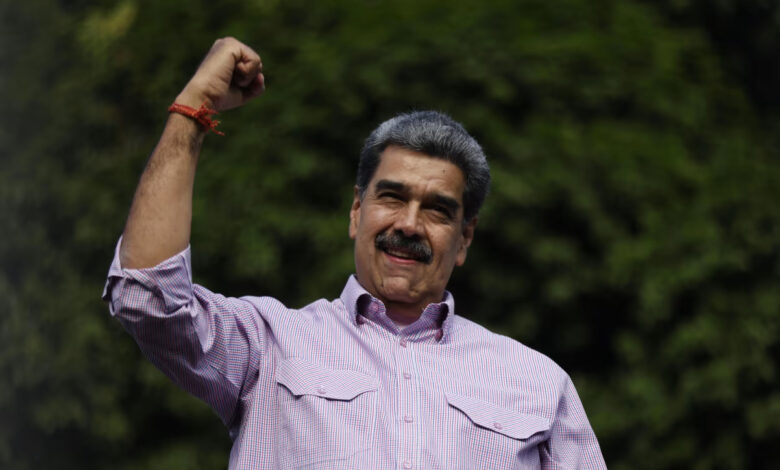

What will become of Nicolas Maduro? With a $50 million bounty on his head, the CIA openly active in Caracas and US forces mustering in the Caribbean, pundits and politicians throughout the Americas are opining on the Venezuelan president’s fate.

Some are counting on the United States deposing him, Saddam Hussein-style (or Salvador Allende-style, or Manuel Noriega-style). In the past two weeks, prominent neoconservatives Bret Stephens and Elliott Abrams have argued in favor of overthrowing Maduro outright in columns in the New York Times and Foreign Affairs.

Others wonder if Maduro might leave of his own volition. On Wednesday, the foreign minister of Colombia, Rosa Yolanda Villavicencio Mapy, suggested that Maduro’s negotiated exit from the presidency would be the “healthiest” option available.

“I believe he has indeed considered it, that there could be a way out, a transition, where he can leave without having to go to jail, and where someone can come in who can make that transition and where there can be legitimate elections,” Villavicencio Mapy told Bloomberg News. “It would be the healthiest thing to do.”

Soon after, Colombia’s leftist government clarified that the minister’s comment should not be construed as an endorsement of Maduro relinquishing power, emphasizing that Colombia has no interest in interfering “in the internal affairs of other countries.”

Defiance despite a bad year

It’s been a difficult year for Maduro, who became president of Venezuela in 2013 after the death of its charismatic leftist president Hugo Chavez.

His self-proclaimed victory in the 2024 Venezuelan election was disputed by the country’s opposition and went unrecognized by most of the Western world. The US has long considered him a criminal, accusing him of heading a criminal structure known as “el Cartel de los Soles” (the Cartel of the Suns), which most experts say does not technically exist.

Recently, the Trump administration labeled el Cartel de los Soles a terrorist group, creating a potential opening for US military strikes in Venezuela.

To make matters worse for the embattled president, his political enemy, opposition leader Maria Corina Machado, won the Nobel Peace Prize in October. From hiding, Machado has warned that Maduro’s time as president is coming to an end, promising a “new era” for Venezuela.

CNN spoke to experts about what might lie in store for the Chavista leader, all of whom agreed that Maduro and his government are extremely unlikely to forfeit power willingly.

Elias Ferrer, a Caracas-based risk consultant at Orinoco Research, said that Maduro and his colleagues are keenly aware that leaving power without a guarantee of immunity may result in prison time or extradition to the United States.

“The US is one of the few countries in the world that if you mess with them, they can chase you until the end of the world,” said Ferrer. “They are facing a very real danger.”

Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodriguez promised that her country would “not surrender” in a speech on Thursday at a cultural event in Caracas.

“What Venezuela is experiencing today, I would not call dangerous times, no, but rather times of historic definition, of historic insurgency, so that they know that this people will not surrender, this people cannot be blackmailed,” Rodriguez said.

David Smilde, a Venezuela expert and professor at Tulane University, told CNN that many observers underestimate how committed Maduro and his circle are to Chavismo, the socialist movement named after Hugo Chavez and the state’s guiding ideology.

“They are worried about their safety, and they are worried about their wealth,” Smilde said. “But they also think of themselves as revolutionaries, as an anti-imperialist, historically important project that has thumbed its nose at the United States, thumbed its nose at Venezuela’s dominant political class and has done their own thing now for 25 years.”

“I think that for Maduro to accept any kind of transition,” Smilde continued, “There would have to be some sort of path for Chavismo to be a viable political force, for there not to be a witch hunt for Chavistas afterwards.”

Off-ramp for Maduro

Brian Fonseca, professor at Florida International University, said that a satisfactory “off-ramp” for Maduro might be exile in Russia, but not without pressure from within his own inner circle.

“I think there has to be enough pressure mounted within the political or the military elite that ultimately push him out. I don’t think he’s going to go willfully,” Fonseca said.

On the other hand, Ferrer told CNN that he doesn’t see Maduro or his circle accepting exile.

“I don’t think they want to go into exile in Russia or Cuba or anything like that,” Ferrer said. “They want essentially something very pragmatic, where Maduro and his friends can still be the economic elite of the country, and can trust whoever’s in charge of the armed forces.”

Hold the champagne

Smilde cautioned against any hopes that the eventual end of Maduro’s presidency would signify the end of the regime.

“Because of his lack of charisma, what he’s had to do is construct this pyramid of people that are benefiting in some way,” Smilde said. “If you just take Maduro off of that pyramid, the pyramid is still there – and there’s a lot of people with a lot of interest in things continuing on the way they are.”

The professor recalled when Hugo Chavez died in 2013, many wrongly assumed that his political project had come to an end.

“I was getting on a plane to Caracas,” Smilde said. “I was walking through first class. There were all these Venezuelans sipping champagne, hugging each other, saying ‘it’s over, Chavez is dead.’ And so here we are. Nothing actually changed. That leader left, and then you had a leader that’s worse.”