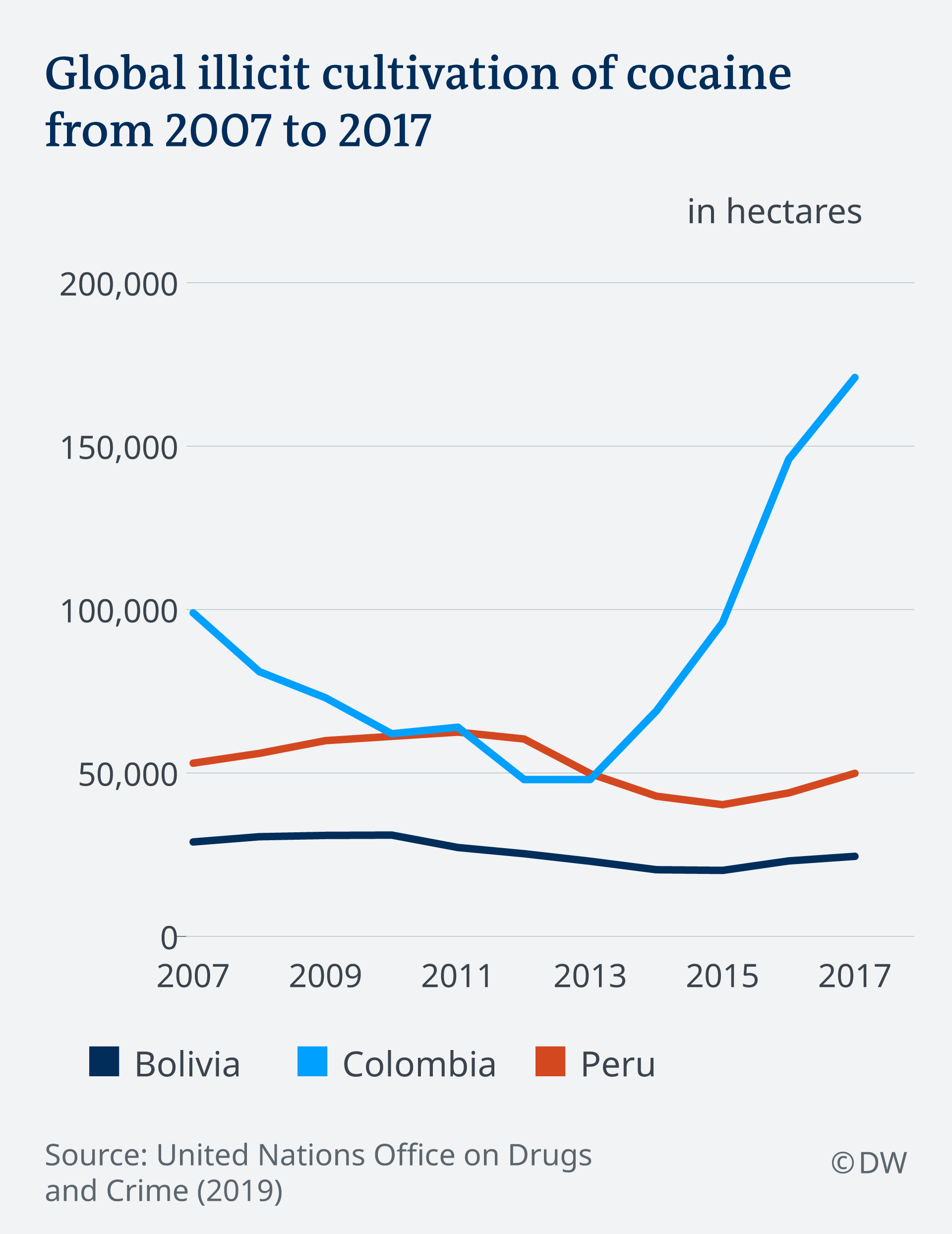

The cultivation and production of cocaine in Colombia reached record levels in 2017, according to the latest annual report from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

In its report, released Wednesday, the Vienna-based agency said Colombia’s cocaine production rose by 25% to reach a record 1,976 tons in 2017, fueled mostly by a rise in cultivation practices, which have increased from 46,000 hectares (about 113,700 acres) in 2013 to 171,000 in 2017.

Read more: Colombia’s coca growers feel left behind despite FARC deal

New figures released by the United States, meanwhile, showed that coca cultivation and cocaine production in Colombia had dropped slightly in 2018 but still remained at historically high levels. The White House Office of National Drug Control Policy said it is “working closely” with Colombian President Ivan Duque’s antinarcotics efforts to cut cultivation and drug production in half by 2023. Washington has already contributed around $10 billion (€8.8 billion) to the cause over the last two decades.

Francisco Santos, Colombia’s ambassador to the US, told The Associated Press that the 2018 figures could mean the start of a trend reversal.

“We hope to see a 20% decrease in the data about 2019 when all the things we are doing show results,” Santos said. “And in 2020 we will see an even larger reduction.”

But despite Santos’ optimism, the UNODC findings have raised many questions. Colombia signed a landmark peace agreement with the FARC rebels in 2016 that was meant to tackle this very problem. So why hasn’t it had the desired effect?

Broken promises, economic failures

According to Isabel Pereira, drug policy adviser for the Colombia-based research and advocacy organization Dejusticia, the broken promises of the 2016 peace agreement and economic realities, some of which can be traced back to 2013-2014, are pushing poor farmers to continue to rely on coca cultivation.

She told DW that economic factors, such as the devaluation of the Colombian peso in comparison to the US dollar, made exports more profitable. Additionally, the global decrease in the price of gold forced many Colombians who had traded the cultivation of cocaine for gold exploitation to go back to their old occupation.

Read more: Colombia’s cocaine: Who will take charge now?

“There is also a permanent cocaine demand from the US and Europe that has never ceased,” Pereira said.

But the 2016 peace agreement has also played its role, Pereira said, one that had to do with expectations. “The places where cocaine is cultivated in Colombia suffer from rural poverty and are largely disconnected from the state,” she explained.

In places like this there is no access to education, or roads to connect towns and enable farmers to sell their crops, she said. These communities have demanded more support from the state for decades, and the peace agreement seemed like the thing that would finally deliver that support.

In 2015, it was revealed that the accord would bring with it not only subsidies but also technical assistance to certain areas, in order to implement projects to help people transition from the cultivation of illicit crops to more viable economic alternatives.

“Beyond the subsidies, the expectation was that of benefiting from that targeted attention,” Pereira said.

Read more: Helping victims of Colombia’s conflict tell their stories

Weak implementation

But after the peace agreement was signed by former President Juan Manuel Santos and began to be implemented by his successor, Ivan Duque, it became clear that it was failing to achieve these ambitious goals.

“Santos’ government did not leave the adequate financing or the technical capabilities in place for the agriculture crop substitution program, and Duque’s government has not worked on continuity,” Pereira said.

Farmers who have given up their coca cultivation, only to realize they are unable to find an alternative way to make a living, are going back to their old trade and once again becoming vulnerable to coercion from armed groups seeking to gain control over the cocaine business that the FARC lost.

Pereira said that after the agreement was signed, the Santos government should have delivered more quickly on the promises it made to farmers. Instead, implementation has been too slow and unequal.

“This situation has intensified with the new government because there is no clear commitment to maintain the program’s capability and there are many changes in terms of who should be in charge of it and where the money will come from,” Pereira said.

By not giving farmers the help they need to make the transition, Pereira believes the Duque administration is actively weakening the 2016 deal and threatening the possibility of a lasting peace.