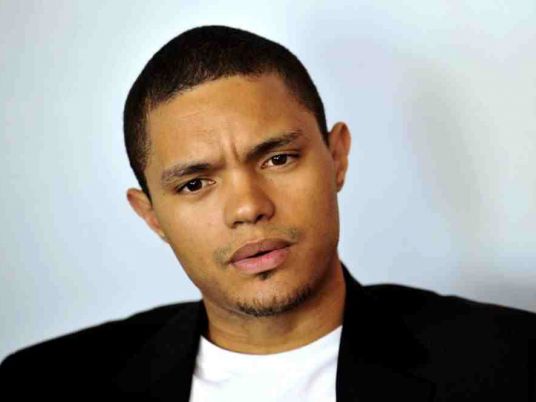

For someone who uses the word "terrified," Trevor Noah looks anything but.

Just days before he takes over the "The Daily Show" anchor chair from Jon Stewart, TV's toughest act to follow, Noah is willing to acknowledge "it isn't easy to reboot and recreate a new show from an old show in just five weeks."

Which he has been obliged to do, stepping in as host on Monday at 11 p.m. EDT on Comedy Central little more than a month after Stewart ended 16 years as the nation's court jester who molded "The Daily Show" in his own savvy image.

Still, Noah looks calm as he greets a reporter in his not-quite-settled-into office at the network's so-called World News Headquarters.

"The joke we have in the building is that I'm the Boy King with a lot of responsibility," he says, "but with a lot of great people who can guide me."

Noah, of course, is the 31-year-old South African comedian who until his ascension few had heard of, apart from a worldwide fan base including 2.6 million Twitter followers who flocked to his shows from Sydney to Dubai … and also, notably, Jon Stewart, who admired his work and reached out several years ago for a meet-and-greet.

That overture led to an invitation to drop by "The Daily Show," which Noah found to be "the most daunting experience I've ever seen: There was an insane amount of work going on."

Noah was eventually signed to make an occasional appearance as a correspondent.

Then, last February, Stewart announced he was leaving.

When Noah began getting feelers about being his replacement, "I asked Jon, `Have you been kicked out?' He said, `No, I'm tired.'"

Whereupon Noah asked him the big question: What was his stance on Noah as his successor?

Stewart's reply, according to Noah: "Who do you think suggested you?"

A month later, he was tapped by Comedy Central.

"Then the whirlwind started," Noah laughs.

Within hours, a handful of Noah's old tweets resurfaced, lousy jokes that targeted women, Jews and Ebola virus victims. A social media firestorm erupted with the press fanning the flames.

"To reduce my views to a handful of jokes that didn't land is not a true reflection of my character, nor my evolution as a comedian," Noah tweeted in response.

"It's not like it didn't affect me, or hurt me," he says now, a lean, baby-faced presence clad in jeans, T-shirt and running shoes. "But I understood it, which helped me get over it."

Defying social-media admonishments, Noah argues that a smattering of dumb tweeted jokes, like anything unearthed from a person's digital past, serves usefully as evidence of what that person may have been and, more importantly, has moved beyond.

"Should we erase our history because someone will judge us by that now, in the present?" poses Noah, and says no. "I think history is a reminder of what not to repeat."

The uproar (including speculation that Noah might be pitched overboard) quickly subsided, but not before the story had been covered to death and, says Noah, too often driven by hearsay.

"It was a beautiful baptism of fire," he says. "What better way to learn the purpose of my new job than to be at the epicenter of many of the problems of how the media covers news?"

Roots of Noah's humor

Certainly, Noah's new job is to quarterback the "Daily Show" truth squad as it lampoons news makers and the media that cover them in the context of the serious business of the comically fake newscast.

"Comedy is a very powerful tool," says Noah. "The truest things are said in jest."

He jests from the standpoint of someone born to a black mother and a white father 10 years before apartheid ended ("I was born a crime," he sums up) whose mother had to walk ahead of him as a toddler, pretending not to know him if she saw the police.

"I come from a crazy place," he says. "When I was 25, my mother was shot in the head by my stepfather, an abusive alcoholic. I was so, so angry. But the first thing she said to me after she came out of the hospital was, `You need to learn to forgive. Then you'll be setting yourself free.'"

He found a certain freedom in comedy, which he pursued, he says, not to vent his spleen, as with many comedians, "but because I made people laugh."

A man of mixed race and a stormy childhood, he saw himself as a perpetual outsider. But he made himself at home globally, including the United States, where he toured comedy clubs and landed TV appearances (including "The Tonight Show with Jay Leno" and "Late Show with David Letterman").

From the beginning, he joked about things that were on his mind, but even when they touched on painful social issues he was never fueled by anger, he insists. Nor is he now.

"I come from a country where everything that happened was impossible! A place where there was a bloodless revolution, where Nelson Mandela, let out of jail after 27 years, made peace with his persecutors. And now I have an almost delusionally optimistic view of America. I see a lot of progress here. I see a lot of hope.

"It's often difficult to see progress when you look at it one day at a time," he muses. "Like with a workout regime: Take a picture today, then take another picture not tomorrow or the next day, but after six or eight weeks. That will show you how far you've come."

Maybe that's Noah's way of saying that to size him up as host after his first night, or his first week, can't address how far he plans to go.

Nonetheless, he has no doubts the media will pronounce an instant verdict. With their insatiable appetite for content, they treat each passing moment as a potential milestone, however specious it may be.

So Noah, reconciled to the foibles of the media, and eager to lampoon them for it, appears calm as he prepares for opening night.

But don't think he won't feel terrified, he says, "the same way I feel now. I'm having nightmares! It's terrifying, it really is. But it's also extremely exciting. I'm trying to enjoy every moment of it."