Even within the context of the past 13 months, the events of Wednesday’s soccer match confound. Port Said’s home team enjoys a rare victory, and fans celebrate by raiding the pitch and murdering scores of Ahly supporters.

Reports of decapitations, bodies being thrown from the stadium’s uppermost bleachers, and defiled corpses come pouring in across news and sports shows, while live images reveal rows of central security officers watching from the sidelines, doing little, as had come to be expected of them.

The scene left a gash in the national consciousness, and questions piled up immediately. As retired goalkeeper Nader al-Sayed lamented during his televised sports show’s live coverage of what has been since repeatedly referred to as a massacre, “This is not normal. This is the result of a malicious and sinister plan, carefully plotted and expertly perpetrated, and we all know by whom.”

“This past year has seen obvious attempts at destabilizing the nation, and we have remained silent through them all,” Sayed continued, speaking on behalf of Egypt’s considerable hardcore soccer enthusiasts. “We were silent as our institutions were burned to the ground, we were silent as our women were publicly dragged and beaten. We cannot remain silent any longer.”

What Sayed failed to either realize or acknowledge was that one section of the Egyptian soccer fanbase — arguably the most devoted — has not been silent. In fact, the ultras have played an undeniably significant role in the ongoing revolution, as attested to by revolutionaries.

“The ultras are not politically active,” says Mohamed Gamal Beshir, author of the recently released “Ultras Book” and founder of the Zamalek White Knights, who claims that although certain football fangroups which inspired the Egyptian ultras, such as ones in Italy or England, might have political connections or adhere to fascist ideologies, their Egyptian counterparts are just casual, albeit passionate, fans uninterested in “mobilizing as a group or anything like that.”

Rather, it is their unchecked (i.e., youthful) passion, not to mention their years of experience in dealing with a police force that widely targeted them as thugs and hooligans, that has earned the ultras their revolution-era reputation as either an unruly mob or heroic “lions” safeguarding the national pride.

“They are heroes, there is no question about it,” insists Samah al-Nakkash, a 44-year-old mother, and unlikely member of the protest that swelled outside of Cairo’s Ahly soccer club the morning after the massacre in Port Said. Her soccer-loving son, she says, is not an ultra but his friends are, “and they are lions. They are always organizing popular committees on the street, and protecting girls, and attacking the police officers that try to dishonor them.”

As the protesters shuffled in an attempt to get their planned march to Parliament started, Nakkash continued to praise the young men who had nurtured their love of sport into fully-blossomed patriotism.

Nakkash — and likely all others desperate for a shred of optimism to cling to in increasingly troubling times — would be dispirited to hear that the ultras have not been organizing popular committees or girl-protecting squads.

“Yes, we have been on the street, and yes, we have been participating in the revolution,” says Hisham Abdel Rahman, a member of the Ultras Ahlawy unfortunate enough to have been in the bleachers at the Port Said game. Of the role he and his ultra-brethren have played in the uprising, Abdel Rahman explains, “We do these things as Egyptians, not as ultras.” However, that may soon change.

The horrors the 19-year-old witnessed during the Port Said-Ahly clash have been widely documented by its survivors. His firsthand account has left him convinced that the incident was planned (“The gates were welded shut, during the game there were weapons being openly exchanged in front of the police, and there were new rows of iron seats that I had never seen in that stadium before”), but it is the aftermath that has left him truly shaken.

Immediately following the mayhem — and, to a lesser extent, as it was unfolding — there were those who publicly described it as being the result of typical football hooliganism. On the surface, these condemnations were not unreasonable — Port Said and Ahly have a history of rivalry — but fail to hold up to the slightest scrutiny.

“Yes, there’s rivalry between the two teams, as there is between most teams playing any sport anywhere in the world,” says Abdel Rahman. “But this rivalry has never killed anyone. The way those people [supposed Port Said fans] attacked us had nothing to do with sports, or team loyalty. Especially because they won, and it was an unprecedented victory for them, and the real fans that were in the stands did actually leave the stadium to go celebrate.”

