After a catastrophic fire five years ago, the Notre Dame Cathedral de Paris reopened this month looking almost the same as it did when it was first constructed in 1163.

The massive reconstruction project was a testament not just to the hard work of the French people – but also to the lasers, drones and other advanced technology that gave rebuilders a window into the building’s past.

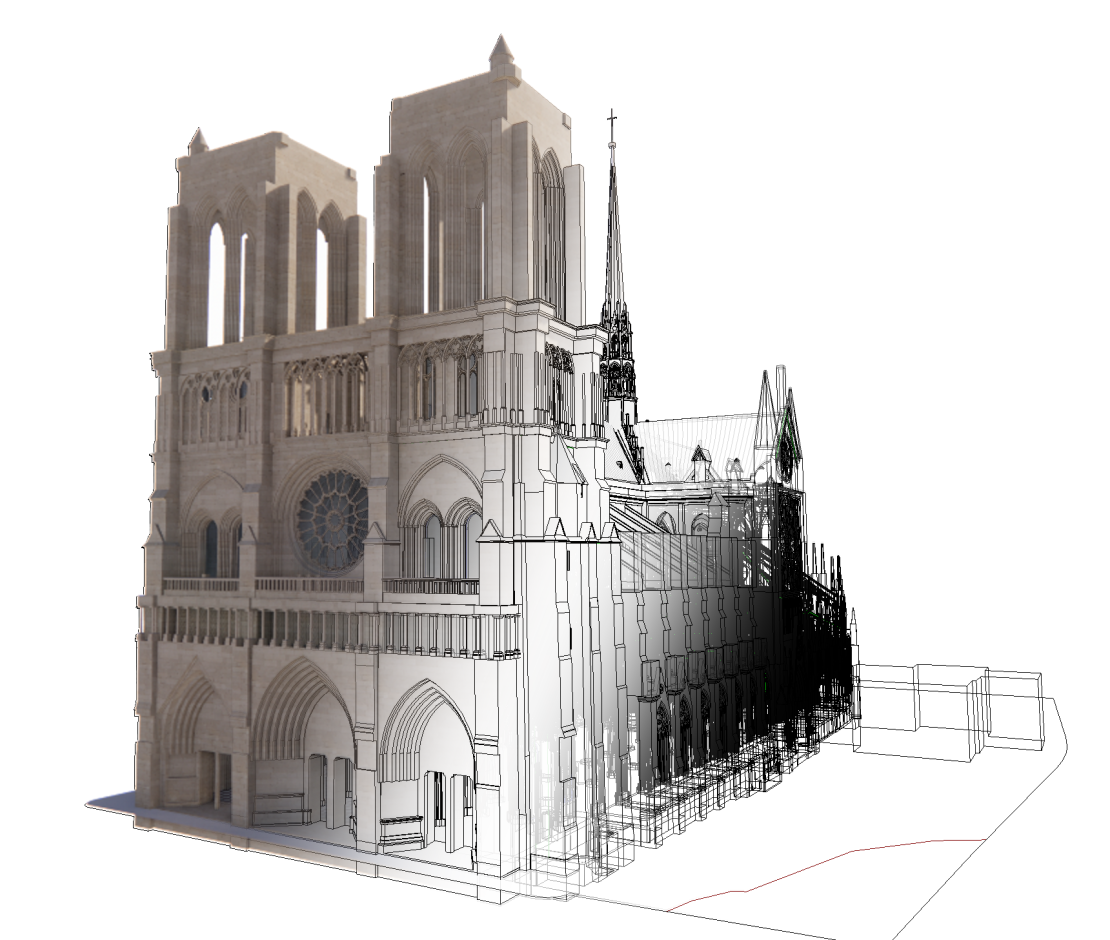

“The time frame wouldn’t have been possible without the record of what existed,” Amy Bunszel, executive vice president of architecture, engineering and construction at 3D-software company Autodesk, told CNN. Her company was a major part of creating a model of the building as it existed before the fire, giving the reconstruction effort a sort of guide for what to do. “It would’ve required a lot more guesswork. Imagine taking millions of tourist photographs (as a reference point) versus having one consolidated perfect representation.”

