VENICE — In the tourist Mecca of Saint Mark’s Square in Venice, the Doge’s Palace is currently holding an exhibition called “Venice and Egypt.” The publicity material on the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia website entices the visitor with “the thousand-year old relationship between Venice and Egypt narrated for the first time ever.” Viewers will experience “a cultural affair that is therefore complex and multi-faceted, spoken of in an exhibition that will surprise the audience by the findings of the research conducted and by the 300 exceptional works that were collected for this occasion.”

What this dramatic introduction fails to reveal is how the image of Egypt in this exhibition is nothing but that — an image — and these imaginations aren’t quantified or qualified anywhere within this sprawling trove of Egyptian treasures, trinkets, coins and maps.

“Venice and Egypt” is held upstairs in the Hall of Scrutiny, a resplendent — albeit dark and glacial — hall. The show consists of a series of objects that look as if they were collected for having any relation to the region. These objects are meant to represent a relationship beginning in the classical age and ending with the opening of the Suez Canal. We see paintings depicting Moses, the Pharaohs, Cleopatra, Marc Antony and Saint Mark, and specimens that display commerce between the two regions, like coins, maps, manuscripts, medals, and gifts exchanged. A slideshow of paintings sits next to a map, next to a painting of Cleopatra’s banquet, next to the gifts of an amphora and urn, next to a beaded sarcophagus, next to a display of Venetian-to-Arabic trading manuals of varying degrees of accuracy. There is very little, if any, historical information and the things of historical value are placed next to BBC docudramas that praise the triumphs of a generation of explorers who looted the rest of the world without consequence. In the Hall of Scrutiny, the viewer approaches an inscrutable Egypt made of the stuff of legends, and if put to the smallest amount of scrutiny the exhibition falls apart as a complete sham, not only of the relationship between Venice and Egypt, but of any realistic depiction of the latter.

The collection of paintings displayed includes some of the superstars of the Renaissance Venetian art scene. It includes Giorgione’s “Moses Undergoing Trial by Fire,” Pietro Paoletti’s “Death of the Firstborn in Egypt,” Titian’s “The Drowning of the Pharoah's Host in the Red Sea” and “Joseph and the Wife of Potiphar" by Tintorreto. The subject matter varies by era — religious paintings of the 16th century are replaced by the picturesque and grandiose of 18th century artists Giandomenico Tiepolo and Giovanni Battista Piranesi.

In “The Passage of the Red Sea,” convulsed forms attempt to part the Red Sea, masses of flesh writhing in the tumultuous waters. In “Death of the Firstborn in Egypt,” we see a depiction of moral degradation during the time of the Pharaohs. Both the paintings represent Biblical stories. The three-meter “Death of the Firstborn in Egypt,” however, is famous for its attention to archaeological detail to such an extent that scholars have speculated that Paoletti may have had contact with the great decipherers of hieroglyphics, Champollion and his crew.

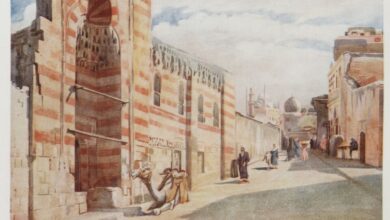

What is barely alluded to in this exhibition is that these works represent an imagined Egypt, and one that was not based on observation. This Egypt was built on European fantasies of the enigmatic East, a motif repeated throughout the art-historical canon, and by now old hat to anyone who has heard the words “orientalism” or “Edward Said” in the same breath. The two artists in this exhibition that could claim some sort of verity in their images — Ippolito Caffi (who visited Egypt in 1843 and shows Old Cairo pastoral scenes) and Giovanni Battista Belzoni (sketches of Egypt and Nubia) — are not distinguished from the morass of myth-making present in all the rest, suggesting that there is no real difference between truth and reality in these paintings. Nor are their works accompanied by any sort of biography explaining their motives for traveling to Egypt, colonialism in the 19th century, or the way that their paintings are being interpreted now, in light of postcolonial discourse and studies of orientalism, which seem completely absent as a frame of reference in the curation of this show. The image it presents is based on whimsy, fancy and falsehood.

In front of the absolutely stunning Nehmeket mummy, a BBC video plays on a continuous loop. “The Adventures of Giovanni Battista Belzoni” (2005) is a dramatized biography of Giambattista Belzoni, the 19th century Italian explorer considered “the father of archaeology,” claiming his responsibility for this find and the tomb at Abu Simbel and for presenting a cache of Egyptian antiquities to the British Museum. If you saw the video, you would think that you had seen it before. It contains one clip that seems to be reproduced in every western Indiana Jones-explorer-narrative-re-enactment: man stands in khaki with crew at the rectangular mouth of tomb, backlit, hammer or some kind of sickle tool in hand, gaping, staring at the bounty they’ve just discovered. As I approached the screen, the robust BBC voice booms proudly, “Belzoni has a claim to being the greatest explorer in the history of Egypt.” The greatest? While Belzoni’s reputation has enjoyed a bit of rehabilitation in recent years, he is generally described in historical accounts as one of the most infamous looters of Egyptian artefacts.

Truthfully, the wilful neglect of recent history in this exhibition is what makes the show so offensive. While the Middle East tries to speak for itself, it faces the burden of historical representation by western colonizers. And rather than attempting to dismantle these stereotypical representations of the region, there appears to be such an investment in the static Egypt: the Egypt of Elizabeth Taylor as Cleopatra, the Egypt of the pharaohs, and the hieroglyphics, and the sensual East: Egypt as western fantasy.

In an interview with Artnowmag, curators Enrico Maria Dal Pozzolo, Rossella Dorigo and Maria Pia Pedani talked about their work. As quoted on the website for the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, “the scientific project [the exhibition] … involved almost 70 specialists including the scientific community, cataloguers and experts involved in analyzing the material.” Considering how little research appears in the room itself, we can only speculate about the planning itself. They said: "This exhibition aims to be a tale." Truer words never spoken. It’s time for Egyptians to tell their own tale.