On one end of the concrete wall blocking Qasr al-Aini Street stands a small grocery store with a red façade. Like with other shops across downtown Cairo sales have gone down due to the stifling traffic brought about by the concrete barriers and occasional skirmishes over the past two years. But unlike the rest, more pedestrians flock into the shop. Lucky for downtown dwellers, the store has two doors: one on each side of the wall, and the middle-aged grocer sits on any given day occasionally greeting those who walk through as he carries out his work.

Downtown Cairo is not as bleak as it may seem. Residents and shop owners have been finding creative ways to overcome the challenges and lead a normal life. And so have artists.

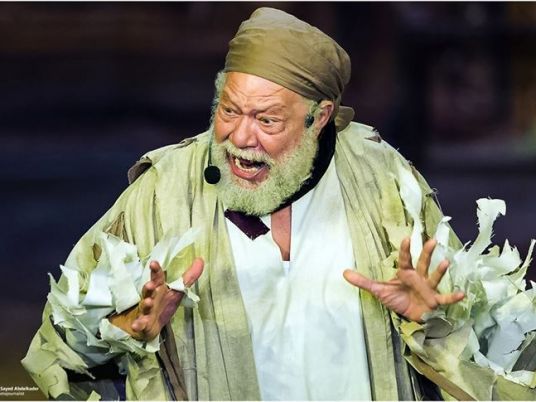

With funding and affordable rehearsal spaces for performing arts continuing to dwindle, and opportunities between the state’s rigid yet unclear cultural policies and commercial theater leaving little room for experimentation, three multidisciplinary arts festivals are proposing alternative models to bring performing arts to the forefront.

By the beginning of April, the Second Downtown Contemporary Arts Festival (D-CAF), Hal Badeel and Al-Fan Midan are set to raise the curtain on their exciting programs, which cater to both the local community and hopefully those who have been avoiding the neighborhood altogether.

D-CAF, although conceived prior to the 18 days, kicked off its zero edition last April with two weeks of cutting-edge plays, dance performances, music concerts, an exhibition on censorship of artworks and a film program.

Partly sponsored by Al-Ismaelia for Real Estate Investments, which has purchased several buildings in downtown Cairo over the past few years as part of its urban regeneration project, one of D-CAF’s main goals has been to “revive the neighborhood, and make it once again a place where people from all roads of life meet,” explains Kareem el-Shafei, chief executive officer of the Ismaelia consortium. For Shafei, art activities are one way to do this.

Last year, several performances and screenings were held at key downtown sites from the Radio Theater to the bustling Boursa pedestrian area. This April, the festival’s artistic director, Ahmed El Attar, has expanded the program over an entire month, with more interactive acts — from a feature where passers-by can write anything they want on a gadget and have it projected live onto a shop front on Adly Street, to a live performance in a shop window overlooking Mahmoud Basiony Street with which pedestrians become involuntarily entangled.

Attar is a leading performer and founder of Studio Emad Eddin, which has offered, for almost a decade now, rehearsal, training and residency spaces to independent artists and troupes from Egypt and the Middle East. For him, another key function of D-CAF is to highlight some of the most experimental performances from Egypt and abroad, while also linking performance artists across the continents.

“Festivals are different from showcases,” says Attar. They need to present “a multitude of offers within a given time.” The problem with many of the state’s existing festivals, he explains, is that they lack a clear artistic vision and are often used as propaganda for a particular regime.

D-CAF hopes to address these problems. And so does the new Hal Badeel, which will kick off next week only a few blocks away from some of D-CAF’s numerous venues.

But the alternative solution, as the name of the festival translates, also proposes a crowd-funding model of sorts. Hal Badeel is exhibition manager Mido Sadek and theater practitioner Saber al-Sayed’s response to the closing of downtown’s Rawabet Theater, a major hub for alternative performing artists, earlier this year due to funding challenges.