The technology allowed France to meet President Emmanuel Macron’s ambitious five-year goal for rebuilding the landmark. It took teams at several companies combining rounds of damage assessments, specially created maps and advanced techniques that are now used in everything from film animation to construction.

And it took a little luck, too.

A billion points of lasers

The reconstruction, in one sense, started even before the fire. In a stroke of luck, in 2015, art historian Andrew Tallon carefully scanned the building with lasers. Tallon, who studied Gothic architecture, was trying to understand how medieval builders erected some of Europe’s great cathedrals.

His initial effort – four years before flames engulfed the cathedral – required 12 lasers and a team of seven engineers to scan the building and collect 46,000 images, according to Bunszel. The spatial map he created used more than a billion laser-measured points, and he revealed some previously unknown details about the cathedral – like how the interior columns at the western end of the cathedral do not line up.

Tallon died in 2018, just months before the April 2019 fire that shocked Paris. By the time hundreds of firefighters put out the flames, most of the structure had been destroyed, including the iconic 315-foot spire, which collapsed through the roof.

While his detailed scans revealed much about the ancient structure – which has been through countless modifications and smaller changes through the centuries – they were, by themselves, not enough to build the kind of detailed model that would be needed to restore Notre Dame.

That’s where Autodesk stepped in. After the fire, Autodesk worked with French laser firm AGP to install scanners around the cathedral and capture billions of points that were needed to create a full-scale digital model. The companies donated their services to Rebâtir Notre Dame, the public institution that led the restoration efforts.

The post-fire process wasn’t always smooth, Bunszel said.

“The cathedral was very unstable right after the fire,” Bunszel said. “They had to build temporary structures and continuously scan during the rebuilding process.”

Recreating history

Ultimately, the complete view was captured by layering new laser scans and drone footage with Tallon’s previous scans.

Because of the complexity, structural details and size of Notre Dame, it took the companies over a year to create the newer 3D model. Compared to traditional methods of documenting historical structures, these types of scans dramatically accelerate the process. Notre Dame required ongoing scanning as well.

Although the new cathedral looks nearly identical to the original, a few areas were modernized: the addition of sprinkler and fire suppression systems, optimized lighting placement and a cleaner appearance thanks to years of less soot from candle use and operation.

The plaza outside the cathedral was also redesigned with the help of Autodesk’s technology. The company supported four competing teams to create 3D visualizations of their proposals before they received public input, and a winner was ultimately picked.

Autodesk, founded in 1982, has a long history in using 2D and 3D modeling for everything from film animation and video games to construction. Its scanning technology has played a key role particularly in disaster recovery and historic preservation. After a major earthquake damaged Christchurch, New Zealand’s cathedral in 2011, its technology helped rebuild the structure with drones and a robotic dog – equipped with a mounted laser – used to scan unsafe areas.

In the US, the same technology helped create a digital replica of the Michigan State Capitol and historic downtown of Brownsville, Pennsylvania, to support preservation efforts.

Wladek Fuchs, a professor of architecture and community development at the University of Detroit Mercy, believes more governments and institutions should consider scanning buildings in the event of a tragedy or natural disaster. He’s currently involved with a project to reconstruct the ancient city of Volterra, Italy, with 3D modeling in partnership with the Digital Preservation Workshop of the Volterra-Detroit Foundation.

“Disasters strike in unexpected places, but if the most precious structures of our cultural heritage can be documented this way, the effects will be less devastating,” he said.

For Notre Dame Cathedral, the latest 3D model is not only as a way to honor the past, but also an investment that will pay dividends for years to come.

“Going forward they have a 3D representation of the building they can use for maintenance,” Bunszel said, “as well as plan for the future.”

Michelle Lou and Brandon Griggs contributed reporting.