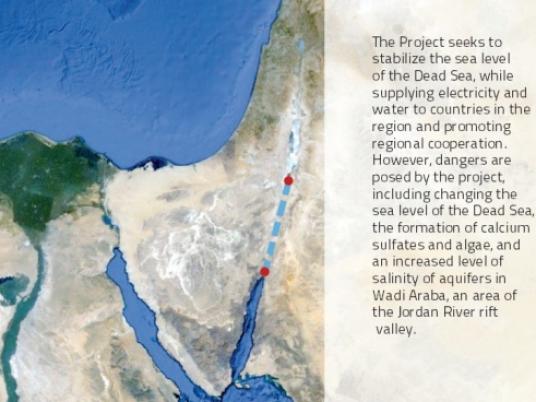

In an attempt to curb the rapidly declining water level of the Dead Sea and allow for its gradual replenishment, the World Bank has been studying the possibility of transferring water from the Red Sea to the Dead Sea almost a decade.

The organization recently published a project feasibility study on the idea, assessing its environmental and social impacts prior to a round of public consultations scheduled to take place in mid-February.

Reports show that a large-scale transport of seawater from the Red Sea to the Dead Sea is technically possible, either by using a tunnel or buried pipelines. But many environmental experts and organizations have raised concerns about the project, which they say poses environmental, economic and social risks.

The governments of Israel, Jordan and the Palestinian Authority have together undertaken the project, which aims to save the Dead Sea from further environmental degradation. The sea’s water level has dropped by 25 meters in less than 50 years and continues to drop at a rate of about one meter per year.

Desalinating water and generating electricity at affordable prices for Jordan, Israel and the Palestinian Authority are also considered important goals for the project. However, this is contested by some.

“Israel is actually the main benefactor from such a project, as it’s the only country that has the technological capacity and financial resources to benefit from the desalinated water,” says Lama El Hatow, PhD candidate at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands and co-founder of the Water Institute of the Nile. “This technology is too expensive for Jordan, and the water would probably never reach Palestine, as it would have to pass through Israeli territories first.”

In a jointly signed letter to the World Bank from May 2005, the beneficiary parties requested that the bank coordinate donor financing and manage the implementation of the study, considering it an important independent and trusted facilitator.

Friends of the Earth Middle East, a leading environmental organization nominated by The Global Journal as one of the world’s top NGOs in 2013, sees flaws in the study itself, saying consultants should not have been chosen by the Israeli, Palestinian and Jordanian governments. The World Bank should have instead hired international consultants in an independent and comprehensive fashion, the group says.

Mahmoud Hassan Hanafy is one of the Egyptian experts who studied the project’s feasibility and its potential impacts on Egypt. He is the scientific adviser for the Hurghada Environmental Protection and Conservation Association and a marine environment professor at Suez Canal University.

He explains that there are two ways to establish the conduit. The first involves creating a seven-kilometer canal from the tip of the Gulf of Aqaba, then pumping water from the canal into tubes up to 20 meters over sea level, and then down a valley into an open channel to the Dead Sea.

“This case would have very limited influence on the water circulation and distribution in the area,” he says.

The second scenario would involve pumping water at a rate of 2 billion cubic meters annually — 60 cubic meters per second — from Eilat in Israel. This would lead to a modification of the water circulation pattern, he says, and activate a phenomenon called “vertical water mixing” that would eventually increase the growth of algae and choke the coral reefs in the process.

Hatow sees other serious environmental risks.

“In addition to the algae formations, the saltwater intrusion into the aquifers in the region along the canal route would cause the salinization of these aquifers,” she explains.

She says Dead Sea marine life would also be affected, adding that it is “never advisable” to put alien species and organisms into a new environment. Transferring these organisms to a whole new ecosystem could alter their behavioral patterns and cause irreparable damage to the recipient ecosystem.

Hatow also worries about the potential decline in sea level in the Gulf of Aqaba, which could harm coral reefs in the Gulf.

“From cities like Taba, Dahab, Nuweiba and down to Sharm el-Sheikh, the Gulf of Aqaba hosts the coral reefs that Egypt’s tourism benefits from,” she asserts. “This essentially may alter the reef system and reef bed in this region, and hence the ecosystem, and, of course, tourism in return.”

Ultimately, Hatow suggests another alternative that could address the Dead Sea’s shrinking water levels — without the environmental side effects.

“Other alternatives would include conservation of the Dead Sea as a protected area and not exploiting its waters for salt deposits and minerals that are collected and sold to premium markets,” she says.

Friends of the Earth Middle East has conducted an independent socioeconomic and environmental assessment of the proposed Red Sea-Dead Sea canal project.

On their website, the group argues that establishing such a project raises many questions it says weren’t adequately addressed by the World Bank study.

The organization says the study did not address considerations regarding the changes to the Arava Valley during and after canal construction, or potential changes to the Dead Sea’s chemical composition that could result in the loss of its unique characteristics.

The organization also says the World Bank report did not answer questions about what would happen when the Dead Sea is filled up and can no longer receive desalination brine generated by desalination activities. It says it regrets that the World Bank did not address the threat of gypsum and other microorganisms caused by mixing the two seas’ waters.

Hanafy is adamant that the project’s economic drawbacks are even more significant and dangerous than the environmental concerns.

“Having a canal extended to the Dead Sea will encourage businessmen to establish a lot of tourist projects that will, in turn, create competitors to our projects in the Aqaba area,” says Hanafy. “This will reduce the economic value of the biodiversity in Egypt, which is an important tourist product that contributes to the national income. It will also affect the job opportunities there and thus influence social life in the region.”

He also thinks the project could impose national security risks, because the canal would be located in the Negev region, in which some Israeli nuclear reactors and industries are located. Because cooling nuclear reactors that use water perform better than with air, he says, he thinks it should be clarified whether Israel would be allowed to use desalinated Red Sea water for such uses.

“The project must be studied in more depth by a number of experts in different fields within a three-party agreement in which Egypt must be considered an important part,” he notes.

The World Bank said in a statement that the project must be decided upon by beneficiary countries, and that it is up to them to decide whether to move forward, based on the study findings.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.