BEIRUT, Lebanon – Syrian President Bashar al-Assad faces growing isolation as the bloodshed from his crackdown on demonstrators seeking his overthrow begins to alienate even sympathetic Arab neighbors.

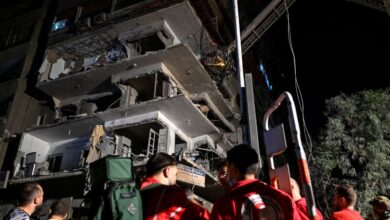

Syrian tanks stormed the eastern city of Deir al-Zor on Sunday, a week after they retook Hama, killing scores of people in an effort to crush two of the main Sunni Muslim centers of protest against Assad's minority Alawite rule.

Already facing sanctions from the United States and Europe, Assad has seen former friends in Russia and Turkey turn against him, while Arab states have broken months of silence to join the chorus of concern over the escalating violence.

"President Assad has lost all sense of humanity," a spokesman for UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said after Assad sent tanks into Hama, a move which revived memories of his father's crushing of an uprising nearly 30 years ago.

Russian President Dimitry Medvedev warned him that he faced a "sad fate" unless he curbed the violence and carried out swift reform, while Turkey's Deputy Prime Minister Bulent Arinc called the attack on Hama an atrocity.

Rights groups say Assad's repression of nearly five months of protests has killed at least 1600 civilians, and the violence has ruined years of gradual rapprochement with the West as well as growing ties with neighbouring Turkey.

Just weeks before the uprising erupted in March the 45-year-old leader, who portrays his country as a champion of Arab rights against Israel, said Syria was immune from the uprisings which overthrew leaders of Egypt and Tunisia because its foreign policy was closely aligned with popular Arab sentiment.

In a speech at Damascus University in June, one of only three public addresses he has made since the unrest began, Assad justified the crackdown and said he was overwhelmed with support from Syrians he had met to discuss the crisis.

"The love I felt from those people who represent most of the Syrian people is something I have never felt at any stage of my life," he said.

Alongside the military campaign against protests, Assad has lifted a state of emergency in place for nearly 50 years, approved laws to allow parties other than his ruling Baath Party to be established, and promised to hold a national dialogue.

His characteristically ambiguous stance, mixing iron-fisted security while holding out the promise of change, helped to mute international criticism in the early stages of the uprising.

He was able to rally tens of thousands of people for public shows of loyalty and ensured that Syria's two main cities of Damascus and Aleppo were ring-fenced from the biggest protests.

But he also said criminals and religious extremists, backed by foreign powers, were exploiting the protests. "What is happening today has nothing to do with development or reform. What is happening is sabotage…There is no political solution for those who carry weapons and kill," he said.

THRUST INTO SPOTLIGHT

The tall, quiet-spoken Assad was thrust into the spotlight after the death of his elder brother Basel in a car crash in 1994. Called back from medical studies in London, he gradually assumed a higher profile and six years later inherited the presidency when his father died after ruling Syria for 30 years.

To allow the 34-year-old to assume power, Syria's parliament met hastily to amend a constitutional clause requiring the president to be at least 40 years old.

In office, he held out the promise of reforming one of the Arab world's most tightly controlled states and oversaw a short-lived move toward political freedoms before his "Damascus Spring" fizzled out in renewed wave of repression and arrests.

Assad also strengthened his father's strategic alliance with Iran and supported militant Islamist groups including the Palestinian Hamas and the Lebanese Shia group Hizbullah.

He ended nearly three decades of Syrian military presence in neighbouring Lebanon under international pressure following the 2005 assassination of Lebanese statesman Rafik al-Hariri.

But the collapse in January of Beirut's pro-Western government, led by Hariri's son, was the latest sign that Assad has clawed back influence in Lebanese politics.

Although he backs anti-Israel militants, he also pursued indirect peace talks with Israel and, despite continued Israeli occupation of the Golan Heights captured from Syria in the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, ensured the front line usually remained quiet.

At home he started liberalising the economy, easing decades of central control and allowing limited foreign investment. But while those around him, including Assad's cousin Rami Makhlouf, acquired great wealth, ordinary Syrians saw few benefits.

He also maintained the grip on power held by his family and Alawite sect in the mainly Sunni Muslim state. His brother Maher commands the Republican Guard and is the second most powerful man in the country while brother-in-law Assef Shawkat is deputy chief-of-staff of the armed forces.

Assad's wife Asma, who grew up in London and worked at an investment bank, helped him try to project a softer, liberal and modern image to the outside world, countering Syria's reputation as a repressive police state.

A Vogue magazine article published in March – and widely criticized for glossing over Syria's poor human rights record, jailing of political dissidents and absence of free elections – painted a picture of a "wildly democratic" Assad household.

"We all vote on what we want, and where," it quoted Asma as saying, adding that a chandelier made of cut-up comic books was chosen by the children. "They outvoted us three to two on that."