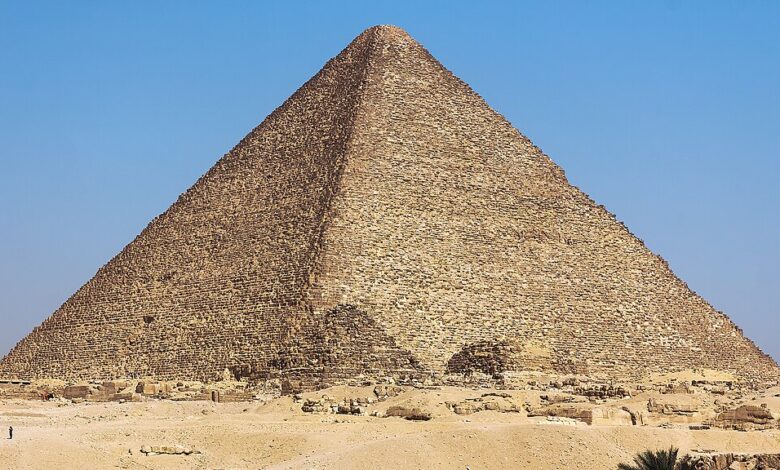

The sheer scale, symmetrical construction, and eternal steadfastness of King Khufu’s Pyramid on the Giza Plateau were the first things to capture the imagination of travelers—from the Greeks and Romans to the Arabs who followed.

Their fascination occurred even without the knowledge of the exquisite engineering marvels hidden within its design or the precise orientation of its angles – details which have only just begun to emerge through a long series of scientific studies conducted since the beginning of the 20th century.

To this day, many secrets of this miraculous structure remain unknown, and it may take centuries of future research to fully uncover the mysteries of Khufu’s Pyramid.

An ancient Egyptian engineer, utilizing the skills of the greatest astronomers of King Khufu’s time, managed to align the pyramid’s northern entrance almost perfectly toward the North Star, with negligible deviation.

In the previous article, we attempted to explain the stellar method used to determine the four cardinal directions of the pyramid.

Today, we present another technique used to determine True North, relying on the sun rather than the stars.

This method involves using a long rod placed vertically on the ground. Its vertical position is expertly fixed using a measuring instrument. The length of the rod’s shadow is measured approximately three hours before noon. A circle is then drawn on the ground using the length of that shadow, with the rod acting as the circle’s center.

Three hours after noon, the shadow of the sun is measured once again.

A second circle, equal in radius to the length of this second shadow, is drawn, intersecting the first circle. By connecting the points where the two shadow lines intersect, the direction of True North can be ascertained.

This process would be repeated over several days to ensure the accuracy of the measurements and timings.

This solar theory was likely less precise than the stellar (star-based) method explained previously. Furthermore, it fails to account for the minute directional deviations observed during the period of the Old Kingdom.

The initiation of the pyramid’s construction, specifically the laying of its foundation, was marked by a grand festival known as “Stretching the Cord.”

This nationwide celebration was characterized by music, dancing, and the extensive distribution of food, which included meat, honey-sweetened pastries, and fruits.

The Pharaoh himself attended this festival and played an active, ceremonial role.

Depictions show the King, accompanied by the goddess Seshat—the deity of writing and measurement (whose titles included “Mistress of the Builders”)—driving pegs into the corners of the structure and stretching the ropes around the perimeter.

Another crucial rite performed during the celebration was a sacrifice: an animal was slaughtered, cut into pieces, and distributed to the four corners of the pyramid, where the pieces were then covered with pure sand.

Offerings such as jars and small tables bearing the name of the pyramid’s owner were also presented.

It is likely that these rituals date back to very early periods of ancient Egyptian history.

Thanks to a number of papyri that survived the passage of time, we know that the ancient Egyptians possessed a high level of scientific knowledge in mathematics, enabling them to use arithmetic and geometry to achieve precise measurements. They understood the concept of the number one and were able to calculate the area of a triangle, a square, and a circle.

Therefore, their knowledge was not limited to basic principles of mathematics and geometry but extended to trigonometry and complex math.

The planning and construction of the Great Pyramid with such an extreme degree of accuracy stand as testament to this mastery.

Once the north-south axis was determined, the pyramid’s base was defined.

Evidence found around the Great Pyramid itself—as well as around the southern pyramid belonging to the Queens, located on the eastern side of Khufu’s monument—is conclusive and provides a clear idea of the engineering techniques used in the pyramid’s construction.

From this, we can infer that the initial step involved creating a north-south line spanning the length of the pyramid’s base side, most likely on the western side.

From one of the corners of this line, a square was then constructed using a perfect 90-degree angle.

Ancient Egyptian engineers employed several methods to accurately determine the 90-degree angle needed for the pyramid’s corners. These techniques included: using a square template, examples of which have been found; utilizing the principles of the Pythagorean triple (the 3:4:5 right triangle, though centuries before Pythagoras); or employing intersecting arcs.

Pits discovered along the eastern and western sides of the Great Pyramid indicate that the baseline extended beyond the actual perimeter of the foundation, which provided precise measurements for the length of each side.

It appears the architect of the Great Pyramid learned valuable lessons from the engineer Nefermaat, who built two pyramids for King Sneferu at Dahshur.

One is known as the Bent Pyramid, referencing the break in its angle near the final third of the construction, and the other as the Northern Pyramid, or the Red Pyramid.

In my view, this ingenious engineer, Nefermaat, has not received the fame and recognition he deserves, despite being arguably the most important architect in the ancient world. He was the first to build a true pyramid, transitioning from the earlier step pyramids (mastaba stacked upon mastaba).

Thanks to Nefermaat’s work, we know that the four sides of a true pyramid were meant to be perfectly equal, with an error rate of no more than a few millimeters.