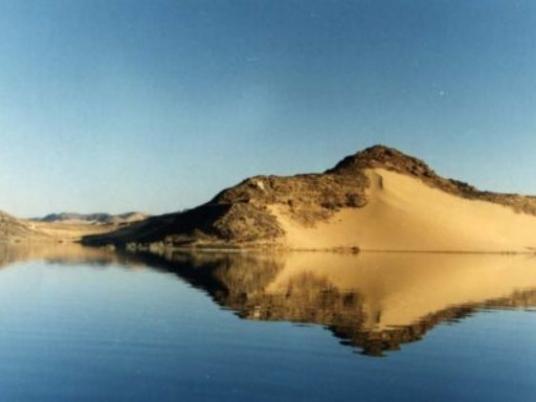

Among the amazing landscapes the country possesses, the most precious are undoubtedly the seashores on the North Coast and the Red Sea, as well as the desert. Countless sites in these areas are unique and rare wonders of nature, and require special care and protection.

The Tourism Ministry has a plan for how to use these natural reserves to their full potential and develop environmental tourism. But there is a lot to do, and there are many obstacles that handicap the project.

Tourists are now eager to delve into rough natural surroundings and indulge in wildlife adventures, to get away from their urban lifestyles — and, if managed properly, they can find all of this in Egypt.

“Eco-tourism is booming,” says Mahmoud al-Kaissouny, environmental adviser to the Tourism Ministry. “And it is on its way to representing half of international tourism.”

The country’s 2,600 kilometers of beaches offer countless diving spots, including underwater landmarks and caves on the North Coast. The Red Sea is considered one of the top 10 diving destinations worldwide. The desert includes areas of unique geological significance, as well as rare natural rock formations.

These areas need to be protected, and since the 1980s, 30 areas have been declared national parks, most of them located in the desert. In the early 1990s, the Environment Ministry — led at the time by Nadia Makram Ebeid — laid out a plan to declare 40 areas as natural reserves by the year 2017.

But new discoveries were made, and the list lengthened to include 44 protected areas.

“Gebel Kamil, which is very rich in remnants of meteorites, was the last area declared a natural reserve,” says Kaissouny, referring to an area located in the southeast of Gilf al-Kebir, in the Western Desert.

Among the most important protected areas, in terms of biodiversity, are Wadi al-Gamal, Gebel Elba and Wadi Allaqi.

Wadi al-Hitan, located in the Wadi al-Rayan natural reserve, is considered one of the most amazing archaeological spots in the world. According to a UNESCO report, Wadi al-Hitan’s unique whale fossils demonstrate that this type of whale’s ancestor was a land-based animal. This discovery put Wadi al-Hitan on the protected areas map.

But despite their importance, most protected areas have been extremely neglected for years, if not decades.

“After Nadia Makram Ebeid’s term as minister, there was a growing disinterest for Egypt’s national parks, which slowly degraded, Wadi al-Rayan being the most prominent example of this decay,” Kaissouny says. “If you go there today, you will not be able to enter. It is full of garbage and completely degraded — it is very sad.”

The Italian government designated and funded this natural reserve, and even though Egypt was not able to maintain it, it is now willing to reinvest and rejuvenate the reserve.

The government’s plan

The target of the Tourism Ministry, together with the Environment Ministry, is to upgrade and renovate already existing natural reserves, to announce new protected areas, and to use them for economic and touristic purposes.

“This project aims to allow tourism investments within the protected areas of Egypt by loosening the restrictions on these protectorates, a little,” Tourism Minister Hesham Zaazou explains.

He suggests that building codes could be adjusted, such as the law that prevents building on more than 10 percent of protected areas’ land.

“This could be changed to 20 percent, provided that the infrastructure to be built follows a specific set of requirements that ensures the safety and protection of these areas,” Zaazou says.

Not everyone, however, is as enthusiastic as the minister about these plans.

“We do not need to build more,” says Usama Ghazali, former head ranger of Gebel Elba Protectorate.

He believes there is a pressing need to come up with better management strategies.

“The ministerial plan is basically to build more within the protected areas. This is not what we need,” he says. “What we need is more services and facilities that respect the environment.”

There are no laws that govern land use, and none that manage diving centers or other facilities — and most of the time they are not compliant with environmental protection rules.

Ghazali argues that decision makers need to be in the field and understand what the environment and the people living within it need.

“This is very different than what the people sitting at their desks in Cairo want,” he asserts.

He believes that in order to reach an understanding on how to upgrade the protected areas, governing entities and local people need to compromise to help preserve the environment and people’s livelihoods.

In addition, there is a huge obstacle facing this project that is crippling the plans of the ministry.

“In the last 50 years, presidential decrees were issued, and these decrees limited the use of Egyptian land, including protected areas,” Kaissouny says. “Tourism has the freedom to use 6 percent of Egyptian lands.”

Many protected areas require up to 27 permits within 25 days just to access them.

For instance, a group traveling from 6th of October to the Dakhla Oasis, must obtain numerous permits, and then, on the way, they will pass about 18 checkpoints that must certify their permits’ validity. The procedure can be very hectic, and an eight-hour trip to the oasis may take 14 hours.

This makes it difficult to access natural reserves, and these procedures limit tourism in the area.

“The area of Gebel Elba necessitates many permits to acquire the right of entry, and it makes it very hard and frustrating to get there,” Ghazali complains.

Kaissouny says these decrees were issued based on problems that no longer exist, and that they are now useless.

“We are not in a state of war; we do not need all these limitations,” Kaissouny says.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.