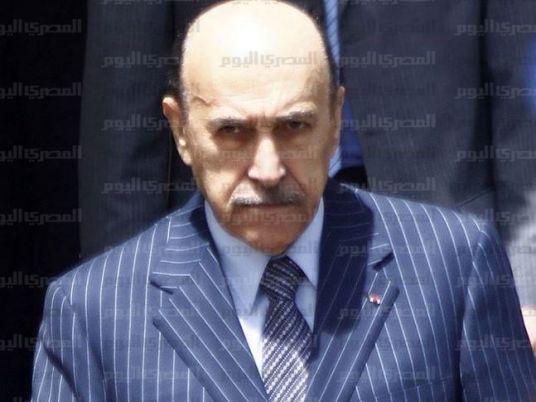

The launch at the eleventh hour of Omar Suleiman’s candidacy shows extraordinary disregard for Egypt’s popular revolution — that it happened at all, that it had clear positions against torture, normalization of relations with Israel, and America’s Middle East policy, and that former Head of General Intelligence Omar Suleiman was crucial to all of these. Suleiman’s nomination represents a bid to restore the old regime, down to its most maligned characters. More specifically, it is an attempt to entirely erase the new politics that the revolution introduced, replacing them with the classic political confrontation of the Mubarak era: that of the authoritarian regime and the Islamist opposition.

For years, this dynamic was central in Egyptian politics: Mubarak’s National Democratic Party commanded the institutions of the state, and the powers of the emergency law, while the Brotherhood had an organized base and substantial funding. The two sides battled over election fraud and detentions, but never over the neoliberal framework of the NDP nor the main features of Mubarak’s foreign policy.

In the meantime, labor movements, rights groups, and other civil society organizations were forging ties, and challenging this dynamic. When they marched together in January 2011, they offered a powerful alternative to the political reality of Mubarak’s era. It was telling that the Brotherhood leadership officially banned participation in the protests, pushing many of its youth to defy the Guidance Bureau’s orders, before leaving the group completely. After January’s uprising, a new type of revolutionary politics began to crystallize. In its vocabulary were values that carried popular consensus: social justice, freedom, human dignity and patriotism. Among its political practices were strikes, sit-ins and petitions as well as voting in free elections. And its new generation of political players included youth movements, women’s groups, leftists parties, liberals and religious conservatives — their voices beginning to make meaningful impact.

Suleiman will be the candidate to do away most flagrantly with the legitimacy of this revolutionary politics. Under the ruling military council, headed by Mubarak’s former Chief of Staff Hussein Tantawi, figures of the old regime, like Ahead Shafiq and Kamal al-Ganzouri, and former foreign minister Amr Moussa, have all been gradually imposed upon the Egyptian people, as new prime ministers and/or presidential candidates. All of them, however, have been careful to move within the confines of Egypt’s revolutionary values: Shafiq has invoked his record in wars against Israel, Ganzouri presented himself as the ‘clean’ prime minister at odds with the corrupt president, and Amr Moussa has worked hard to repackage himself as the patriot who would take Israel to task for its crimes if elected president.

But Omar Suleiman, even if he pays lip-service to the revolution, signals a different path. He was vice president at the height of Mubarak’s crackdown during the January uprising, when he told Christiane Amanpour that the Egyptian people were not ready for democracy. He spent years cultivating excellent relations with the CIA and White House, particularly by facilitating the violent human rights abuses of the rendition program. He was the broker of the Egyptian-Israeli gas deal, the conduit for Israeli pressure on Hamas during the war on Gaza, and kept the Rafah border closed during Israel’s siege of nearly two million Palestinians. He was also notoriously anti-Brotherhood, and oversaw successive crackdowns on the Islamist movement. He is now building his campaign on the ‘security’ ticket, and playing on many citizens’ fears of lawlessness or religious violence in Egypt — a threat drummed up by media outlets owned by former NDP members. Through Suleiman, the counter-revolution will be ushered further into the mainstream as a valid position and political ‘alternative.'

