While dubbed mostly Islamist, the new formation of the National Human Rights Council raises critical concerns about the entity’s mandate, members say.

The Shura Council officially declared Tuesday the final list of appointments to the 27-member council. It will be headed by Judge Hossam al-Gheriany, who also heads the Constituent Assembly, and Socialist Popular Alliance Party Abdel Ghaffar Shokr will be vice president.

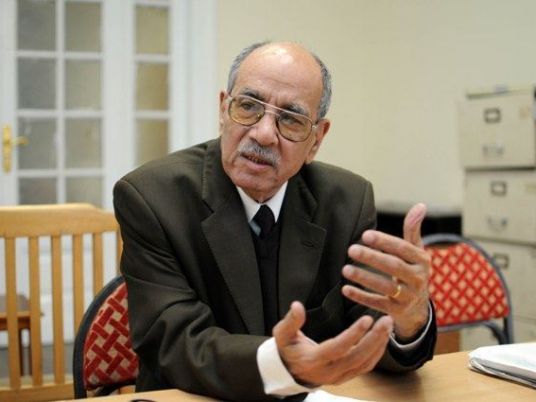

Council members include renowned rights lawyer Ahmed Seif al-Islam Hamad, leftist activist Wael Khalil, and prominent Muslim Brotherhood figures including Mohamed al-Beltagy, Safwat Hegazy and Mahmoud Ghozlan, among others.

In public discourse, the predominance of Brotherhood figures in the council has overshadowed concerns over its mandate. But for human rights defenders, who for long advocated the Islamists’ plea against the old regime’s oppression, the mandate of the council is more urgent than its political makeup.

The council’s current mandate, issued by the Shura Council in 2003, kept its role to an advisory level, allowing it issue reports and make recommendations. The council’s first formation in 2004 was dominated by members of the Hosni Mubarak regime and his now-disbanded National Democratic Party.

Beltagy tells Egypt Independent that changing the council’s mandate and its internal bylaws would be on top of his agenda to reform the performance of the council. Talk about enshrining the council’s mandate in the upcoming constitution has been on the rise.

The former Brotherhood lawmaker says the proposed new mandate would give the council the right to monitor the performance of state institutions, especially the police. The new mandate would also identify new mechanisms to translate the council’s recommendations into legally binding commitments.

Hamad, the human rights lawyer, refers to the need to intervene in two important draft laws — the Emergency Law and the law that would restructure the Interior Ministry.

“The council needs to widen its powers to laws that limit personal and civil freedoms. These two laws are very crucial to determine the fate of civil liberties and should be on top of the council’s agenda,” he said.

Furthermore, Hamad calls for widening the council’s powers to inspect prisons administered by the military, intelligence and national security bodies. The National Human Rights Council is the only human rights organization in Egypt that is legally entitled to visit civilian prisons, but with permissions from prison’s administration.

“Preventing torture and political detentions will enjoy a great consensus among the council members, and I can say that Islamists will be more enthusiastic in this regard due to their experience in this field,” Hamad argues.

In the long run, Hamad proposes that the council focus on socioeconomic rights. Yet whether the Brotherhood will allow an empowered body to monitor their performance remains unanswered.

“With the [contradicting] current formation of the council, and with the possibility of some its members to stick to their narrow party affiliations, it is very difficult to determine how empowered this council could be,” Hamad says.

Hamad also purports that consensus can be difficult over issues like freedom of thought and expression, women’s rights, freedom of religion and other minority issues.