The southwest tremors of the Kalkan earthquake felt in Cairo on Monday were feeble compared to those of 1992. But fear of reliving the catastrophe must have crossed the minds of many. For the residents of Hattaba neighborhood in the hills of Cairo's Muqattam district, the 1992 earthquake is not only a bad memory: they still live the consequences of the 20 years of institutional failure and unfulfilled promises that followed the natural disaster. Over the years, hundreds of families have been forcibly relocated some 40 km away, in the middle of the desert. Those who are left remain unsure about the future of their neighborhood and if the state and private real-estate companies will turn it into one more inaccessible, upscale residential complex.

The plight of the Hattaba community is one of the main subjects of “Egyptian Urban Action,” an exhibition hosted by the AWAN Contemporary Art Space in downtown Cairo. The exhibition and accompanying events are entirely curated by architect, urban planner and researcher Omnia Khalil.

Using an excessively didactic approach with an explicit activist slant, Khalil chose to narrate the daily challenges of Cairo’s “informal settlements” through the voices of their people.

“They are the real experts on those issues and their voices should be heard,” Khalil told Egypt Independent.

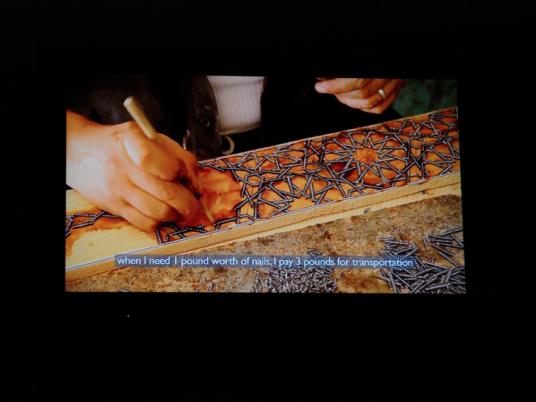

Rather than presenting a multimedia installation or displaying artwork broadly inspired by urban issues, “Egyptian Urban Action” acts more as a temporary platform for sharing knowledge and expertise, expressed through and translated into different forms and languages. Khalil uses colorful maps, photos, graphic elaborations and a looped screening of three short documentaries to convey quite a straightforward message: Cairo’s informal settlements need planning, and urban deterioration can be solved through participatory development approaches.

The show revives the ongoing debate about the different roles — often in conflict — of state actors, companies, professionals, organizations and urban dwellers in dealing with the future of their built environment, be it newly constructed or heritage. It can also be described as an advocacy campaign for specific perspectives on urban “problems” and proposed solutions.

The issues tackled in “Egyptian Urban Action,” however, are not as simple and straightforward as suggested by the exhibition; and the many solutions proposed by different stakeholders often generate controversies that can polarize and sterilize the debate. For example, street vendors and informal commercial activities in public spaces are described as a problem in need of “fixing,” while many argue that regulating these practices will be just another attempt to impose limits on spontaneous human activities in the urban context.

According to Khalil, problems such as pollution, traffic, mismanagement of natural resources, and inadequate infrastructure need to be eradicated through the contribution of different social groups with the help of professionals. “I want to help my community, I do not want to go and design skyscrapers in the Gulf,” says Khalil, showing a diagram highlighting the fact that only 4 percent of Cairo’s registered architects actually work for the city’s residents. Much of the remaining 96 percent are employed by big companies that keep them busy designing new towns and residential complexes that will sprout in the middle of the desert in Egypt and elsewhere.

Since the January revolution began, many of Cairo’s architects, urban planners and students have shown greater interest in exploring alternative approaches to urban issues that imply a closer involvement in society. Recent initiatives include advocacy groups, editorial projects, networks, local committees and initiatives for new models of management of public spaces, such as Megawra, Cairo Observer, Cairo Divided, Midan and a shadow Ministry of Housing and Urban Development. Indeed, Egyptian Urban Action, a project supported by the British Council, is only the latest on the list.

“With the revolution, my colleagues and I have experienced, for the first time, the feeling of having an impact and this has changed our attitude, work and practice” Khalil explains. “We [started] using different tools: we write reports, use social media and video, raise awareness, organize panels with people who work in the field, and we document and publish our assessments.”

For now, Khalil’s project targets the Cairene upper middle class, but she believes that Egyptian Urban Action should work inside communities and involve them to set up more local exhibitions and organize workshops with architects and lawyers.

The project’s first event was welcomed with enthusiasm — for more than two hours, architects and professors Lina Suhair and Khalil Shaath kept the audience interested despite the heat with an entertaining and accessible lecture interrupted by a poetry recital inspired by love for the city. The next lecture will take place on 15 July and will focus on case studies of the negative effects of government policies on the livelihood of informal settlements’ residents, debated by a group of lawyers.

The latest urban initiatives born in Cairo often attempt to merge different disciplines, resulting in unexpected (sometimes forced) combinations. The level of public participation is, however, always significant. Art seems to be, again, the preferred and accessible language for embracing a topic too broad to be tackled only through specialized terminology — it is used engage a larger public and non-specialized audience.

Initiatives like Egyptian Urban Action also speak about reconsidering the role of architects. “Professionals working with governmental institutions and big companies think that they can solve those problems from their office,” says Khalil.

“Because you are an architect and can draw a line, it does not mean that this line is the solution. Across the lines that architects, engineers, developers, and ministers draw, there are people. And they are the priority.”

“Egyptian Urban Action” can be seen until 19 July at AWAN Contemporary Art Space, 4 Hoda Shaarawi St., downtown Cairo.