For three weeks, a selection of plays, stand-up comedy shows, dance performances and experimental films by upcoming filmmakers will play. Everyone involved, from the organizers and artists to the technicians and carpenters, are volunteering, bringing in their own materials and devoting their time.

“We did not want the performing arts scene to be at the mercy of funding organizations,” explains Sadek. “Whenever their priorities change, so does the artists’ ability to show their work and people’s access to them.”

Their idea is to take up spaces rarely used for performing arts and turn them into well-functioning pseudo theaters that engage local communities, explains Sadek. For their first edition, they have managed to take up the Townhouse Gallery's Factory Space, which has a regular visual arts exhibition program, and convert it into a full-fledged theater.

The floors, walls and ceiling have been plastered to overcome problems of echo and create a stage. And leveled benches have been set up for the audience. All the events are free of charge, to be as accessible as possible.

For their next issue, they want to repeat the experiment in a different location, possibly a dilapidated building or an empty piece of land being used as a garbage collection point. They would take it, clean it and once again turn it into a space to host the itinerant festival.

But, as with others, finding sustainable funding might be a challenge. Attar admits that the zero edition of D-CAF incurred losses of LE400,000, despite having revenue from tickets and some corporate sponsorship.

Ideally, a festival’s budget needs to be divided between the state, private funders and foundations, and ticket revenue to be sustainable, says Attar. And as festivals succeed in their offerings to the public, private companies and the state gradually become more interested in contributing.

For him, the most important thing is having a vision and determination. Once that is cleared out, you accept some losses and work constantly on minimizing them to remain operational.

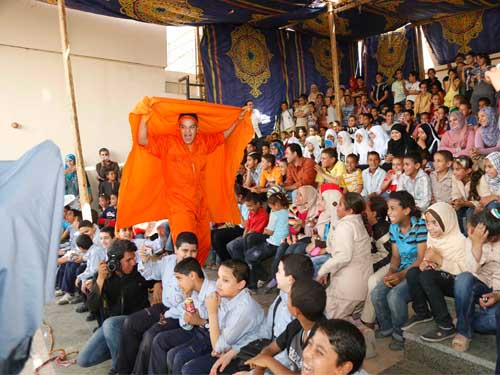

This has proven successful to some extent with the monthly street festival Al-Fan Midan. Since April 2011, a number of cultural organizations have come together to host a show of music and performances, first in downtown’s Abdeen Square on the first Saturday of the month, and over time, to the different governorates of Egypt.

Like with Hal Badeel, all performances at Al-Fan Midan are free, and everyone involved is a volunteer. Only a few times have the organizers called out for donations to keep their program — which ranges from experimental music and plays to Egyptian folk arts — going. And under the leadership of former Culture Minister Emad Abu Ghazi, they have managed to obtain partial funding from the ministry, mostly to cover equipment rental.

Two years into the project, Al-Fan Midan is considering seeking alternative sources of funding, says theater director and organizer Abir Ali. They are, however, debating which organizations or corporations to reach out to, if any, while maintaining the festival’s highly accessible nature and independence.

But another solution they are thinking of is institutionalizing themselves. “If we have a legal structure, we can charge symbolic tickets occasionally and hold fundraising events,” explains Ali.

They are also working in parallel on putting together a law that governs the work of nonprofit cultural organizations.

“This would allow us to generate some revenue [to sustain our program] without being taxed like entertainment facilities, which we are not,” she adds.

They hope to submit a proposal to the government soon that would also include providing tax exemptions as an incentive to companies that support cultural institutions.

So despite the many difficulties on the local arts scene, a multitude of possibilities arise for both artists and audiences in downtown Cairo and hopefully other neighborhoods and villages across Egypt.

“We need to take a chance [on art] and see,” says Attar. “Otherwise we’ll all be missing a big part of life.”

Hal Badeel kicks off on 24 March. You can check their program here.

D-CAF kicks off in Cairo on 1 April. You can check their program here.

Al-Fan Midan takes place on 6 April. There program can be found here.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.