Meanwhile, over the past months, the Brotherhood and its Freedom and Justice Party have abandoned the revolution’s nascent coalitions, and instead played a delicate game in alliance with the SCAF, not unlike that which recurred behind the scenes between the Brotherhood and the NDP. The aim then, as now, has been to accrue the most power possible, while out-manoeuvring the political forces seeking fundamental change, hence the Islamists’ silence during the repression of popular protests since February 2011, and the SCAF’s overlooking of the FJP’s electoral violations. Last month, the latest rounds of this game culminated in an apparent standoff over the Islamists’ domination of the constitutional committee. This was followed by the Brotherhood reneging on promises not to put forth a presidential candidate, and nominating its prime financier, business tycoon Khairat al-Shater. Amidst talk that Shater’s convictions under Mubarak might disqualify him, the Brotherhood rushed to nominate FJP leader Mohamed Morsy as a back-up candidate.

Right now, several Brotherhood members and FJP MPs are in Washington on a public relations visit, on Shater’s recommendation. For some months now, the Brotherhood and its party have been visibly courting American support, and offering reassurances to Israel. In meetings with American delegations, Brotherhood members have repeatedly affirmed their respect for Egypt’s international treaties — referring directly to the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty of 1979. Meanwhile, at home, the Brotherhood’s electoral campaign is gathering momentum.

Joining the race days after Shater, Suleiman might seem to be the SCAF’s retort, with the lines of an old battle being quite literally re-drawn. There is also speculation that Suleiman — precisely because of his unpopular record under Mubarak — will boost the stakes of his more palatable counterpart from the old regime, Amr Moussa, in the context of a campaign that demonizes the Islamists. At the same time, enjoying unprecedented political opportunity since last year, the Brotherhood’s rush to gain more and more power has arguably discredited them before many prospective voters: this may well have been the SCAF’s plan all along. It should be clear that regardless of any hidden deals, the generals, like the Mubarak regime, naturally enjoy the upper hand. In 2006, Shater himself was imprisoned on charges of fraud, after the Brotherhood won more seats than it had pledged to contest in the rigged parliamentary elections.

Meanwhile, the presidential election — as with the parliamentary elections before it — has been structured to discourage or weaken any revolutionary candidates. The SCAF has exploited its powers to stall elections, influence the electoral law, and overlook violations. It has not moved to put a cap on the campaign spending limit nor oblige candidates to transparently declare their election campaign funding. And the seat of president is being contested before the executive’s powers are determined, as the constitution has not yet been written. This has led candidate Mohamed ElBaradei to quit the race, while others, such as labor rights lawyer Khaled Ali, are campaigning on, knowing there is no level playing field.

Suleiman’s campaign, performing its standoff with the Muslim Brotherhood, seeks to reduce the Egyptian political scene once again to a struggle between different brands of US-aligned free market capitalists, open to ‘doing business’ with Israel. This appears to be the final squeeze for the revolutionary political forces — but many are already describing the past year as the first round of a revolution that is only just beginning. Organizations like the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights in Egypt are renewing calls for Suleiman to be put on trial, citing files they have compiled on his role in torture and illegal abductions. If an unfair presidential race reproduces the old NDP-Islamist bipolarity, this will only rekindle the same grievances that brought millions onto Egyptian streets in January 2011.

Suleiman’s announcement came on 6 April — the anniversary of the 2008 textile workers’ strikes in Mahalla, which galvanised a new generation into anti-Mubarak activism, and generated the April 6 Youth Movement. Suleiman’s supporters bragged that the movement had been outdone by their candidate’s own feat on 6 April. But the symbolism of this date should not be taken lightly. If Suleiman is successful, the next uprising of Egypt’s popular revolution can only be a matter of time.

Reem Abou-El-Fadl is Junior Research Fellow at the Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Oxford. She has particular interests in Egyptian, Palestinian and Turkish political history.