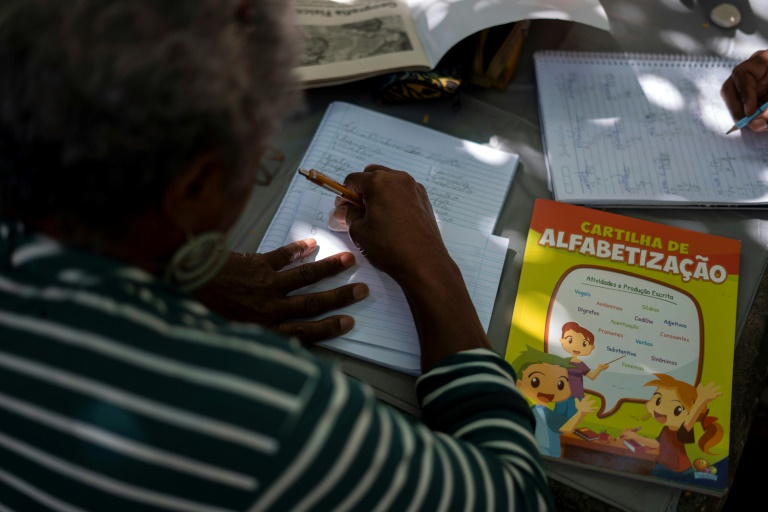

A firm believer in the idea of “better late than never,” 86-year-old Edna Pinheiro practices reading with a tutor in a Rio de Janeiro square — one of hundreds taking advantage of free outdoor classes.

“I’m going to study while I can because little by little, we lose our sight and we turn into old ladies who can’t read or do anything,” says Pinheiro, who could barely read or write before joining the Adopt a Student project.

The brainchild of engineer Silverio Moron, Adopt a Student has helped nearly 300 people of all ages to brush up their skills in subjects including math, physics, English and Brazil’s official language Portuguese since its launch last year.

A former tutor for private school students, the 64-year-old Moron says he wanted to share his knowledge with those who could not afford to pay for classes.

So he placed a sign on a cement table in a public square that said: “I answer questions on math and physics.”

Moron had to wait several days before he got his first student, but soon dozens were showing up looking for help.

AFP / MAURO PIMENTEL Brazilian engineer Silverio Moron (C) is the founder of the Adopt a Student initiative, which offer free classes in Rio’s public squares

AFP / MAURO PIMENTEL Brazilian engineer Silverio Moron (C) is the founder of the Adopt a Student initiative, which offer free classes in Rio’s public squaresA team of volunteer teachers now tutors groups of no more than three people at a time in several neighborhoods.

“I know that we are still a drop in the ocean,” Moron tells AFP.

“That drop in the ocean may one day become a tsunami of education.”

Getting results

There is a huge need.

Brazil’s woeful school system is blamed in part for the country’s high rates of violence and unemployment.

More than 11 million people over the age of 15 are illiterate, according to the national statistics agency.

AFP / MAURO PIMENTEL Retired journalist Heloisa Sefton, 60, teaches Portuguese to a group of people in the Mauro Duarte square in Rio’s Botafogo neighborhood

AFP / MAURO PIMENTEL Retired journalist Heloisa Sefton, 60, teaches Portuguese to a group of people in the Mauro Duarte square in Rio’s Botafogo neighborhoodThe World Bank estimates it would take Brazilian 15-year-olds 75 years to reach the OECD average score in math, and more than 260 years in reading.

Moron’s tutorials are making a difference.

When left-handed student Camila Ribeiro, 11, broke her left arm, her grades plummeted, her mother Marta tells AFP.

After a month of tutoring in Portuguese and math, though, her daughter has “improved a lot,” she says.

For Maria do Jesus Rangel, 77, the tutorials were a chance to get the education she was denied as a child.

“In my era, parents didn’t send their kids to school,” says Jesus as she finishes up one of her three weekly literacy classes.

“It was very difficult for those working in the countryside. The mentality was that a woman should look after the home and the men work the land.

“I have two children who have graduated (from university). Now, it’s my turn,” she adds proudly.

Moron is reluctant to discuss the politics of education and the recent wave of protests involving students and teachers angry over the education funding cuts planned by President Jair Bolsonaro’s government.

AFP / MAURO PIMENTEL Math is one of the subjects being taught in Adopt A Student classes

AFP / MAURO PIMENTEL Math is one of the subjects being taught in Adopt A Student classes“The aim of the project has nothing to do with the government, nor with the one before it,” Moron says.

It is not about “questioning” public power but “helping” it, he says, though he acknowledges teachers in the public system should earn higher salaries.

Moron hopes that Adopt a Student will spread to public squares across the city.

“For that, we need the support of residents in each neighborhood, for them to come out of their homes into the squares to share their knowledge,” he says.

Chance to learn

AFP / MAURO PIMENTEL Edna Pinheiro, 86, only went to school for six years — now, she is improving her reading and writing skills

AFP / MAURO PIMENTEL Edna Pinheiro, 86, only went to school for six years — now, she is improving her reading and writing skillsPinheiro slowly reads out loud, her finger pointing at the words she has just written in her notebook.

“From now on, you can read all these names for yourself,” she says, as her tutor listens.

Recalling her six years of schooling, Pinheiro says she used to get home to find “a sack of coffee waiting for me to carry to the field where I cut cane, corn and hoed dirt.”

“By the time I returned home, I was tired — I showered and went to bed. The next day I went back to school, but I didn’t learn anything,” she says.

Now, for the first time in her life, she says she is “learning something.”