US-Egypt relations have soured following the latter’s recent blows to its most important benefactor. For the first time, US aid to Egypt appears at stake. At the outset of revolutionary upheaval last year, voices in the US media echoed optimism and confidence in the Egyptian military’s ability to rule the country and oversee the transition period, while others urged caution in light of the fact that Mubarak's regime had emerged from, and had been backed by, the same military.

On 31 January 2011, Matthew Axelrod, former North Africa and Egypt director in the US secretary of defense’s office, comforted US readers who had been following protests for nearly a week.

“There is some reason to believe the military could prove a positive force for change,” he wrote in Foreign Policy.

“These officers envisioned themselves as guardians of the Egyptian people — not the regime.”

But Axelrod did not fail to note the tension that exists between the generals' economic and political interests on the one hand and the need to maintain their credibility by siding with the people on the other.

“A middle solution is conceivable, where the military would not stand in the way of a transition government should it receive assurances that its affairs will remain untouched from reform,” he wrote.

Writing on his blog the same day, Steven Cook, senior fellow for Middle Eastern studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, made the opposite argument: “Recent events highlight that the armed forces is the pillar of the [Mubarak] regime” and that it “is not giving up its informal link to the presidency and the regime.”

Although the US forsook its longtime ally, it maintained relations with Egypt’s military, a decision made apparent by the White House initial support for Omar Suleiman's presidency. The US and Egypt’s military ties are decades-old. The US has given the Egyptian military between US$1 and $3 billion a year since 1979. A leaked State Department document from 2009 states that “the tangible benefits to our mil-mil relationship are clear: Egypt remains at peace with Israel, and the US military enjoys priority access to the Suez Canal and Egyptian airspace.”

Following the Egyptian uprising last year, and as the SCAF subjected thousands of civilians to military trials, silenced criticism, and used excessive violence against protesters, killing dozens, American columnists worried that unconditional support for Egypt's military would adversely affect US credibility among citizens who would determine their country’s fate through the ballot box. They advised the Obama Administration to become more vocal in its criticism of the SCAF.

November’s violent crackdown on demonstrators, which left at least 45 dead, induced White House Press Secretary Jay Carney to issue a neutral statement calling for “restraint on all sides.”

A Christian Science Monitor article on 22 November by Egypt correspondent Kristen Chick remarked: “As abuses have stacked up, the US has mostly refrained from public criticism of Egypt's military, whose $1.3 billion in US aid could come under review if critics in Congress prevail.” The article attributed Washington's silence to “fear of losing access to and influence on the military council at a delicate time of transition.”

On 25 November, the White House finally issued a statement calling on the ruling military to “empower the new Egyptian government with real authority immediately.” It was the first time the White House publicly criticized the Egyptian military, but no mention was made of the possibility of conditioning military aid.

Five days later, the New York Times published an op-ed by Steven Cook and Marc Lynch denouncing the US response: “The administration has articulated a new standard of legitimacy [in the region]; that leaders who use violence against their own people forfeit their standing to rule. The same standard should apply to Egypt.”

The authors advised Washington to exert public pressure on the ruling military for “the months of political mismanagement and the bloodshed committed under its auspices,” and suggested conditioning aid on the transfer of power to civilians.

Subsequent military-led violence against protesters, particularly in December, pushed Clinton to issue a statement against the violence without naming the military. “I am deeply concerned about the continuing reports of violence in Egypt. I urge Egyptian security forces to respect and protect the universal rights of all Egyptians, including the rights to peaceful free expression and assembly. Those who are protesting should do so peacefully and refrain from acts of violence,” she said.

Reports of the violence began to reveal less sympathy with the victims. The Wall Street Journal included passers-by accounts describing demonstrators as having “limited political awareness” and as “kids who throw rocks with smiles on their faces.” Writing in Foreign Policy, Cook went as far as to describe protesters as possessing “no moral force, no common cause, and no sense of decency.”

Although the mainstream media in the US did not press the Obama Administration to take drastic measures following the military crackdown, it did not spare the SCAF from criticism. A New York Times editorial stated that “blaming protesters is unconvincing in the face of shocking images of the military's conduct.”

In December, the US Congress moved to implement restrictions and requirements on aid in a new spending bill in an attempt to cut the deficit. But so far, the White House has pushed back on the proposal out of concern over “the foreign policy prerogatives of the President.” The bill makes aid to Egypt conditional on the secretary of state's certification that the Egyptian government supports the transition to civilian government, protects freedoms, and upholds the 1979 peace treaty with Israel.

But Clinton assured Egyptian Foreign minister Mohamed Kamel Amr that the administration opposes the Senate conditions.

“We will be working very hard to convince the Congress that that is not the best approach to take,” Clinton said before Congress backed the new restrictions. “We don’t want to do anything that in any way draws into question our relationship or our support.”

