Farmers, electronics retailers and other US businesses are bracing for a backlash as President Donald Trump targets China for stealing American technology or pressuring US companies to hand it over.

The administration is expected Thursday to slap trade sanctions on China, perhaps including restrictions on Chinese investment and tariffs on as much as $60 billion worth of Chinese products.

Dozens of industry groups sent a letter last weekend to Trump warning that “the imposition of sweeping tariffs would trigger a chain reaction of negative consequences for the US economy, provoking retaliation; stifling US agriculture, goods, and services exports; and raising costs for businesses and consumers.”

The announcement will mark the end of a seven-month US investigation into the hardball tactics China has used to challenge US supremacy in technology, including dispatching hackers to steal commercial secrets and demanding that US companies hand over trade secrets in exchange for access to the Chinese market. The administration argues that years of negotiations with China have failed to produce results.

“It could be a watershed moment,” said Stephen Ezell, vice president of global innovation policy at the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, a think tank. “The Trump administration’s decision to go down this path is illustrative that previous strategies have not borne the hoped-for fruit.”

Business groups mostly agree that something needs to be done about China’s aggressive push in technology — but they worry that China will retaliate by targeting US exports of aircraft, soybeans and other products and start a tit-for-tat trade war of escalating sanctions between the world’s two biggest economies.

“The sanctions are a very big deal,” says Mary Lovely, a Syracuse University economist and senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “The Chinese see them as a major threat and do not want a costly trade war.”

The move against China comes just as the United States prepares to impose tariffs of 25 percent on imported steel and 10 percent on aluminum — sanctions that are meant to hit China for flooding the world with cheap steel and aluminum but will likely fall hardest on US allies like South Korea and Brazil because they ship more of the metals to the United States.

Trump campaigned on promises to bring down America’s massive trade deficit — $566 billion last year — by rewriting trade agreements and cracking down on what he called abusive commercial practices by US trading partners. But he was slow to turn rhetoric to action. In January, he imposed tariffs on imported solar panels and washing machines. Then he unveiled the steel and aluminum tariffs, saying reliance on imported metals jeopardizes US national security.

To target China, Trump has dusted off a Cold War weapon for trade disputes: Section 301 of the US Trade Act of 1974, which lets the president unilaterally impose tariffs. It was meant for a world in which large swaths of global commerce were not covered by trade agreements. With the arrival in 1995 of the World Trade Organization, which polices global trade, Section 301 fell largely into disuse.

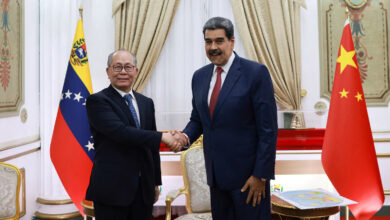

At first it looked like Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping were going to get along fine. They enjoyed an amiable summit nearly a year ago at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort in Florida. But America’s longstanding complaints about Chinese economic practices continued to simmer, and it became more and more apparent that the US investigation into China technology policies was going to end in trade sanctions.

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang this week urged Washington to act “rationally” and promised to open China up to more foreign products and investment. “China has been trying to cool things down for weeks. They have offered concessions,” Lovely says. “Nothing seems to cool the fire. I fear they will take a hard line now that their efforts have been rebuffed. … China cannot appear subservient to the US.”