Jamie Dimon, head of America’s largest bank, JPMorgan Chase — and commonly referred to as the ‘president of Wall Street’ — spent much of this past year warning that there’s an elevated risk that the US experiences 1970s-esque stagflation, which is when economic growth stagnates while inflation heats up.

“I look at the amount of fiscal and monetary stimulus that has taken place over the last five years — it has been so extraordinary; how can you tell me it won’t lead to stagflation?” Dimon said at a conference in May.

His prediction, however, has been pooh-poohed by many leading economic voices; chief among them was Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, who said at a press conference in May, “I don’t see the stag or the ‘flation.”

That, of course, was before President-elect Donald Trump won the election. Now, Americans may have to actually brace for stagflation — something the nation’s economy hasn’t experienced in over half a century. This time around, though, fueled by tariffs.

Just over a month from now, Trump will have the power to levy tariffs on other nations at the flick of a pen. And once inaugurated on January 20, he has pledged to immediately impose a 25 percent tariff on Mexican and Canadian imports and increase tariffs on Chinese goods by an additional 10 percent.

On the campaign trail, he also promised to levy a 10 percent to 20 percent tax on all imports and increase tariffs on Chinese goods by at least 60 percent.

There are some doubts as to whether Trump will follow through with these plans and, instead, use them as a means to negotiate with other nations. However, if these significant, broad-based tariffs go into effect, it could send the US economy back to one of the most painful periods that took over a decade to resolve.

The US economy is miles away from stagflation right now

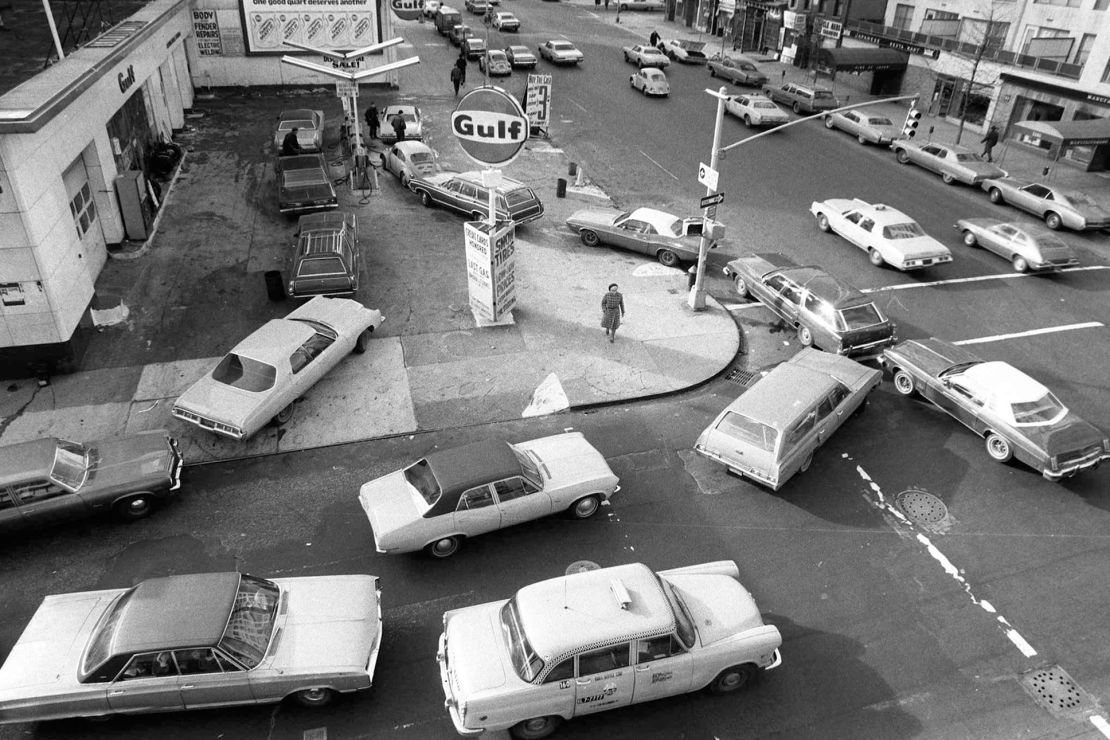

“I was around for stagflation. It was 10 percent unemployment. It was high single-digits inflation and very slow growth,” Powell said back in May, referring to when oil prices spiked during the Arab oil embargo in the 1970s.

When the Fed responded to high levels of unemployment in the 1970s by cutting rates to relieve pressure businesses faced, it later had to contend with higher inflation. To tackle higher inflation, central bankers raised interest rates. But that ushered in more unemployment.

To break that vicious cycle, the Fed opted to prioritize getting inflation down by aggressively raising interest rates, even if it meant the economy would enter a recession, which it did.

The US economy currently isn’t anywhere near the conditions the Fed faced during much of the 1970s and 1980s. Though it’s risen over the course of this year, at 4.2 percent, the nation’s unemployment rate is two percentage points lower than the average seen over the last 50 years.

Meanwhile, inflation has cooled significantly over the past two years. It’s now just a touch above the Fed’s 2 percent target. Getting it down to that exact level has proved to be challenging.

Overall, the economy grew at an annualized rate of 2.8 percent last quarter, a slightly weaker pace than the prior quarter, but nevertheless impressive considering the Fed raised interest rates to the highest level in over two decades to fight inflation, which peaked at a 40-year high two years ago. (The Fed started lowering rates earlier this year and is expected to continue to cut at its meeting this week. However, it can take years for the effect to be felt across the economy.)

The path to stagflation

The tariffs Trump has floated aren’t inherently inflationary, Michael Feroli, chief US economist at JPMorgan, told CNN.

While they certainly have the power to make many, if not the majority, of goods Americans buy more expensive, that could just be essentially a one-time bump in the prices of goods, similar to a sales tax increase, he said. But higher tariffs can quickly fuel cascades of price increases if Americans expect higher inflation because of them and demand higher wages, which, in turn, could result in businesses continuing to raise prices.

And if new tariffs are imposed in a “haphazard” and “hasty” way such that businesses don’t have ample time to reconfigure their supply chains, it could significantly hamper economic growth by also forcing businesses to pull back on any new investments due to heightened uncertainty, Feroli said.

Stagflation could also materialize if other nations were to respond with retaliatory tariffs on US-produced goods, likely leading employers to lay off workers as a result, he said.

Though Feroli believes the risk that the US economy experiences stagflation is higher now compared to earlier in the year, it’s not the base case he and the team of economists he works with are predicting at the moment. That’s because they aren’t forecasting inflation jumping by more than a few tenths of a percentage point from current levels, partly because he believes the Trump administration will give US businesses sufficient time to respond to higher tariffs if they’re set in motion.

Wells Fargo economists share a similar view to Feroli.

“These tariff increases, if implemented shortly after Inauguration Day, would impart a modest stagflationary shock to the U.S. economy, boosting our inflation forecasts in the near term, but also dampening our economic growth outlook,” they said in a note last month, published shortly after Election Day. “Should this occur, the probability of a stagflation scenario in our growth model would likely increase.”

“That said, there is tremendous uncertainty about future potential policies,” they cautioned.