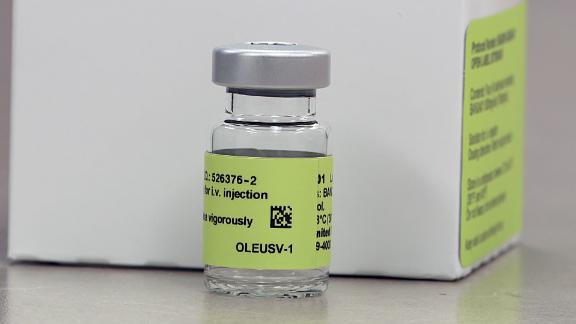

The US Food and Drug Administration granted accelerated approval Friday for the Alzheimer’s disease drug lecanemab, one of the first experimental dementia drugs to appear to slow the progression of cognitive decline.

“Alzheimer’s disease immeasurably incapacitates the lives of those who suffer from it and has devastating effects on their loved ones,” Dr. Billy Dunn, director of the Office of Neuroscience in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement. “This treatment option is the latest therapy to target and affect the underlying disease process of Alzheimer’s, instead of only treating the symptoms of the disease.”

Lecanemab will be marketed as Leqembi, the FDA statement said. It has shown “potential” as an Alzheimer’s disease treatment by appearing to slow progression, according to Phase 3 trial results, but it has raised safety concerns due to its association with certain serious adverse events, including brain swelling and bleeding.

In July, the FDA accepted Eisai’s Biologics License Application for lecanemab under the accelerated approval pathway and granted the drug priority review, according to the company. The accelerated approval program allows for earlier approval of medications that treat serious conditions and “fill an unmet medical need” while the drugs continue to be studied in larger and longer trials.

If those trials confirm that the drug provides a clinical benefit, the FDA could grant traditional approval. But if the confirmatory trial does not show benefit, the FDA has the regulatory procedures that could lead to taking the drug off the market.

What is known about lecanemab

Lecanemab, a monoclonal antibody, is not a cure but works by binding to amyloid beta, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. In late November, results from an 18-month Phase 3 clinical trial published in The New England Journal of Medicine showed that lecanemab “reduced markers of amyloid in early Alzheimer’s disease and resulted in moderately less decline on measures of cognition and function than placebo at 18 months but was associated with adverse events.”

The results also showed that about 6.9% of the trial participants given lecanemab, as an intravenous infusion, discontinued the trial due to adverse events, compared with 2.9% of those given a placebo. Overall, there were serious adverse events in 14% of the lecanemab group and 11.3% of the placebo group.

The most common adverse events in the lecanemab group were reactions to the intravenous infusions and abnormalities on their MRIs, such as brain swelling and bleeding called amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, or ARIA, which can become life-threatening.

Some people who get ARIA may not have symptoms, but it can occasionally lead to hospitalization or lasting impairment. And the frequency of ARIA appeared to be higher in people who had a gene called APOE4, which can raise the risk of Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias. ARIA “were numerically less common” among APOE4 noncarriers, the study showed.

The drug’s prescribing information carries a warning about ARIA, the FDA says.

The trial results also showed that about 0.7% of participants in the lecanemab group and 0.8% of those in the placebo group died, corresponding to six deaths in the lecanemab group and seven in the placebo group.

The Alzheimer’s Association welcomed Friday’s decision.

“By slowing progression of the disease when taken in the early stages of Alzheimer’s, individuals will have more time to participate in daily life and live independently,” President and CEO Joanne Pike said. “This could mean more months of recognizing their spouse, children and grandchildren. This could also mean more time for a person to drive safely, accurately and promptly take care of family finances, and participate fully in hobbies and interests.”

More than 6.5 million people in the United States live with Alzheimer’s disease, according to the Alzheimer’s Association, and that number is expected to grow to 13.8 million by 2060.

Will Medicare cover it?

Lecanemab will carry a wholesale price of $26,500 per patient per year, the drug’s manufacturers announced Friday.

