In 2003, the United States invaded Iraq and captured its leader, Saddam Hussein. More than two decades later, US special forces captured former Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro in Caracas — another despot presiding over billions of barrels of crude oil.

Despite that blunt parallel, Venezuela presents a different case in many ways: There is no war, no American troops on the ground, not to mention entirely different social and political systems. But the post-invasion fallout in Iraq offers valuable lessons for oil companies considering entering Venezuela.

According to analysts, it will likely take many years before oil majors decide to make substantial investments in Venezuela, not least because they are expected to navigate unpredictable and potentially volatile security challenges.

For these firms, “it’s really going to be a very, very difficult mountain to climb,” said Bill Farren-Price, a senior research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. “Efforts to rebuild oil industries — even in major producers like Iraq and Venezuela — take years.”

What happened in Iraq?

Several days after the United States and its allies invaded Iraq, then-Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz told a congressional committee that the country’s vast oil reserves could cover the costs of Iraq’s reconstruction.

That did not come to pass.

“The Bush administration definitely thought that the US itself, Iraq and the oil industry would see the economic benefits (from Iraqi oil) much more quickly than it was realized,” Mohamad Bazzi, director of the Center for Near Eastern Studies at New York University, told CNN.

Iraq’s oil industry had been nationalized and closed off from Western oil companies since the 1970s.

Soon after its invasion, the United States disbanded the Iraqi armed forces and purged the Iraqi civil service of thousands of members of Hussein’s ruling Baath Party. This placed government departments — including its oil ministry — under temporary US control.

An interim Iraqi government took back authority. the following year, but it wasn’t until around 2009, analysts told CNN, that officials began offering contracts to foreign oil companies.

Even then, the type of contracts the government offered were unattractive to these firms, according to Raad Alkadiri, managing partner of 3TEN32 Associates, a political risk consultancy advising oil companies. Alkadiri worked as an advisor to UK diplomats in Iraq between 2003 and 2007. (The UK was Washington’s biggest coalition partner in the war).

He said the contracts effectively invited foreign firms into Iraq as contractors rather than allowing them ownership rights over the oil reserves. Only very recently has the Iraqi government began offering more attractive terms, he added.

“Some of the promise and the ambition that ran through the minds of oil companies prior to the invasion… were disabused very quickly when the Iraqis sort of introduced their own system,” Alkadiri told CNN.

It wasn’t just the economics making foreign oil companies wary. The security situation inside Iraq rapidly deteriorated after the invasion, aided in large part by a power vacuum.

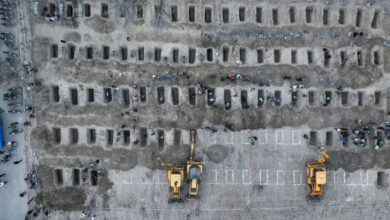

“So for years after the US invasion, there was looting of oil, there were attacks and sabotage of the existing oil infrastructure, and of course, there was the unfolding insurgency and then civil war in Iraq itself,” said Bazzi at NYU.

Lessons for Venezuela

It is too early to say how the security situation inside Venezuela will unfold.

But the Trump administration has kept remnants of the Maduro regime in place, unlike in post-invasion Iraq, said Carlos Solar, senior research fellow of Latin American Security at the Royal United Services Institute.

According to Solar, there are armed groups in Venezuela that could create a “chaotic security scenario” that would be “way less controllable than it is to negotiate with Delcy Rodríguez,” the country’s acting president and Maduro’s former vice president and energy minister.

Venezuela is a “highly militarized country,” he told CNN, with four main armed groups: the Venezuelan army; organized criminal gangs; Colombian guerilla groups; and colectivos, paramilitary groups loyal to Maduro enforcing rule in many neighborhoods.

Rather than deploy US troops, the Trump administration is preparing to use private military contractors to protect oil and energy assets in Venezuela, two sources familiar with the plans told CNN. During the Iraq War, the United States spent billions on private security, logistics and reconstruction contractors, though they were marred in controversies such as the killing of Iraqi civilians.

“The security picture is really a serious one,” said Amy Myers Jaffe, director of the Energy, Climate Justice and Sustainability Lab at New York University. Currently, she said, there are too many uncertainties for oil majors to justify spending vast sums of money to meaningfully restart operations in Venezuela.

“Is the current government… staying in power? Are they going to have elections? Will those elections be contested?” she said. “Does everybody agree that this oil company or that oil company should be continuing, or adding, or coming in with new operations?”

“The lesson of Iraq is that it’s not really about how much oil is there — it’s about what’s going to happen on the ground,” she added.

CNN’s Isabelle Khurshudyan, Zachary Cohen and Kylie Atwood contributed reporting.