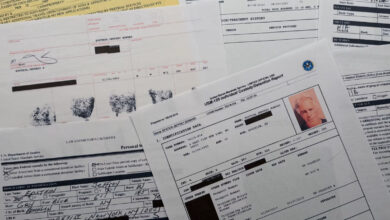

The scandal involving American billionaire Jeffrey Epstein involved more than sex trafficking and the exploitation of minors – it revealed a massive blackmail network involving figures at the highest levels of power, politics, and wealth.

The Arab public response to the scandal has largely been a collective “I told you so.”

It is viewed as a confirmation of the moral and socio-political decadence of a West that frequently lectures the world on freedom, human rights, and the protection of minorities, all while descending into the worst imaginable forms of exploitation, corruption, and systemic moral decay.

In short, the scandal has solidified a prevailing belief that the West has suffered a total moral collapse, abandoning the values of honor and integrity.

We aren’t here to debate the validity of this perception; that is for the researchers and academics. Yet a pressing question remains: where do we, as Arabs, stand in all of this? The Epstein files and correspondence have uncovered a significant Arab presence.

The documents mention Arab businessmen, officials, and prominent figures, revealing coordination for meetings between Epstein and influential Arab political personalities.

These ties spanned financial and political realms, including discussions on commercial ventures such as the issuance of an Islamic currency. In one instance, an Arab businesswoman reportedly sent four pieces of the the covering of the Holy Kaaba to Epstein, describing them in messages as items touched by millions of Muslims.

While there is no definitive proof of immoral conduct, there are indications of messages that “crossed red lines” in their tone or in comments made regarding photos of individuals.

Why were these relationships not uncovered and publicized? There may be reasons related to the state of press freedom and the absence of true investigative journalism. Legal hurdles might also prevent the dissemination of correspondence for fear of prosecution.

Yet, the more critical factor is that the very structure of Arab societies discourages delving into such practices.

When an individual or official is embroiled in a moral or corruption scandal, they often seek refuge in their “kinship network”—be it a tribe, clan, or sect. This support system views an attack on the individual as an affront to its own collective dignity; exposing corruption is perceived as a targeted strike against the group.

Indeed, many view an official who exploits his position for the benefit of his relatives as “chivalrous” or a man of duty, rather than a corrupt actor. Furthermore, we adhere to a culture of concealment; we often view the whistleblower or the leaker of information as a “snitch” intent on character assassination, rather than a virtuous citizen protecting public funds.

Sociologists argue that there is a normalization of corruption—a desensitization to it. It has become an ingrained part of our daily lives, fueled by a widespread conviction that everyone does it.

Consequently, political, financial, and moral scandals have lost their power to shock the public; the ceiling of ethical expectations for public officials has dropped significantly.

This is compounded by a culture of despair and futility. In the public eye, exposing corruption will not lead to real change. The belief persists that the corrupt individual will always slip away unscathed.

In such an environment, silence becomes the safest option.

Arab societies, like the rest of the world, have their own Epsteins who violate every value and norm. However, we erect walls of negative customs and outdated values to protect them. These Epstein-like figures—who engage in political, moral, and financial depravity—exist in the Arab world, yet they remain difficult to expose.

Even when one is uncovered or ousted, it is usually the result of internal power struggles rather than the product of legal accountability mechanisms.

Author’s bio

Abdel Allah Abdel Salam is the managing editor at Al-Ahram newspaper where he writes a daily column titled “New Horizon”.

He holds a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism from the Faculty of Mass Communication, Cairo University (1987).

He began his journalistic career at Al-Wafd newspaper, then moved to the Middle East News Agency, before settling at Al-Ahram newspaper in June 1991. He founded the Al-Ahram electronic portal and served as its editor-in-chief from 2010 to 2013.

He held the position of executive editor-in-chief of the Al-Masry Al-Youm website in 2013.

Salam has also worked as managing editor of the Al Ain (UAE) portal in 2016, and managing editor of the “Al-Watan” (Egyptian) newspaper’s website in 2017.