Lviv, Ukraine — When there was a knock on Yulia Olkhovska’s front door at 5:30 a.m., she knew who would be waiting for her in the pre-dawn darkness outside. But she was still terrified.

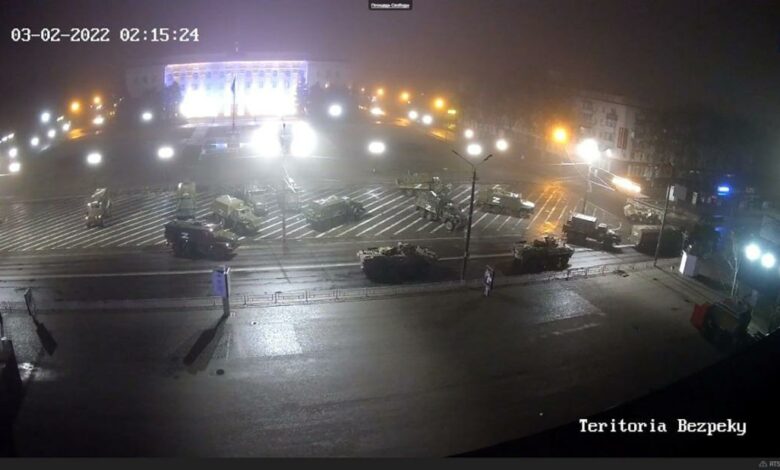

Ever since Russia invaded Ukraine, rolling tanks into several small cities in the country’s southeast, including her hometown Melitopol, there had been a steady, grim drumbeat of disappearances.

Journalists like herself, as well as activists, politicians, public figures and residents in Russian-occupied areas were being picked up off the street and snatched from their homes. She had conferred with her husband in hushed tones about what to do if they came for her; the pair decided they would try to remain calm.

So when five armed men in military uniform turned up at her house in the suburbs of Melitopol on March 21, she took a deep breath and let them in. After carrying out a room-by-room search, startling their sleeping teenage daughter and four cats, the Russians told Olkhovska to come with them.

The reporter, who works for the newspaper Melitopolski Vedomosti (MV), was loaded into a minivan and driven quickly to her own empty newsroom, which had been seized by Russian forces. In a surreal scene, she said she was sat down in her editor’s office and interrogated for five hours.

“They said to me, something like, ‘A new life is beginning here, and you’ll probably be interested to take part in building this new life. Not to sit somewhere on the sidelines, but be at the center. We’re giving you an opportunity to work. We need objective people, who can write, to document this new life,'” Olkhovska told CNN in a recent phone call.

When the journalist made clear she wouldn’t collaborate, the Russians — one of whom had introduced himself as a member of the new civil-military administration — replied coolly. “They said they understood that I was scared, a little confused, and they didn’t demand an immediate answer from me. They offered to let me think a little more,” she recalled.

A week after her release, Olkhovska is still waiting anxiously for another knock on her door. After she and several of her colleagues at MV — among the most prominent news outlets in the city of 150,000 people — were kidnapped, the general director of the media holding decided to halt publication in print and online. It’s a move that other major media organizations in the region have been forced to make, as they weigh the impossible choice between safeguarding their people and reporting on the threat that they, and other citizens, now face. Access to some websites has simply been blocked.

Their coverage has been swapped for Russian propaganda, streamed from local TV towers, on radio stations and Telegram channels. After the kidnapping of Melitopol’s mayor on March 11, the pro-Russia politician who replaced him, Galina Danilchenko, broadcast this statement: “Our main task is to adjust all the mechanisms to the new reality in order to start living in a new way as soon as possible.”

The Orwellian message was among the first, chilling signs of the next phase in Russia’s war: Occupation. It has been characterized by abducting local officials, appointing sham councils and enlisting collaborators to create a climate of chaos and fear. That post-invasion playbook, which was used in 2014 by Russian President Vladimir Putin to annex Crimea, and in Donetsk and Luhansk — two Ukrainian regions where pro-Russian separatists terrorized parts of the local population and set up puppet regimes — is not working as well this time around.

‘I’m scared just to go outside’

Families are often denied any information about the fate of those being held. And most are too terrified to speak out about the disappearance of their relatives, for fear that it could trigger a backlash against themselves or their loved ones.

“Those who are in occupied territories, they [the Russians] try to scare them with this terror against local active people, local officials, councillors and mayors. It’s a campaign of terror, trying to suppress people who move against occupation,” Ukrainian lawmaker Oleksiy Honcharenko, a member of Dmitry’s European Solidarity party, said in a call with CNN about his colleague’s detention.

On the evening of Dmitry’s disappearance, Ukraine’s Deputy Prime Minister Iryna Vereshchuk said in a televised address that Russians involved in the kidnapping and torture of Ukrainians would be held accountable for their crimes.

“In recent days, I have received many messages from people who managed to escape from the captivity of the occupiers. They report mass cases of torture of prisoners. I would like to emphasize publicly that we will find every Russian serviceman and every accomplice who commit war crimes and bring them to justice in The Hague tribunal and other courts,” she said.