“We’ve had more serious rivalries with teams from other countries,” Abdel Rahman’s fellow ultra (who was not at the Port Said game) and member of the Ahly club march, Ahmed, chimes in. “But even those rivalries never led to anything as brutal as what happened in Port Said.”

Yet, similar claims made by others present at the scene and corroborated by officials have not stopped certain detractors. The funeral held by the Ahly sporting club had not even ended when the Muslim Brotherhood issued a statement denouncing the entire ultra movement as “hooligans” responsible for dragging the nation to the brink of the abyss. For the ultras, these accusations only add insult to a fresh and critical injury, while simultaneously channeling a current of public anger in a potentially explosive direction.

“We hear this all the time — ‘the ultras are vandals,’ ‘the ultras are criminals and thugs,’” Ahmed says. “People will think what they want to think, but this incident has shown that there are more people who know what we truly are than those who think we’re outlaws or sociopaths.”

For others, though, it comes down to a much simpler solution: “If people want to call us thugs,” Abdel Rahman says grimly, “we’ll give them thugs.”

Conversely, and as noted by Ahmed and evidenced by the staggering turnout at the Ahly club and various other beacons of support throughout the capital, the tragedy at Port Said has led to an outpouring of support for the institution and its fans; so much so that in writing an article about ultras, it became difficult to distinguish between genuine members, and those only claiming to be.

Mohamed Awad and Hatem Madkour — 27, 35, and both attending the Ahly march in black mourning attire — described at length “what it means” to be an ultra, before admitting that they were only soccer fans who “really love Ahly and its ultras.” Awad and Madkour were not the only self-appointed ultras in the crowd, which also included ultras from rival clubs, as well as people with no interest in soccer to speak of.

“This isn’t about soccer, or sports, or Port Said or Cairo,” declares Sherif Tammam, moving with the crowd toward Qasr al-Nil Bridge and, beyond it, Tahrir Square, already overflowing with like-minded protesters. “This is about something much bigger than that.”

Despite his loyalties to Zamalek — traditionally Ahly’s arch-nemesis — Ramy Tabrizi walks through the crowd carrying flags belonging to both clubs. “We’re all Egyptian,” is his reason. “We’re all being lied to, again.”

“What happened in Port Said was the Interior Ministry’s revenge for the revolution that brought them to their knees,” Tabrizi states. “It’s revenge for us refusing to let them keep us down, and refusing to give up on the revolution. This is their new role now, to carry out their revenge.”

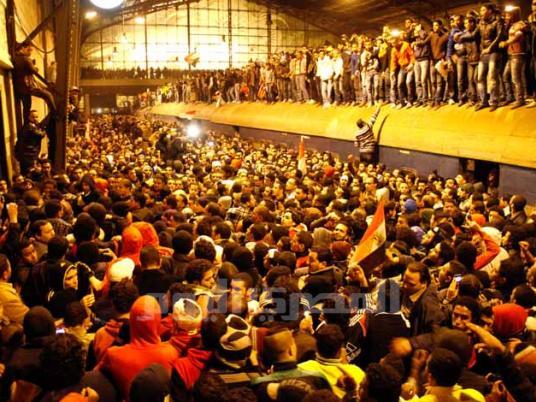

It seems the revolution has given new roles to everyone — be it “politician,” “victim,” “thug,” “protester” or any of several others. The definitive characteristics of each are not set in stone, instead depending on personal perspectives, and pockets of popular opinion. As the Ahly club protesters marched onwards to what would be another 36 hours of violence, chants of “ultras are not thugs” broke out, along with a sub-chorus of promises and threats to the nation’s police and ruling military forces. “It’s all going to burn tonight,” one teenager was heard gleefully predicting to a friend.

Essentially a leaderless movement in a leaderless revolution, the ultras seem to have less control than most over how they’re perceived by a public drunk on patriotism, paranoia, and the endless confusion that lies in between.