The president is wasting no time in following through on his frequent campaign trail vows for retribution – with a torrent of purges and pardons.

Trump’s sending a chilling message through the US government: officials who cross him, investigate his alleged abuses of power, or join his critics once they leave office must beware his fury. Their livelihoods and even their lives could be at risk. But those who act in his name, even violently, like January 6, 2021, convicts, can expect protection.

The reckoning gathered pace on Monday.

- More than a dozen career officials, who worked on the Justice Department investigations into Trump and who should have civil service protections, were fired after being told they could not be trusted to “faithfully” implement his agenda.

- In another development, the administration opened a “special project” to take concrete steps to probe prosecutors who oversaw criminal obstruction cases against certain January 6 defendants that were ultimately tossed because of a Supreme Court decision last summer.

- These steps followed the dismissal of more than a dozen government agency watchdog officials known as inspectors general. It was lost on nobody that the official who informed Congress about Trump’s pressure on Ukraine to investigate Joe Biden, which led to Trump’s first impeachment, was an intelligence community IG.

- Last week, Trump stripped security details from some former key officials, including former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and former national security adviser John Bolton, who are facing threats from Iran after serving Trump during his first term.

- Trump’s legal maneuverings came alongside an escalating initiative to strip the government of top layers of the civil service. In another shocking move, the administration put about 60 senior career officials at USAID on immediate leave, following Trump’s executive order that froze almost all foreign assistance.

- As the president targeted government officials who did not break the law, Washington is still reeling from the pardons and commutations offered to thousands of January 6 rioters, some of whom who beat up police officers in 2021.

Trump is learning lessons from his first term, but is he acting legally or ethically?

These moves show Trump is determined to learn from his first term, when he was often frustrated by the checks and balances of government and believed he was thwarted by career officials.

A recurring question over the next four years will be whether the unprecedented actions from Trump are those of an anti-establishment disrupter that simply offend normal presidential decorum or whether they are illegal or corrupt.

Conservatives argue that Trump, after winning an election and saying exactly what he’d do with a second term, is well within his rights in gutting the government. Many Republicans before Trump felt that the federal bureaucracy actively thwarted right-wing policies that voters installed a president to pursue. And one reason Trump triumphed last November was his case that the federal government was failing the American people in multiple ways.

Many Republicans also agree with the president’s claims that the multiple criminal investigations against him over the last four years amounted to political persecution. Once that is accepted, the line between career and political appointees in the DOJ becomes blurred for many conservatives who believe the entire legal system is corrupted and biased.

Still, Trump’s recent efforts to apparently thwart accountability are extraordinary. In any normal administration – one not characterized by a flood-the-zone strategy of incessant presidential power plays – any one of them would be a scandal. For example, former first lady Hillary Clinton’s firings in the White House travel office in 1993 spawned an ethics brouhaha investigated by the DOJ and the FBI that only ended in the last year of the Clinton administration with no charges.

Presidents might win mandates, but that doesn’t give them the right to break the law. Trump’s administration failed to give Congress the required 30 days of notice of the dismissals of the inspectors general, raising concern even among GOP senators. And while presidents often dismiss politically appointed prosecutors when they take office, career DOJ officials are supposed to be sheltered by legal protections.

Ken Buck, a former Republican congressman, told CNN’s Erin Burnett on Monday that the case of the dismissed career Justice Department employees was “unique,” motivated by political goals and was “wrong.”

The officials concerned, who are not accused of criminal wrongdoing, were notified by acting Attorney General James McHenry. He wrote: “Given your significant role in prosecuting the President, I do not believe that the leadership of the Department can trust you to assist in implementing the President’s agenda faithfully.” The administration is not even hiding that this is retribution since it references the prosecution of Trump in former special counsel Jack Smith’s investigations into election interference and his hoarding of classified documents.

Jennifer Rodgers, a CNN legal analyst, highlighted distinctions between Justice Department professionals in offices that are charged with carrying out political goals and prosecutors who work on criminal cases.