“Do not think that we do not know your last names.”

Interrogations, beatings and threats

In Lviv’s international media center, housed in a converted craft beer bar, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) and Ukraine’s Institute of Mass Information are documenting cases of arbitrary detention to submit to the International Criminal Court. They recently published the chilling anonymous account of a Ukrainian journalist working for Radio France, who says he was tortured by Russian soldiers with a knife and electricity, beaten with steel bars and deprived of food.

“Being kidnapped, tortured for showing what the situation is in de-facto occupied territories of Ukraine, like Kherson, and other areas. It’s just Russian freedom of the press 101. It’s an extension of what they already do in Russia,” RSF’s local coordinator Alexander Query, who is also a journalist for the Kyiv Independent, told CNN in an interview at the center.

Oleh Baturin, a journalist from the Kherson region, was released on March 20, eight days after going missing. Speaking to CNN from his home, the Novyi Den newspaper reporter said that he was abducted at a bus station in the port city of Kakhovka where he had promised to meet a trusted activist source. The source, a former Ukrainian soldier who had been involved in local protests against the occupation, had reached out to him — after posting on Telegram that he was worried the Russians were searching for him — and said he wanted to meet.

“Interrogations, beatings, threats lasted for about two hours on the first day … Then there was purely psychological pressure. And interrogations every day.”

Oleh Baturin

Baturin agreed, but something about the call didn’t feel quite right. “I felt anxious that day. I shared that anxiety with my family … and when I left home, I told them I was going there, just to meet this person. I would be back in 20 minutes,” he recalled.

At the station, he said he was swarmed by a group of Russians, who dragged him into a minibus and took him to a series of different regional administrative buildings now under Russian control. “Interrogations, beatings, threats lasted for about two hours on the first day,” said Baturin, who described being isolated in a cell and chained to a radiator. “Then there was purely psychological pressure. And interrogations every day.”

During the interrogations, Baturin said that the Russians repeatedly questioned him about his sources: Who are the most prominent activists in the Kherson region? What were the names of the people organizing pro-Ukrainian rallies? After he was released, the Russians apparently having lost interest in him, Baturin learned that his source had gone missing the same day he himself was abducted. He still hasn’t surfaced.

Viktoria Roshchina, a journalist with Hromadske Radio station who also disappeared on March 12, from the occupied seaside city of Berdyansk, was freed 10 days later after she says she was forced to record a video saying the Russian soldiers “saved her life” and that she was “treated well.”

Creating an alternate reality

The persecution of journalists like Baturin is a key part of Russia’s occupation blueprint, according to Sergiy Tomilenko, president of Ukraine’s National Union of Journalists, who has documented cases like his since Putin’s invasion of Crimea eight years ago.

“Their strategic goal is to create an alternate reality,” Tomilenko said. “Russian occupiers propose to local journalists, media, to be their protagonists. In this stage, after tanks, after fighting and occupation, they work to try to involve journalists in their campaign.”

“But many don’t want to collaborate, and so the second part of their objective is to silence, to stop critical media coverage.”

That carrot and stick approach was used on Svitlana Zalizetska, director of Melitopol’s main newspaper, Holovna Gazeta Melitopolya, and RIA-Melitopol news website. Her 75-year-old father was abducted by Russians on March 23, after she refused to report in support of the occupation.

Just hours before Melitopol’s mayor, Ivan Fedorov, was abducted, Zalizetska said she was picked up from her home and taken to an industrial plant for a meeting with the woman that Russia installed in his stead. “Galina Danilchenko had a personal conversation with me. She told me about how I should work for them, cooperate with them, what career awaits me in Moscow and so on. And she said that the commandant wants to meet me in person,” Zalizetska told CNN.

“I’m afraid for my life, and I’m scared just to go outside.”

Oksana Afanasyeva

“I replied that, ‘I did not need any commandant, because, I’ll tell you right now: There won’t be any cooperation with you. I love Ukraine and I want to live in my native Ukraine. And not in the Rushka [a derogatory name for Russia].'”

After the experience, Zalizetska packed her bags and left her home, staying in several apartments before fleeing the city. Days later, she said she got a call from the Russians to tell her that they had her father and wanted her “nearby.” She refused and happily, three days later, he was released.

Zalizetska is adamant about carrying on her coverage of life under Russian occupation in Melitopol to document kidnappings and detentions, like that of her own father. But many more have stopped, terrified for their lives and the safety of their families.

After 20 years working as a journalist, Olkhovska, the Melitopolski Vedomosti reporter, is taking a hiatus from reporting, worried that the Russians will come back for her.

Sitting at home in her living room, she is horrified at the pro-Kremlin propaganda now playing on her TV — the 32 channels she once received have been reduced to fewer than 10. Watching life through Russia’s looking glass, she knows with every fiber of her being that she couldn’t work for them, helping to spread lies about life under occupation.

“I think they’ll probably come again. But so far, thank God, they haven’t. I hope they have already forgotten about me,” Olkhovska said.

Oleksandra Ochman contributed to this report.