The buses come from Sharm el-Sheikh. Mercedes, Scania, Volvo — the streamlined, high-torque vehicles are parked side by side on the far side and facing the shops. The drivers stay inside their air-conditioned vehicles. The shops sell alabaster sphinxes, crystal eggs, shawls and trinkets, and the shopkeepers watch from the shade while the tour groups assemble in front of the boom gate.

Only Bedouin are allowed to drive the couple hundred meters between the boom gate and St. Catherine's Monastery, just over the hill. Drinking tea in the shade, Mohamed, 27, will drive you there for LE10. In that low-slung station wagon, the one parked over there.

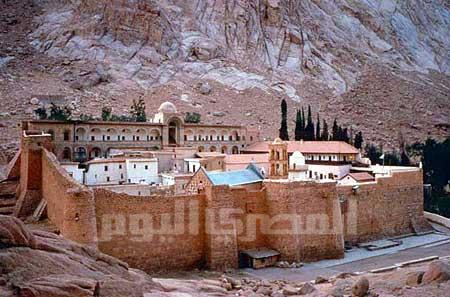

Dahab has good diving, Nuweiba is tranquil, but St. Catherine is something else. The town is situated at juncture of several wadis, or valleys. Enormous granite outcrops overlook the town, a rock climber’s dream. Venture up into the wadis and you come upon isolated gardens of pomegranate, almond, wild rose, fig and pear, all built around a natural spring. It’s cool in the shade.

St. Catherine tourism was struggling even before two Americans were kidnapped in Wadi Feiran, a large cultivated valley northwest of St. Catherine, on the bus route from Cairo in February. The mass tourism to the monastery and Mt. Sinai is doing alright. Occupancy at Sharm is meant to be around 80 percent, but tourism numbers at the monastery are down 50 percent, according to tour guides.

Still, that’s a lot better than the hit sustained by the trekking business, which has pancaked with the revolution and the violence in Sinai. Jetting into Sharm to drink imported liquors and then ride out to the monastery is one thing, but tramping about the remote and barren tribal lands is a whole other order of perceived risk.

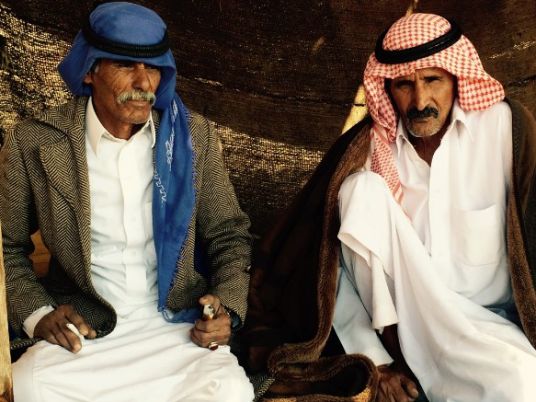

The Bedouin around St. Catherine are Jabaliya Bedouin, one of seven tribes in South Sinai. Tourism, and mainly hiking tourism, is where they get their money. Around 80 percent of the tribe’s 5,000 members are employed in tourism, mostly guiding and looking after camels, says Sheikh Mousa, who runs the Bedouin Camp guesthouse in town.

Another tribe or a single family might kidnap the tourists, but it is the Jabaliya and the businesses in Dahab and Nuweiba that suffer from the downturn.

Sheikh Mousa is keen to emphasize the area’s safety. The same day the two American women were kidnapped, he says, a delegation of the seven tribes of South Sinai met with the kidnappers and negotiated a contract. If they kidnap again, he says, they will have to pay the other tribes massive compensation.

But a paper contract is a pretty flimsy safeguard against decades of Bedouin anger and tension with the capital.

Some weeks after the Americans’ kidnapping, our Cairo-Sinai bus was stopped by a Bedouin road block. It was just on the far side of the Suez tunnel. Bedouin had laid tires on the road and set them alight. They were driving Toyota pick-ups up and down the asphalt, firing rounds into the air from Kalashnikovs with worn timber butts. The mood was not threatening — they were bringing attention to an injustice, we learned, though we never learned exactly what it was. About seven army conscripts who had been on our bus sat under the trees.

“The army will come,” said one, with a grin. “And crush them.”

But finally, after two hours, it was a fire truck that came and we were on our way.

It took just five minutes to reach the first army checkpoint.

Traveling in Sinai, there is a sense of competing powers stepping on each other's toes, yet all are trying to present a good face to the visitors. If it weren’t for the visitors, it would be easy to see how the situation could quickly deteriorate. In private the Bedouin complain about the National Parks authority. The Egyptian government harasses the Bedouin. The Jabaliya Bedouin complain about Wadi Feiran. The non-Bedouin business owners complain about the Bedouin. The Jabaliya Bedouin complain about certain Jabaliya Bedouin taking too large a cut of the tourism profits.

For years, tourism profits have been shrinking. But they are still large enough, at least for the Jabaliya, to keep a shaky peace.

At the monastery, the men who sell guide books (LE20 to LE30) as well as crystal eggs (LE5), arrive just after sunrise to catch the first trekkers descending from Mt. Sinai. Salam, a man with a weather-beaten face, blue eyes and a blue scarf, says he’s selling just a few books a month and will return to living in the mountains if business does not improve.

