Han Bennink looks amazed to find himself under a bridge in Cairo. The famous Dutch drummer and multi-instrumentalist is making his first visit to Egypt. But he’s here for just 48 hours, to perform at the fourth annual Cairo Jazz Festival.

We’re sitting in the little riverbank cafe at El Sawy Culture Wheel while trucks thunder above us on the 26th July Bridge. Bennink and his agent are seated in the most secluded spot possible: any more secluded and they’d be in the river. He looks amazed to be here, but then he also has an aura of being constantly astonished. The 69-year-old has the bird-like inquisitiveness and bravura of a man flying by the seat of his pants. He also looks like he could live forever. Like some existentialist wanderer of the old school, or a traveling samurai, he rolls into town with just a kilo-weight of tools of the trade. He wears patterned tan leather boots and carries only a cheap paper bag of drumsticks.

“I used to have an incredible, huge drum kit,” he says. “But now I think that’s all show. I like to end up with an empty matchbox with two half-burned matches in it. And play with that.”

Bennink is a Dutch jazz icon, one of the central figures in the European free improvisation scene that emerged in the 1960s. His discography is just short of 200 items, but even this is said to represent only a fraction his work. This April, he will celebrate his birthday in New York “with lots of famous people.”

Like who? I ask.

“Ray Anderson, Anthony Braxton, Mark Dresser, Uri Caine, Michael Moore, Dave Douglas, Peter Evans …” They’re some of the best jazz musicians on the world circuit. The Dutchman is famous for dedication to his art, and for being the guy who once played a set on a drum kit made of cheese (yes, it’s on YouTube). Often he will scavenge bits and pieces from backstage, and incorporate them into his on-stage performance. A cardboard box. A piece of wood. Tupperware. Broken drumheads. Wooden clogs. A pizza box. A bird whistle. Whatever. Nothing is sacred.

“When I play on something, I just let the audience hear the difference between how the drum kit sounds and the garbage can. That’s the idea.”

He says he has been impressed by the Friday morning darbuka performance, which he compares favorably with marching bands in Amsterdam.

“These young people have their own rhythms that are much more advanced. Thank God I could follow it. The darbuka thing is in their genes. There’s rhythms going on we’ve probably never heard of,” Bennink says.

But he admits he has not been keeping tabs on the Egyptian music scene.

“In hippy-times, when everyone was smoking, everyone was playing Om Kalthoum. Later on I saw her in movies and she was adored by men. Really, really beautiful. That’s what I know of Egypt,” he says.

This trip is unlikely to broaden his knowledge of Egypt too much, he says. They’ve only seen the hotel. It’s very nice.

“They told me about the Cairo traffic. We’ve been to China, so I thought I knew terrible traffic. But this is a totally different traffic scene. Man! Makes me nervous,” he says.

Bennink split his year between savage bouts of travel — in which he jets between music festivals all over the world — and an isolated life in his cottage outside of Amsterdam. There, he paints and composes.

“I like to sit in my house where nobody is looking over my shoulder. I love to play, but I don’t like crowds. I feel a bit of a phobia,” he says. He has no mobile phone, no computer and no answering machine. He lives one life of travel, performance and improvisation — of beating airy sounds out of solid objects and tearing down the cardboard walls separating different schools of jazz — and another that is solitary and deeply introverted.

“With this profession of music, you never know if you still have the ability with you,” he says. “With music it’s gone in the air, whereas with painting, the walls get thicker and thicker.

The walls? I ask.

“The unsold work,” he says. “The paintings stacked against the walls. In the last 14 days,” he continues, “we spent three days in Estonia, and from Estonia had a half day home in Amsterdam, then straight to Budapest, from Hungary to Munich. And then to Rome.”

His agent interrupts: “No, you went back to Amsterdam, then we went to Turkey three days, then to Rome, then back to Amsterdam, now to Cairo. Then we will go back to Brussels for a week, then to Switzerland.”

Bennink nods. “I’m golden member frequent flyer.”

He tells a story about being “nearly arrested by a dog” that could smell the herbal residue of Amsterdam’s coffee houses on his jacket. It was at Melbourne airport — 28 hours travel from the Netherlands.

“Do you have a rotten banana in your luggage?” asked the customs officer. “No,” Bennink said. “I just smoked a spliff with my father. It’s legal in Holland.” She apologized and waved him through.

He has visited Ethiopia five times with punk band The Ex.

“I told Terrie [band guitarist Terrie Hessels), there’s no punk in Ethiopia. … But Ethiopians, boy, can they dance. We traveled deep into the south of Ethiopia playing everywhere that’s possible. The mayor of the town was very pleased to have us in a little football stadium because there was nothing to do anyway. All the people came looking at us like the monkeys we are. It’s kind of wild, man.”

“But this is quite way out, on the banks of the Nile, under the bridge. It’s so noisy anyway,” he adds.

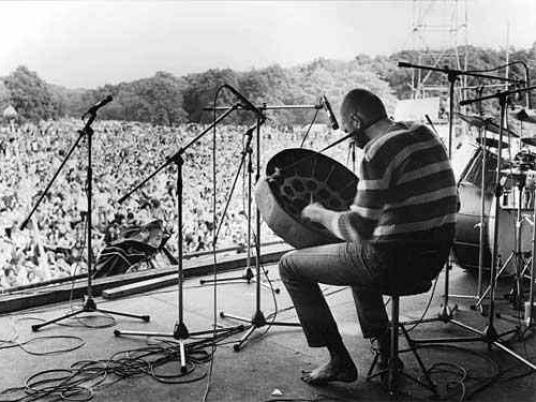

On Saturday, at 8 o’clock, he performed in the River Hall at Culture Wheel. Backstage, he looks withdrawn. He doesn’t smile. He refuses a photo, saying the show is about to start. He ties a bandana around his forehead. He doesn’t smile until the curtains open and he starts playing — a cliched drum roll that evolves into an improvised extended drum-solo, with drumsticks, drum brushes and then open palms. He stands, pops a drumstick in his mouth, and plays thwacking on the drumstick, his hollow mouth turned into a sounding board. Strange animal cries rise out of his throat. This is in the first two minutes of the show. No one has seen anything like it. In the next song a drumstick accidently slips out of his hand and cartwheels into the audience. He hurls the other drumstick after it, into the packed front row. He plays with his eyes clenched shut, muttering, grimacing as though he’s trying to remember something very long and complex. Like the number pi, for instance. He finds one rhythm and abandons it after a minute. He looks dissatisfied, almost frantic. He scavenges rhythms. He plays like a hungry wolf sniffing around a campsite.

And then, during the show, something happens that seems significant, though a little inexplicable. Between songs his agent hears a cat meowing. We’ve heard it too, says one of the backstage staff, but we can’t find it. She starts to frantically open the empty cardboard boxes that had held the speakers, until at last she finds a bedraggled kitten, and she wraps it up in her coat. Through the set she nurses this kitten, looking vaguely appalled with the callous backstage staff. The set lasts just four songs, or about 45 minutes. He has a plane to catch. Someone rushes on-stage to give him a large bouquet of flowers and a clear plastic lifetime achievement award. “What an honor,” he breathes into the mic. But actually it’s funny to imagine what he will do with these new impediments. They have just doubled his flying luggage.

“Home to Amsterdam,” he says, as they leave. “Coffee shops will be open.”