For how long will artists continue “representing” the January revolution in didactic ways, pretending that their audience were neither part of the events, nor have they followed it closely on TV? It seems like it will still be a while.

“Ehna w Zorofna” — a play that plays on an Egyptian colloquial expression, meaning “It depends” — has recently opened at the Small Floating Theater in Manial. It seems to represent much of what non-commercial theater has had to offer over the past year: reducing the revolution to chants, slogans, and superficial characters, while also carrying on with the many problems Egyptian theater has been facing for decades.

Like many plays produced post-25 January, “Ehna w Zorofna” fails to offer new perspectives or readings into the events of the past year. Director Hossam Atta, unfortunately, presented “symbolic” characters like time, history, the crushed Egyptian farmer or citizen, and of course, corrupt politicians as witnesses and narrators of recent history. There is no real plot or sequence, only a perpetuation of preaching by performers who either glorify or vilify the revolution and protesters.

Citing events from Egypt’s modern history like the 1919 revolution and how Egyptians unified behind the famous “Long live the crescent and the cross” slogan is common in plays. In “Ehna w Zorofna,” it is in no way different. Although such incidents are meant to give depth and context to the plays, the way they are presented — which is very similar to badly written history school books — ends up flattening and simplifying history; and when the January revolution is tackled, it is a continuation of this long practice. Recent plays like this one, however, make sure not to make mention of the 1952 revolution or the October war, which were until recently the country’s pride, but are now considered a legacy of the Mubarak regime, whose figures are vilified and ridiculed rather than criticized.

This is not to be mistaken, however, for a real stance against injustice or a break free from censorship. There is no mention of the events that happened after the 18 days, and how complicated things became with Egypt’s ruling military junta throughout the transition period. Actors instead chant “The army. The people. One Hand” slogan, reflecting a persistent practice of self-censorship that only allows to safely criticize the past.

But, that is not the only problematic practice that continues with “Ehna w Zorofna.” The characters of the play are again presented in stereotypical light. An Egyptian intellectual, for instance, would often stand on the stage preaching void ideological slogans, while a Muslim Brother would appear hypocritical. As for a Salafi man, he has to pretentiously speak in Standard Arabic Language while standing on stage in his white gelbab and long beard. A rich man’s son is typically corrupt and spoilt, abusing his family’s influence and connections, while a poor man is naïve to the extent of stupidity. The scenes are sarcastic, but not critical or insightful in any way, allowing the audience to easily dismiss them.

This is all in spite of having a strong cast. Atta fails to make use of the experience of actor Ahmed Maher, for instance. The star simply stands on stage dragging the audience through a lengthy rhymed monologue, supposedly reflecting the hardships of a farmer or crushed citizen; one cannot really tell.

Instead of creatively playing on the many connotations of the expression: “Ehna wa Zorofna,” the director seems to have approached it in the most straightforward way. The play’s title implies skepticism and uncertainty. A literal translation would read “Us and our circumstances,” but in everyday life it means “it depends” and is sometimes used to avoid giving a clear-cut answer to a question. Atta uses it literally: “Us” being the audience and public, while “our circumstances” is meant to reflect the political, social and economic situation in Egypt using exhausted dialogues, images and performative techniques.

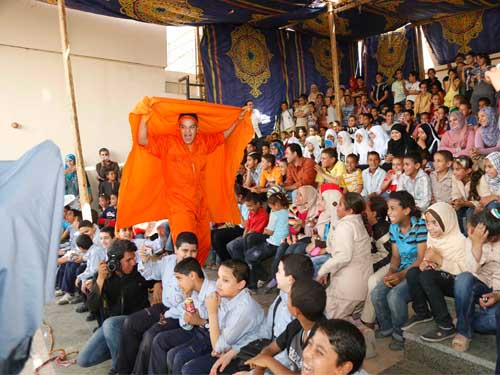

There are a number of performances with dance troupes throughout the play, yet they seem to be employed to increase playtime rather than adding to the theme or engaging the audience on an emotional level. And of course, there’s comedy and satire like the scene making fun of a couple supposedly representing “The Party of the Couch.” Most characters are similarly flat. They have no characteristic traits. In fact, one cannot tell if they come from the countryside or the main cities. They are just faceless characters in gallabeyas to be ridiculed, sadly hoping to make an audience laugh; and even in that they fail.