 10 million times the amount of radioactive iodine than is normal in the reactor, but noted the substance had a half-life of less than an hour, meaning it would disappear within a day.

The engineers evacuated from the reactor's turbine housing unit had been trying to pump radioactive water out of the power station after it was found in buildings housing three of the six reactors.

Radiation levels in the sea off the plant rose on Sunday to 1,850 times normal just over two weeks after the disaster struck, from 1,250 on Saturday, Japan's Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency said.

"Ocean currents will disperse radiation particles and so it will be very diluted by the time it gets consumed by fish and seaweed," said Hidehiko Nishiyama, a senior agency official.

In downtown Tokyo, a Reuters reading on Sunday afternoon showed ambient radiation of 0.16 microsieverts per hour, below the global average of naturally occurring background radiation of 0.17-0.39 microsieverts per hour, a range given by the World Nuclear Association.

Several countries have banned produce and milk from Japan's nuclear crisis zone and are monitoring Japanese seafood over fears of radioactive contamination.

The accident has also triggered concern around the globe about the safety of nuclear power generation. U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said it was time to reassess the international atomic safety regime.

The crisis also looks set to claim its first, and unlikely, political casualty. In far away Germany, Chancellor Angela Merkel's party faces a defeat in a key state on Sunday, largely because of her policy U-turns on nuclear power.

OVERSHADOWING RELIEF EFFORT

The drama at the plant has overshadowed a relief and recovery effort from the magnitude 9.0 quake and the huge tsunami it triggered that left more than 27,100 people dead or missing in northeast Japan.

The first opinion poll to be taken since the disaster struck showed that approval ratings for Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan had edged higher, to 28.3 percent, but more than half disapproved of how the nuclear crisis had been handled.

Prior to the earthquake, Kan's approval rating had sunk to around 20 percent, opposition parties were blocking budget bills to force a snap election that his party was at risk of losing, and critics inside his own camp were pressing him to quit.

The survey published by Kyodo news agency on Sunday showed that nearly two-thirds of respondents were in favor of a tax increase to help fund recovery in the earthquake-torn northeast.

The government estimated last week the material damage from the catastrophe could top $300 billion, making it the world's costliest natural disaster.

In addition, power cuts have disrupted production while the drawn-out battle to prevent a meltdown at the 40-year-old plant has hurt consumer confidence and spread contamination fears well beyond Japan.

Amano, a former Japanese diplomat who made a trip to Japan after the quake, said authorities were still unsure about whether the plant's reactor cores and spent fuel were covered with the water needed to cool them.

He said he saw a few "positive signs" with the restoration of some electric power to the plant, but added: "More efforts should be done to put an end to the accident."

A Tokyo Electric official told a news conference on Saturday that experts were mulling where to put the contaminated water that plant workers have been trying to pump out of the reactors.

They also are not sure where the radiation is leaking from — whether it's from the spent-fuel rod pools or elsewhere in the reactors.

Two of the six reactors are now seen as safe but the other four are volatile, occasionally emitting steam and smoke.

At Chernobyl in Ukraine, the worst nuclear accident in the world, it took weeks to "stabilize" what remained of the reactor that exploded and months to clean up radioactive materials and cover the site with a concrete and steel sarcophagus.