One of Egypt’s pioneering filmmakers, Kamal El Sheikh, was born on 5 February 94 years ago.

Sheikh is known as the “Egyptian Hitchcock,” after British film director Alfred Hitchcock, because of the similarities between the two filmmakers’ styles.

Sheikh, who died in 2004, directed 35 films. His first movie was “House No. 13” (Al-Manzel Raqam 13) in 1952 and his last was “The Time Conqueror” (Kaher al-Zaman) in 1987.

Unlike Hitchcock, whose first few films were not that successful, Sheikh’s “House No. 13” garnered both commercial success and critical acclaim.

The film’s plot was quite complex compared to mainstream cinema at that time, which tended to rely on simplistic romantic themes and songs. In the experimental thriller, a psychiatrist hypnotizes one of his patients to kill people.

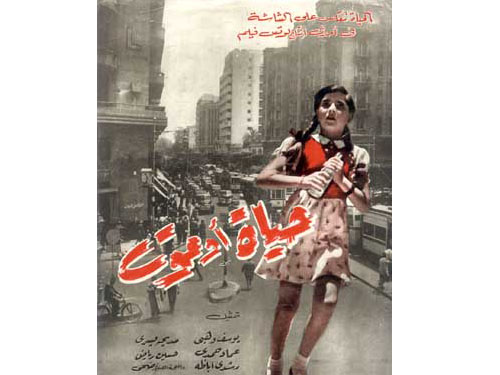

But Sheikh’s directorial and intellectual style crystallized more in his third film, “Life or Death,” (Hayat Aw Mout), produced in 1955. Critics consider “Life or Death” one of the greatest Egyptian films ever made. It is one of the few films made during that era with Cairo as its main focus.

Ahmed Ibrahim, a state employee, finds himself broke a day before Eid. But, as a loving father, he spends all his money on a new dress for his 8-year-old daughter. Tensions arise with his wife over their financial difficulties and a medical condition he suffers intensifies, while his medication runs out.

His daughter decides to go buy him medicine from the 24-hour pharmacy in Attaba because pharmacies in their neighborhood in Old Cairo are closed for the Eid holiday. The pharmacist gives her the wrong medicine, which could cost Ibrahim his life.

The pharmacist then tries to find the young girl, and contacts the most senior police officer in Cairo to help him.

What is most interesting about the film is Sheikh’s vision to make a film that captures the dynamics of Cairo’s main streets. In “Life or Death,” viewers tour Cairo through two parallel lines: One follows the daughter searching for a pharmacy, taking the metro from Old Cairo, through Qasr al-Aini, Tahrir Square and Bab al-Louq. The second follows the police searching for the daughter through many of the city center’s most well-known streets.

We see the wide, clean streets commuted by Cairo’s 2.5 million inhabitants at the time. Trees and greenery surround the Nile banks, and the city’s architecture was still harmonious.

Sheikh’s talent shined further when he focused on how the press could invent a criminal out of a normal person in his 1962 film adaptation of Naguib Mahfouz’s “The Thief and the Dogs” (Al-Lis wal Kilab).

In his 1975 movie “At Whom Do We Fire?” (Ala Man Nutliq al-Rossas), Sheikh was one of the first artists to investigate the transformations Egypt underwent under former Egyptian President Anwar Sadat.

Mostafa shoots dead the CEO of a state-owned company that builds low-cost housing units. As investigations of the killing unfold, we discover how corrupt and desperate Egypt had become because of a bureaucracy that deserved to be killed, according to Sheikh.

In most of his movies, Sheikh was an ardent advocate of equality, justice and retribution.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.