Gustavo is happy that he has been able to “reset his life.” In 2007, he suffered an outbreak of schizophrenia, followed by severe depression. When he was hospitalized for psychiatric treatment at the Agudo Ávila Regional Center for Mental Health, in the city of Rosario, Santa Fe province, he thought he had hit rock bottom. He had recently returned to Argentina from Spain, where he had left a small daughter behind. He couldn’t find a job. His loneliness was devastating.

When talking about his recovery, the first thing Gustavo, 47, remembers is the emotional reunion he had with his 12-year-old daughter more than a decade later. Then he recalls his first visit, in 2011, to Casa del Paraná, a place for people suffering from mental health conditions such as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or depression. “I remember the director came up to me and said ‘You won’t be alone’,” he says. Casa del Paraná is where he managed to bounce back. Afterwards, he was able to find work in a company that sells printers. With the money he earns, he can travel to Spain to see his daughter.

Casa del Paraná was founded in Rosario in 2007 to help people with mental illnesses reintegrate into society and be able to work. It operates under the “clubhouse” model, born in the United States in 1948 when a group of patients from a psychiatric hospital opened the first center, the Fountain House, in New York. The goal was to end the social and economic isolation of people who struggle with mental issues.

In 1990, the Clubhouse International organization was created to oversee 320 houses that reach around 100,000 people in 34 countries each year.

“All the houses must comply with international standards and are reviewed every two years,” says Rita Larrañaga, director of Casa del Paraná, the first in Latin America. Since its creation, it has welcomed 155 members, all 18 years or older.

Today, Casa del Paraná has 35 active members, “17 percent of whom are also doing paid work experience,” the director says. “The idea is that members who did not have previous work experience, or who were employed years ago, can go back to work and rebuild their CV.”

Larrañaga explains that the clubhouse does not provide psychiatric treatment, but rather seeks to help men and women recover through a participatory method based on a free membership principle. Members work in the clubhouse, which highlights each one’s strengths and abilities while helping them to build strong relationships.

Photo credit: Marcelo Manera

“Our funds come from the Mental Health Department of the Municipality of Rosario, as well as from an international foundation, monthly donation campaigns, and three fundraising events that we conduct every year,” Larrañaga explains.

“Our mission is to help these people reach their full potential and be respected as co-workers, neighbors and friends,” Jorge Baldarenas, president of Casa del Paraná, says. He adds that a diagnosis does not define a person – it is just a small part of who they are.

Both Gustavo and Baldarenas underline that autonomy is the first thing that people with mental disorders lose. That is why the nonprofit works towards helping them reacquire it. That is also why each member decides when he or she is ready to leave the house.

Among Casa del Paraná’s activities, there is a social program with recreational outings; an educational program with spelling, music, mathematics and computer workshops; and an ‘employment in transition’ program, which offers members the opportunity to accept paid work outside the house and still be able to participate in clubhouse activities.

“When the house secures a paid position for the community, it makes it available to everyone so we can decide together who will get it,” the director explains, adding that each member can also count on a coordinator’s help when needed.

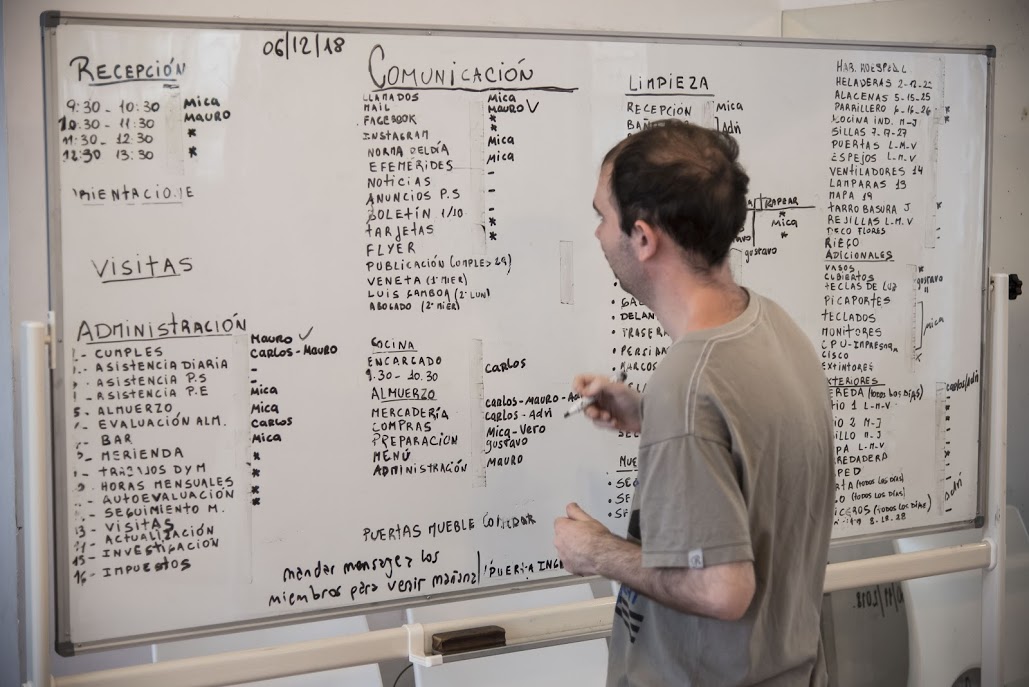

Larrañaga emphasizes the importance of having a routine. Members arrive at the house at 9 am and divide the tasks that each one will carry out during the day — some will manage the reception, while others do maintenance, cooking or cleaning. “We work on daily habits and social skills, which are often lost,” she says.

To take the initiative further, a group of professionals founded the Casaclub Foundation, based on the model of Casa del Paraná, which will launch a new clubhouse pilot project in the city of Buenos Aires, the second one in Argentina.

Beyond returning to work and feeling proud of recovering his autonomy, Gustavo says that the best thing about having taken part in Casa del Paraná was the friends he made there. “They’re my engine,” he says, “the ones who lift me up when I’m about to fall.”

Main photo credit: Marcelo Manera

This article is being published as part of 7.7 Billion, an international and collaborative initiative gathering 15 news media outlets from around the world to focus on solutions for social, economic and civic inclusion.