On 17 December 2010, 26-year old Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia after the local authorities confiscated his vegetable stall. “How many people would have predicted that the death of a vegetable seller in Tunisia would set off this extraordinary chain of events that have happened since the end of 2010?” asked Canadian historian Margaret MacMillan on Monday evening at the American University in Cairo.

Very few can claim to have foreseen the uprisings spreading so quickly across the Middle East. This, however, does not discredit history as a discipline, she argued. Bouazizi’s decision to set himself on fire was an individual choice – a human factor, which social scientists often try to control in their studies. “In decisive moments, the human factor can, however, send events in one way or another,” MacMillan said.

Author of “Dangerous Games: Uses and Abuses of History” (2008), as well as the multiple-award winning “Paris 1919” (2002), which surveys the post-WWI peace process, MacMillan spoke in defense of history while unpacking its possible abuses in policy-making, particularly at times of crises and transition. The world is experiencing significant change with the rise of new economic and military powers like China and India vis-à-vis the US and countries across the Middle East are undergoing political change. To this end, much can be drawn from past experiences, explained MacMillan – particularly to avoid similar mistakes.

“History cannot be used to predict the future,” MacMillan told her audience. It can, however, give warning signs and offer useful analogies for interpreting events – given that you get the right one. “It can be very dangerous if you get a wrong analogy and cling to too long,” she added. One that policymakers have been extensively using and at times applying to inappropriate situations, she added, is the appeasement analogy.

In the 1930s, increasing concessions were made to Hitler and Mussolini for fear of having a second world war. This appeasement policy proved its failure with the outbreak of WWII and ever since has been associated with weakness. Bush’s decision to topple the Saddam regime, for instance, was wrongfully supported by the appeasement analogy. Saddam was not going to start a third world war like Bush suggested, yet the decision was promoted on those grounds, she explained. Similarly, the British and the French attacked Egypt in 1956 out of baseless fear that former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser would try to control the Middle East after he nationalized the Suez Canal.

The abuses of history do not only stem from incorrect analogies, but often from the loss of veracity in historical writing. “History taught us” is a recurring phrase among people of all backgrounds, explained MacMillan. Yet many historical accounts offer narrow perspectives on events. Robert Kaplan’s “Balkan Ghosts,” for instance, blamed the Balkan conflicts on ancient hatreds with no mention of external forces. It is argued that Kaplan’s analysis were fundamental to Former US President Bill Clinton’s decision not to interfere with the Yugoslavian situation. The book, as MacMillan describes it, ignored that those communities lived side by side for centuries with periods of peace.

Attempts to control the subversive power of history date back to prehistoric times with various ruling regimes altering or destroying documents that conflicted with desired legacies. In 221 BC, the great Chinese emperor Chi’n asked all scholars in the land to bring him their books. He then killed them all ensuring that only his vision would persist, recounted MacMillan.

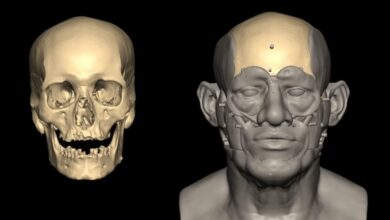

Egyptians remember when the state-run Al-Ahram newspaper published last September a doctored image of former President Hosni Mubarak walking in front of key figures at the Middle East peace talks in Washington. MacMillan, however, cited a similar example that dates back much further. A picture of the communist leaders of the 1917 Russian revolution showed Stalin standing at the far end from Lenin. As Stalin rose to power, he got rid of his contemporaries and began cutting them out of the picture. “In the end, it looked like Stalin was standing over Lenin’s shoulder telling him what to do,” MacMillan said. Since the image alteration techniques were then primitive, there was a time when the image of the Russian leaders showed one of them standing on three legs.

History has been used to create divisions through emphasis on ethnic and religious identities, emphasizing a “self” and an “other.” It’s also been used to convince people that the status quo is what was meant all along. It can nevertheless help make educated guesses about the future.