Today marks day four of a historic referendum in which the people of Southern Sudan cast their votes to determine whether to secede from the North. They are likely to become Africa’s newest independent nation. The date for this referendum was set six years ago, during the signing of a comprehensive peace agreement (CPA) that ended a 22-year civil war between north and south. The extraordinary voter turnout and jubilation at the polls this week reflects the desire of so many to free themselves from decades of oppression and marginalization by successive Northern-dominated regimes. After enduring a brutal war in which two million people were killed and four million more were displaced, it is clear that the people of Southern Sudan are ready to become first-class citizens of their own sovereign state.

As a northern Sudanese living in the diaspora, I am experiencing this historic moment with mixed emotions. I feel hopeful and inspired by a people who are inching closer towards their dream of self-determination. The demands of the Southern Sudanese liberation struggle represent the Sudan many of us in the North want: a nation in which wealth and power is more equitably distributed and where everyone–regardless of ethnicity, faith or gender–is treated with respect and dignity.

The impending secession of Southern Sudan should also serve as a wake-up call for us to recommit ourselves to the struggle for democratic change within our soon-to-be, newly drawn borders. The balkanization of African states can be devastating, because it makes them more vulnerable to neo-colonial exploitation and undermines their political sovereignty. So we must ask why it has come to this.

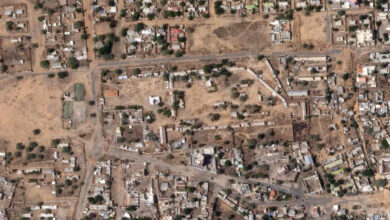

The fact is, the Sudanese government has failed to make unity a viable option for Southerners. Over the past six years, rather than making strides towards equitably sharing wealth and political power with the South, the Khartoum regime strengthened its grip at the expense of the majority of its citizens. The peripheral regions of Darfur and the South remain particularly neglected and underdeveloped.

A vote for secession will give the South control of about 80 percent of Sudan’s current oil production of 490,000 barrels a day. This will represent a drastic shift from the 50-50 share between the Sudanese government and the Government of Southern Sudan set for the interim period, following the signing of the CPA. Meanwhile, the burden of these potential losses is likely to be carried by those already marginalized in Northern Sudan. In the days leading up to this referendum for instance, the Sudanese government raised the price of fuel and sugar in preparation for the nearly projected 70 percent drop in oil revenues once the South secedes. According to economic experts, the new price increases reflect the “price of separation” from the country’s south.

These price increases have already caused suffering in the war-torn region of Darfur, where basic food items such as grains and vegetables are becoming more expensive as transportation costs rise. For the millions of Darfurians still living in the squalor of camps and dependent on food aid, an increase in fuel prices also has implications on food delivery and access to water among the displaced.

Sudan is currently sub-Saharan Africa's third-largest oil producer, behind Nigeria and Angola, providing China with 30 percent of the oil that fuels its factories. And yet very little of Sudan's oil profits have benefited its people. Instead, oil companies, primarily from China and Malaysia, have been providing the technology for oil exploration, while sharing the profits with the elites in power. Khartoum's regime is said to have siphoned off as much as 40 percent of total oil revenue, lining its own pockets through various forms of mis-pricing, instead of taking on the task of developing vast regions of the country that have been neglected for decades.

When a regime driven by greed loses its grip on power, it tends to tighten that grip before losing control. President Omar al-Bashir's latest remarks on the eve of this referendum demonstrate this tendency quite vividly. In the days leading up to the vote, he announced that were the South to secede, he would change the constitution in the North to impose Sharia law and ensure that Islam and Arabic are the official religion and language. He also declared that the 1.5 million Southern Sudanese living in the north would lose citizenship rights and be removed from all public service positions, thereby perpetuating the marginalization and exclusion Southern Sudanese people have fought against for decades.

The people of Sudan belong to over 597 ethnic groups and speak over 200 languages and dialects. Of those ethnic groups, approximately 60 percent identify as indigenous African and 40 percent as Arab. Seventy percent of Sudan is Muslim, 25 percent follow indigenous traditions and five percent are Christian. If the South secedes, these demographics will shift, but the cultural diversity and religious pluralism of the country will remain intact. People who identify as indigenous Africans and do not speak Arabic as their first language will continue to constitute a majority in the north. And while most are Muslim, many do not adhere to the practices and interpretations of Islam put forth by the ruling elite. Forcefully imposing a mono-cultural national identity is therefore a dangerous project which could potentially lead to future demands for secession.

As we witness the people of Southern Sudan cast their votes on this historic occasion, it is therefore my hope that we in the North will organize ourselves around an alternative project that recognizes our people's diversity as its strength. While the referendum represents a failure on our government's behalf to make unity a viable option, it also represents our own complicity and silence around policies that, if left unchallenged, could ultimately lead to the further fracturing of our nation. We cannot, however, rely on outsiders with a variety of agendas and motives to challenge these policies for us. It must come from within, with the support and solidarity of those who respect Sudanese sovereignty and have the best interest of all Sudanese people at heart.

Nisrin Elamin is a Northern Sudanese educator and activist living in New York City. She is the coordinator of the Support Darfur Project which documents and supports Darfurian-led grassroots initiatives and blogs at www.supportdarfur.org.