Tajikistan's President seems certain to strengthen his power by referendum on Sunday in a country bordering Afghanistan and seen in Russia as a front line in the battle against Islamist militants and drug traffickers from Afghanistan.

Imomali Rakhmon seeks a constitutional blanket ban on religious parties after a court shutdown of the opposition Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) last year. Some of its leaders face life in jail on charges of plotting a coup.

IRPT was a successor of the Islamist wing of an opposition bloc which fought Rakhmon's government in a bloody civil war in the 1990s. The crackdown on the party marked a decisive break from the power-sharing agreement which ended the war.

Mostly Muslim Tajikistan is the poorest former Soviet republic. Russia maintains a base in the country in support of the government and dominates a force guarding the 1,300 km long border with Afghanistan.

Tajikistan has never held an election judged free and fair by Western observers. Rakhmon loyalists dominated the latest vote in March 2015 while the Islamists failed to clear a five-percent threshold needed to win seats for a party.

Stirrings of conflict

Constitutional amendments drafted by a loyal parliament, and reflecting autocratic rule in neighboring Central Asian states, will allow Rakhmon, in power since 1994, to run for an unlimited number of presidential terms. Without them, his current term ending in 2020 would be the last one.

The legal reform will also lower the minimum age for presidential candidates, allowing Rakhmon's elder son Rustam, who runs the state financial control agency, to run for office if he chooses to do so. Ozoda, one of the president's seven daughters, is his chief of staff.

The peace in the 1990s civil war was hard won and any signs it could unravel would be viewed with deep concern in Moscow.

A former member of the armed opposition movement, General Abdukhalim Nazarzoda, was killed last September in a gunfight with government forces after a failed attempt to seize power from Rakhmon.

Political tensions have intensified against a backdrop of deepening economic crisis triggered largely by a recession in Russia, where hundreds of thousands of Tajiks work in order to provide for their families at home.

Many of them have since had to return home either because they lost their jobs or because their wages were no longer sufficient following the Russian ruble's devaluation.

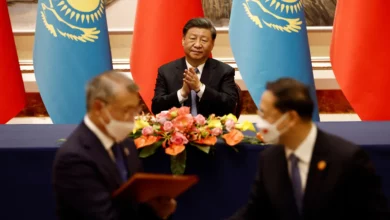

There have been no notable public protests against Rakhmon. But the government of oil exporter Kazakhstan, the richest country in the region, has faced a wave of rallies amid public discontent over worsening living standards.