“Don’t believe everything you hear, even what I am telling you,” one of the narrators says. It is a classic storyteller move — reminding the listener to always doubt a little. This is after all a story told only from one perspective. And the narrator is not omniscient.

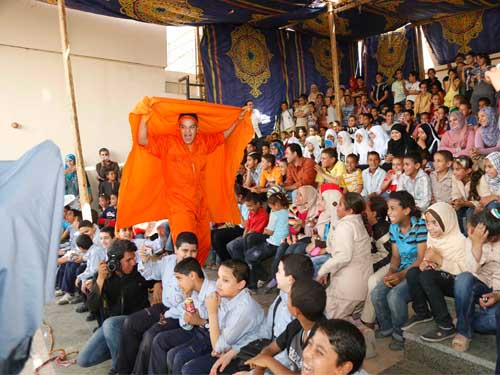

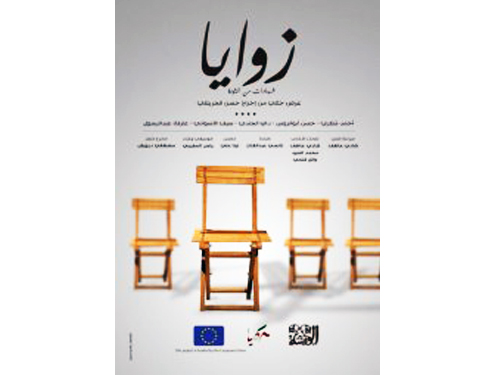

“Zawaya — testimonies from the revolution” put together by independent theater troupe Al-Warsha, and showing again this weekend, is made up of five narratives.

While these stories are mostly anchored in the 18 days, they do not hark back to the hope or unity of that moment. They are not reminiscing stories. Rather, they are invitations to reflect. For director Hassan al-Geretly, it is about “meditating on the stories.”

Recorded long after the 18 days, some of them over several months, Geretly worked with writer Shadi Atef on the five testimonies. In between each narrative, there is oud playing and a song that sings of the revolution.

“The idealism of the 18 days remains a kind of reference,” says Geretly. “But there is ambiguity, not simple celebration.”

Indeed, most of what focuses on those 18 days is charged with strong and difficult emotions. In the final narrative, the mother of Ahmed, a 17-year-old who was martyred, says she does not want the person who shot her son, or the officer in charge that day, to be held responsible. Rather, it was the man who gave the order, Interior Minister Habib al-Adly. This continued naming of the responsible in public places has a resounding power and points to an ongoing struggle against the devaluation of human life by security services that started before 25 January and continues well beyond it.

The stories we neither listen to nor tell

While there are narratives from the mother of a martyr and a member of Ultras Ahlawy, there is also the narrative of the army officer and the paid thug. At its most basic, “Zawaya” is a reminder that there are different ways of being involved, being shaped, remembering and telling the revolution.

“It is about reality being multiple,” Geretly says. “There are multiple points of view, and these are the stories that we tend to neither listen to nor tell.”

That’s why it’s called “Zawaya” — angles.

“People have their reasons even if we don’t agree,” Geretly says simply. He explains that in this, he always thinks of playwright Anton Chekov for whom “each character has its own logic.” Indeed, while none of the “Zawaya” narratives are privileged over others, it is clear where the commitment of the production lies.

By chance, at a meeting with friends Atef, who wrote much of the performance, met an army officer, and spoke with him for a few hours. He wrote out a narrative and got in touch with him. After reading the text the officer requested a few changes, for instance the altering of details that might make him identifiable — “This is my salary,” he had explained to Atef. The process of collecting the other narratives took place over several meetings. In the case of the Ultras member, he was a friend of Atef. What he witnessed and experienced at Port Said had devastated him — the person next to him had been killed — and most meetings, Atef says, involved tears. He had wanted not a single word of his narrative changed.

The challenge was, in a sense, to balance concerns of art with the fact of the narratives’ historicity. “We are living through historical times, and these are historical documents,” Atef says. When he was writing and editing, he sought to make sure the different aspects of the personality were present, and to maintain, and even bring out, the “internal music” of these narratives. But in terms of heavily interfering, “I would have felt I was exploiting them. Humanly, it was not possible to do that.”

