As Egypt lurches between political chaos, repeated street violence and economic uncertainty under the stewardship of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, the International Crisis Group has taken upon itself the unenviable task of trying to work out what exactly SCAF is thinking.

The Brussels-based think tank’s 24-page report, “Lost in Transition: The world according to Egypt’s SCAF,” is an attempt to identify why SCAF has behaved like it has during Egypt’s 14-month transition. The report was released on 24 April.

SCAF’s performance, ICG says, has at times been “head-scratching” and understanding the Egyptian military’s mindset “requires modesty in reaching conclusions.”

Central to SCAF’s handling of the transition is its belief that it protected the revolution, and that the revolution’s aims were realized once Mubarak stepped down, the report says.

It is for this reason that it has responded with at times violent hostility to protests after 11 February 2011, particularly as it considers itself the “sole actor possessing the experience, maturity and wisdom necessary to protect the country from domestic and external threats. In contrast, virtually all political parties are regarded with scorn, self-centered in their demands, narrow-minded in their behavior.”

The Muslim Brotherhood — large and organized — is an “exception of sorts” to this. The report suggests that SCAF grudgingly respects the Brotherhood as power player in Egyptian politics that survived decades of oppression.

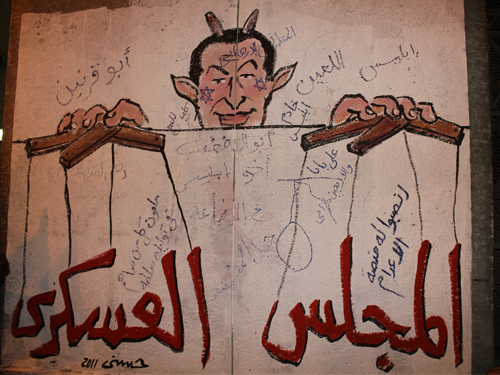

The relationship has not always been one of respect, however, and ICG suggests SCAF has been “playing secularists against Islamists and Islamists against secularists to the alienation of both.”

The first significant clash between SCAF and Islamists occurred in October 2011, when SCAF put forward Deputy Prime Minister Ali al-Selmy’s supra-constitutional principles, which would have given the ruling generals the right to appoint most of the members of the committee writing the constitution.

The Muslim Brotherhood responded by organizing a mass rally in Tahrir Square. There has been much speculation about the exact nature of the relationship between SCAF and the Brotherhood, with talk of manufactured public spats to conceal private secret deals.

Relations are still tense with the Brotherhood, which is organizing weekly rallies in Tahrir Square and calling on the military council to dissolve the Cabinet.

The ICG says, “Neither the SCAF nor the Muslim Brotherhood wanted it to come to this.”

“For the two, the clash is premature. Both would have benefited from a compromise agreement, safeguarding essential military prerogatives while setting the country on a clear path toward full civilian rule, allowing the Islamists to govern but ensuring it happens gradually and inclusively, consistent with the Muslim Brotherhood’s own fear of grabbing too much too soon,” it says.

SCAF’s confused, prevaricating treatment of the transition process has led some critics to allege that it is working solely to protect its own interests rather than those of the country, by dividing and bamboozling political groups.

The ICG suggests that SCAF genuinely believes it is working for Egypt’s good, quoting a retired army general as saying that “the SCAF works under the assumption that it is the only party that truly cares about Egypt’s interests. The parties and other groups have merely pounced on the political spoils.”

“The conflation of its role as protector of stability with the national interest has led SCAF to view criticism of its performance as attacks against the country’s last standing institution — and, it follows, as the work of those who wish Egypt ill. …Understanding this outlook is critical to understanding why the SCAF acts as it does, at times seemingly against its own interest,” the report reads.

In the run up to presidential elections, ICG says, SCAF must “take a step back and, with the full range of political actors, agree on principles of a genuine and safe political transition.”