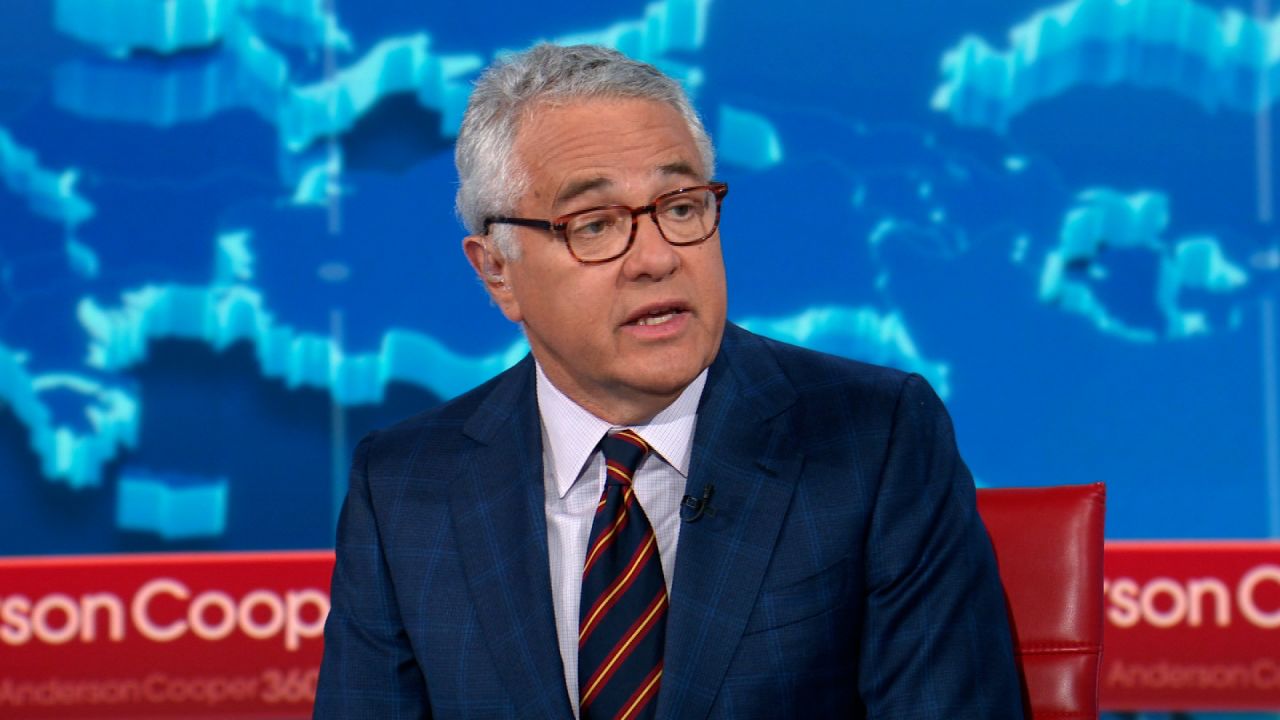

“The president shouldn’t have an agenda for criminal cases. … In the criminal realm, you are not supposed to have priorities, you are supposed to follow the facts, and apply the law, and charge who needs to be charged,” Rodgers, a former federal prosecutor, told Anderson Cooper.

‘Watchdogs or lapdogs?’

The history of Trump’s first term – when he, for instance, fired FBI Chief James Comey over the Russia investigation and turned on Attorney General Jeff Sessions for recusing himself – hints at motives for his recent actions. It seems clear he’s trying to intimidate career officials who might investigate him or block his expansive use of executive power. He’s also sending a signal to aides in his new administration they could end up like Pompeo or Bolton if they turn on him.

The ouster of the inspectors general, meanwhile, may ensure that the waste, fraud and political abuses that watchdogs are supposed to investigate may go unmonitored.

Mark Greenblatt, a former Department of Interior inspector general who was fired by Trump, said the greatest concern was the erosion of independent oversight.

“The whole construct of inspectors general, it’s based on us being independent, that we’re not beholden to a political party of any stripe, that we are there as the taxpayers’ representatives to call balls and strikes without any dog in the fight,” Greenblatt told CNN’s Kasie Hunt on Monday.

“What will President Trump do with these positions? Is he going to nominate watchdogs or is he going to nominate lapdogs? … If he goes down a path of nominating and appointing political lackeys, then I think the American taxpayers, Congress, stakeholders throughout the country should be up in arms.”

Constitutional remedies for those aggrieved by Trump’s actions are the courts and Congress. But neither may be up to the task.

It’s not clear that the administration so far really cares that much about legal sanctions, and the president always uses his time-worn tactic of prolonged appeals to belabor any legal dispute. There’s also no guarantee that a Supreme Court that last year granted Trump substantial immunity for official acts would rule against him in a unique case testing the scope of presidential powers.

Republicans who control both chambers of Congress have shown little appetite for checking Trump’s power, having declined to convict him in two impeachment trials. And senators who have balked at his controversial Cabinet picks have quickly faced threats of primary challenges.

Sen. Lindsey Graham encapsulated prevailing sentiment about Trump’s power when commenting on the case of the dismissed IGs on CNN’s “State of the Union” on Sunday. The South Carolina Republican said Trump should have given Congress 30 days notice before ousting the officials, to comply with the law.

But he added: “The question is, is it OK for him to put people in place that he thinks can carry out his agenda? Yes. He won the election. What do you expect him to do, just leave everybody in place in Washington before he got elected?” Graham went on: “This makes perfect sense to me. Get new people. He feels like the government hasn’t worked very well for the American people.”

Senate Judiciary Chairman Chuck Grassley has long been a supporter of IGs. And he issued a statement on Saturday asking for more details. But it would be a surprise if the veteran Iowa Republican comes down hard on the Trump administration.

Another Trump ally, Sen Tom. Cotton, said Sunday that inspectors general serve at the pleasure of the president and “he wants new people in there.” But the Arkansas Republican did express disquiet at the president’s treatment of Pompeo and Bolton and others targeted by Iran and asked him to reconsider. “It’s better to be safe than sorry, because it’s not just about these men who helped President Trump carry out his policy in his first term,” Cotton said on “Fox News Sunday.”

“It’s about their family and friends, innocent bystanders every time they’re in public. It’s also about the president being able to get good people and get good advice.”

Trump was asked last week whether he would feel responsible if something happened to Bolton or Dr. Anthony Fauci, the former top infectious diseases official who faces politically motivated security threats because of his role in responding to the Covid-19 pandemic.

“No,” he replied.

A president who escaped two assassination attempts and will be surrounded by Secret Service officers for the rest of his life added: “I think, you know, when you work for government, at some point your security detail comes off.”