In both official corridors and mainstream media, substantial threats to withhold US military aid increased after several NGO offices were raided by the Egyptian military and police in late December, including three American institutions that receive US government funding. State Department spokeswoman Victoria Nuland announced that it was “deeply concerned” by the raids, calling them “inconsistent with the bilateral cooperation we've had over many years.”

David Kramer, president of Freedom House, whose Cairo office was raided, wrote in a column in the Washington Post: “The Obama Administration should tell Egypt's military council unambiguously that assistance will end unless such behavior ceases.”

In its news pages, the Washington Post headlined the incident: “Egyptian military gambles by raiding pro-democracy groups.” The article quotes Michele Dunne, former staffer of the National Security Council, saying, “if the Egyptian military is not allowing a real democratic transition to civilian rule, if it is harassing civil society, and if it is trying to prevent the United States from funding civil society groups, the time has come to suspend the military aid until things improve.”

For the first time, the White House hinted that the funds could be withheld in light of the military crackdown on NGOs. “We do have a number of new reporting and transparency requirements on funding to Egypt that we have to make to Congress,” Nuland said after the raids.

However, the US appeared to accept reassurances given by Field Marshal Hussein Tantawi to US Defense Secretary Leon Panetta. The latter conveyed his “appreciation for Tantawi's prompt decision to halt the raids,” “reaffirmed the importance of the US-Egyptian security relationship,” and “made clear that the United States remains committed to the strategic partnership.”

Assistant Secretary of State Jeffrey Feltman reiterated the same reassurances in a January interview with Al-Masry Al-Youm, saying, “The administration has continued to make a very strong case for our assistance to Egypt.”

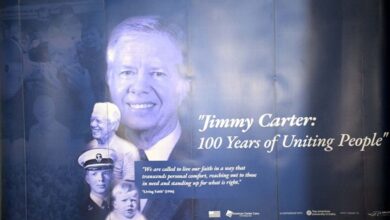

At the same time the US retreated from pressing the SCAF to ensure a full transfer of power, former President Jimmy Carter met with Field Marshal Hussein Tantawi and returned home with the view that SCAF was unlikely to cede power completely. He insinuated that a consensus between Islamist groups and the military may be the best guarantee for stability and the preservation of US interests.

“I think it is probably going to be inevitable, and I don't think it is going to be detrimental for the military to retain some special status,” he said. “If the civilian leadership decided to give the SCAF immunity from prosecution, say for the death of the people in Tahrir Square over the last few months, I would have no objection to that. Protecting the military budget from full civilian scrutiny might be another point where civilian political leaders could compromise,” he told the New York Times.

But Washington’s anger following the NGO raids soon intensified. On 26 January, Egypt barred six American nationals from leaving the country, including Sam LaHood, son of US Secretary of Transportation Ray LaHood, who directs the Egyptian program of the International Republican Institute, one of the raided NGOs.

The move instigated diplomatic fury. Nuland called on Egypt to allow the Americans to depart without delay. Advocates of conditioning military aid in Congress, including Democrats, became more vocal. Senate Appropriations Committee Chairman and close Clinton ally Daniel Inouye expressed support for fresh conditions on US military aid to Egypt, despite having been an opponent of conditionality in the past. He and other democrats pressed for the conditions despite objections from the administration.

“We no longer have a blank check for the Egyptian military,” Democrat senator Patrick Leahy told Politico.

The US media was quick to expressed outrage at the Cairo-incited standoff. A New York Times editorial stated: “It is beyond us why the generals would keep pressing this destructive dispute. They must let Mr. LaHood and the others go immediately.”

The Washington Post’s editorial's headline on 1 February read: “Egypt's witch hunt threatens a rupture with the US.”

“The generals regard this funding as an entitlement, linked to the country’s peace treaty with Israel. They appear to believe that Washington will not dare to cut them off, even if Americans seeking to promote democracy in Egypt are made the object of xenophobic slanders and threatened with imprisonment,” wrote the editorial board.

It called on the Obama administration to “be prepared to take an uncompromising stand” instead of merely warning Tantawi that the aid was at risk and blaming congress for attaching conditions over the administration's objections.

In a piece published by online magazine Slate titled “For Egypt, Aid Not Ransom,” Michael Moran argued that “reforming Egypt’s army, indeed, taking it down a peg or two, is a prerequisite for making progress toward an Egyptian democracy. The US should put that money where it will do some good, or at least, where it will prevent something bad.”

It remains to be seen whether the Obama Administration will affect any changes to its annual military aid to Egypt in light of the current strain in US-Egypt relations. The administration is finalizing its budget for the 2013 fiscal year, which will be presented on 13 February and is expected to include continued assistance for Egypt's military.

On Sunday, Egyptian state media announced that 19 American nationals were referred to criminal trials in the NGO funding case, including LaHood. In light of this development, the media in the US will likely step up its tone against the SCAF.