The “thug” narrative is in fact an amalgamation of six different stories, and the name given to the character who speaks the narrative is that of one killed in a personal feud in the early days of the revolution. Atef then took the stories of the remaining five, and blended them together. One of them worked with the actor, Atef instructing the actor to pay attention to how he spoke and to his manner.

From a working-class neighborhood, Atef knew the men. Each spoke, linking seemingly disparate things together, and there was something chaotic about it, he says. What was interesting though, Atef felt, was them asserting their presence. They talked about the 18 days, and all the major events since, asserting their role in them — this, and the chaotic way of thinking, are reflected in the final text.

In the narrative, the “criminal” asserts that he was in Tahrir Square for 11 days, and the remaining days part of a popular committee in the neighborhood. Atef thinks the one who told him this wanted to assert that he was in the square throughout, but knowing that Atef had seen him in the neighborhood, could not. In the narrative, the narrator talks about seeing people take money to chant in favor of Mubarak and attack protesters. Atef knows, however, that actually he did not see them; he was one of them. The form of storytelling has a strong and yet ambiguous relationship to “truth,” history and art.

The character asserts again and again that he is reformed — he no longer steals or breaks the law. But he also locates the source of his wisdom in his criminal street experience. This tension, Atef said, was present in the case of all five. What comes across most in the narrative is this effort to assert himself as someone knowledgeable, as someone whose knowledge and experience cannot be discounted by society, and as a participant.

The army officer lives and works in Suez where, Atef explains, violations were committed less by the military than by the police in the period following Mubarak’s fall when the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces was managing the country. Repeatedly throughout his narrative, he describes the then-ruling military council as “treasonous” and “treacherous.” Atef explains that the officer wanted to distance himself from the actions of the military council. He would even come home to find his wife watching television, increasingly critical of the SCAF. And so, he attempts to make himself clean from their crimes.

It was a sensitive moment, Atef says, when it was pointed out to the officer that some people from within the army did take a position, referring to the 8 April officers who remain imprisoned since 2011. The officer’s response made it into the final text: those officers were stupid, because “being right is not enough, you also need wisdom and good sense.”

In this way, the officer distances himself from the military council and their crimes, as well as providing himself with a justification for not naming them as crimes. And he protects his job: “Don’t believe everything you hear, even what I am telling you,” he says toward the end of his narrative. A comment not just on storytelling, here he implies that even he would not swear by the truth of his own narrative — you cannot hold him to his word.

Popular memory

In a sense, these stories are repositories of popular memory. In the narrative about the events of Port Said in February 2012, which left over 70 Ultras Ahlawy dead, we hear not just the anger and the horror. We hear also about the calmness, the disbelief, the numbness, and the details of the moment. This is also what storytelling offers, an attention to detail, a sort of return to the lived experience.

The narrative ends with blaming security services for the massacre, as many revolutionaries do. But he also blames the Masry Ultras, as the Ultras Ahlawy do. But the latter tends to be elided in many revolutionary narratives that do not themselves come from the Ultras. These narratives of popular memory thus pull against the streamlining and enveloping of stories to fit with the concerns of a larger narrative.

In the account of a woman visiting a hospital on 29 January 2011 in Alexandria, the narrator makes sure to remember and articulate the names of the dead that she saw that day. This belaboring of the names, as she looks to the side grasping for the full name, is a reminder: we must remember.

A woman with large calm eyes tugs at Alia’s sleeve, beckoning her to come. The woman had already told her that her son was dead, but as she takes her to him, she tries to wake him as if he were sleeping. Eventually, Alia says to her, “Your son has died a martyr.” She then doubts herself, as she is not sure if this is a revolution for him to be a martyr.

And in this sentence, she points to the significance of revolution narratives. For the meaning of the death of a son derives not only from the details of his life, but also the broader thing of which they are a part: revolution. People make meaning and struggle to come to terms with the loss they have experienced over the past two years, in part by relating their loss to a larger story, the story of a revolution that looks forward to bread, freedom and social justice.

The Ultras member came to the performance last week. His narrative was first. Emotionally overwhelmed and moved by the audience’s reactions, he left before the end of the performance. He later said to Atef that initially he hadn’t understood why his narrative had been collected, but now he did: “so that people do not forget.”

Performances of “Zawaya — testimonies from the revolution” will be held 27-30 December at 8 pm at Al-Warsha Theater Group Premises, Apartment 8, 17 Sherif Street, downtown, Cairo.