“Of course, we’re angry about Wadi Feiran,” Salam says of the Bedouin who kidnapped the two Americans. “These people have nothing to do with tourists.”

There are 10 Bedouin in the cramped space of the portico, selling books and eggs. But no one is buying. While we are talking, a pink plastic bag blows through the portico, like tumbleweed.

“We are not allowed to go into the courtyard,” Salam says. “You see that man there? He’s security. He will kick us out if we go in.”

Layers of security. Inside the courtyard, outside the door of the monastery proper, three plainclothes men are watching everyone who enters. Why are you writing? Who are you? One of them asks. They are policemen.

A monk ducks out of the low stone archway and peevishly requests they not smoke there.

“The doorway sucks the smoke in,” he explains.

The Jabaliya Bedouin are master grafters, often grafting a fruit-bearing species onto hardier root-stock. Water from the square-sided granite springs is gravity-fed through PVC pipes for hundreds of meters. There are falcons, ibex and the world’s smallest butterfly.

The mountains are as rich in human history as they are in seams of quartz, turquoise and semi-precious stones. The remote valleys hide the prayer-niches of long-vanished hermits. The St. Catherine monastery has not been abandoned in 17 centuries — a millennia ago it was the go-to spot for hermits. An estimated 400 lived in the surrounding mountains at any one time; many more than slept in the stone cells of the monastery itself. Their chapels, rock-arches and flights of steps remain.

For a sense of the area’s potential, you only have to look at the recent past. Before the Second Intifada of 2000, thousands of Israeli tourists would stream over the border from Eilat, Sheikh Mousa says. They were great trekkers and loved the outdoors.

“For 20 years I had no holiday,” remembers Sheikh Mousa. “Every day we had 50 camels leaving from St. Catherine on treks.”

Nowadays there are very few Israeli tourists. There are some Europeans, but Sinai is competing with Morocco and Jordan, which both have better reputations. Sheikh Mousa’s Bedouin Camp guesthouse — one of three Bedouin hostels — appears empty but for a lone Frenchman. The larger hotels down the road, by the major roundabout, appear to be closed.

Morocco and Jordan also enjoy better marketing.

“Mt. Sinai markets itself,” says Sheikh Mousa. “But we need to market the other things to do in the Sinai.”

Everywhere people are talking marketing. Among the tour guides, at the hostels, even at the shop that sells medicinal herbs.

“There is enormous potential in the area,” says a St. Katherine-based tourism operator who asks to not be named. “You could have treks between a network of gardens in the high mountains.”

Eco-tourism is a buzz word and source of hope, and there are other signs of change and innovation. The brightest colors in town belong to the facades of the new Etisalat and Vodafone shops. St. Catherine has 3G connectivity except when Bedouin cut the lines, isolating the region — an act of protest against what they see as Cairo's overbearing interference. In the last year, this has happened several times.

Bedouin Camp has just finished extensive renovations. The kitchen has a twin-steamer espresso machine. A bus now runs twice weekly to Dahab to collect backpackers.

But the problems are not skin-deep.

“Tourism development doesn’t have vision, infrastructure, coordination or support from National Parks, the tourism operator says."Bedouin have a monopoly of the work — and there is nothing wrong with that — it’s just the management isn’t inspired. This discourages possible development. There is a stranglehold of various power brokers.”

The power brokers he identifies are the Jabaliya Bedouin, National Parks and the Sharm el-Sheikh resorts. During the Mubarak era, he said, tourism operators felt the regime discouraged tourism to St. Catherine because it would take tourists from Sharm, where membersof the Mubarak regime had financial interests. But among the Jabaliya Bedouin there are also internecine grievances.

The 40-year-old turn system allots tourists with guides. It is designed to share the business evenly, but it also means that a return tourist is unlikely to receive the same guide, even if they request. Or they will have to pay double — pay the allotted guide to stay at home, and pay their chosen guide to go with them. It’s a system that works fine when there is lots of business, but it does not reward the better guides or encourage tourists to build a relationship with the area and to return. It also means that all hiking business is funneled through a single administrative office, raising suspicions that a few will skim the profits.

“When we went to speak to the man at Wadi Feiran,” says Sheikh Mousa’s business associate, Saleh Mousa, “the man said, what has the government done for you? Where is the good hospital? Where are the schools? National Parks takes US$3 from each tourist who comes into the protectorate, but where does the money go?”

The money that is being spent seems to be going to the wrong projects. A streetlight project has clogged the village’s streets with hundreds of sodium lamps, which most Bedouin seem to hate. A pipeline bringing water from the Nile was recently completed, but the municipal street plumbing is broken and the water remains untapped in the tank on the hill.

“We use jerrycans,” says Sheikh Mousa.

National Parks has placed trash bins on the route up Mt. Sinai. But the wind just gets in and blows the rubbish away. The parking lot of the magnificent five-building Visitors Center is permanently closed. It has become a soccer field for the kids that live across the road in cinderblock housing. There are no road signs.

In six months, says Mohamed Kamel, a National Parks environmental researcher, the parking lot will be opened and the buses will stop here, instead of up at the boom gate. From here the tourists will take camels to the monastery.

Up at the boom gate I ask the proprietor of Mt. Sinai Restaurant & Services what he thinks of the parking lot plan, which will likely put him out of business.

But he appears surprisingly unworried. He shakes his head.

“I do not think this will work,” he says.