Biogen and Eisai have listed the drug slightly below the reduced price of the Alzheimer’s medication Aduhelm, which now costs an average patient about $28,200. The companies had to lower the cost of Aduhelm – originally set at $56,000 per patient per year – after insurers balked at covering it.

In justifying the cost of Leqembi, the companies said in a news release that based on the estimated quality of life gained by people who take it, the value of the medication to society is around $37,000 a year, but they chose to go lower “aiming to promote broader patient access, reduce overall financial burden, and support health system sustainability.”

The wholesale cost of a drug is akin to a car’s sticker price. It isn’t necessarily what patients will pay after insurance or other discounts are factored in.

Insurance coverage for this medication is not a given, however. Medicare restricted its coverage of lecanemab’s sister drug, Aduhelm, after clinical trials showed questionable benefits to patients. The agency agreed to cover the drug only for people enrolled in registered clinical trials, which limited access to the medication.

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure said after the FDA’s decision Friday that her office would quickly review Leqembi, but for now, because of its accelerated approval, it will be covered the same way Aduhelm is covered.

“At CMS, we will continue to expeditiously review the data on these products as they become available and are committed to timely access to treatments, including drugs, that improve clinically meaningful outcomes,” Brooks-LaSure said in a statement.

Last month, the Alzheimer’s Association filed a formal request asking CMS to provide “full and unrestricted coverage” Alzheimer’s treatments approved by the FDA.

“What the FDA did today in granting accelerated approval to Leqembi was the right decision. But what CMS is doing by severely restricting coverage for approved treatments is unprecedented and wrong,” Pike said in a statement Friday.

“The FDA carefully reviewed the evidence for Leqembi before granting approval. CMS, in sharp contrast, denied coverage for Leqembi months ago before it had even reviewed this drug’s evidence. CMS has never done this before for any drug, and it is clearly harmful and unfair to those with Alzheimer’s. Without access to and coverage of this treatment and others in its class, people are losing days, weeks, months – memories, skills and independence. They’re losing time.”

CMS told CNN that it will review and respond to the association’s request. The agency also noted that it continues to stay informed about ongoing clinical trials, including the most recent lecanemab results published in the New England Journal of Medicine. Also, it has met with drugmakers to learn about their efforts since CMS’s coverage decision was announced.

The FDA approved Aduhelm for early phases of Alzheimer’s disease in 2021 – but that decision has been shrouded in controversy as a congressional investigation found last week that the FDA’s “atypical collaboration” to approve the high-priced drug was “rife with irregularities.”

Before Aduhelm, the FDA had not approved a novel therapy for the condition since 2003.

Aduhelm’s FDA approval and initial hefty price tag hit Medicare’s Part B premiums, driving up the 2022 standard monthly payments by 14.5% to $170.10.

About $10 of the premium spike – or just under half the amount – was due to Aduhelm, a CMS official told CNN in late 2021.

The premium increase was set before Medicare announced its limited coverage of the drug, but its actuaries had to make sure that the program had sufficient funding in case Aduhelm was covered.

Medicare’s decision, as well as Biogen’s slashing of the drug’s cost, prompted a decline in monthly premiums for 2023 to $164.90.

‘This drug is not for everyone’

The FDA’s accelerated approval of lecanemab was expected, said Dr. Richard Isaacson, director of the Alzheimer’s Prevention Clinic in the Center for Brain Health at Florida Atlantic University’s Schmidt College of Medicine.

Isaacson said lecanemab can be “another tool” in his toolbox to fight Alzheimer’s disease.

“I will prescribe this drug in the right person, at the right dose and in a very carefully monitored way, but this drug is not for everyone,” he said.

“I would do genetic testing for APOE4 first. I would have a frank discussion with my patients,” he said. “If someone is having side effects, if someone is on a blood-thinning medication, if someone has a problem, they need to discuss this with the treating physician, and they need to seek medical attention immediately.”

CNN’s Tami Luhby contributed to this report.