The group of young army officers that seized power from King Farouk ostensibly sought to establish the new Egyptian Republic on principles of democracy, social justice and national independence. Sixty years later, a revolution erupted with similar demands, of which the descendants of those young officers have been notably less supportive.

Historians and political scientists often cite the difference between the young and ambitious officers of the 1952 military coup, who dubbed it “the blessed movement,” and the military generals ruling the country in 2011. Yet, for many of today’s revolutionaries, the 25 January uprising is about unsettling the 1952 military regime altogether, which groomed the army as the backbone and raison d’etre of the state.

Meanwhile, a changing political context has contributed to the evolution of the military junta, from liberators and state builders to a robust interest group with economic privileges of their own to protect.

A political junta

The “Free Officers” movement that led the military coup joined the army after the 1937 treaty, which gave a level of independence to Egypt, after which the country desperately needed a strong army.

“The Egyptian army back then was very small, around 30,000. The Free Officers were the first to join this army, and were very enthusiastic about the new king, who they hoped would bring independence to Egypt,” says historian Sherif Younes.

The Free Officers, Younes argues, did not belong to the ruling regime, but as Farouk disappointed them, they became closer to the political forces unrepresented in the monarchy’s parliament, such as the Muslim Brotherhood.

“That’s why the officers belonging to Wafd Party and other parliamentary powers did not join the coup. The military elite then were from outside the regime,” he added.

Moreover, the nature of the Egyptian military in 1952 shows a highly politicized military elite affected by a vibrant political sphere under the reign of the ousted king.

“Whether we agree or disagree with the regime of King Farouk, we cannot deny that the Egyptian political sphere was very rich, with very strong political parties and institutions, which affected the political views of the military officers,” says military and strategic expert Safwat al-Zayyat.

Zayyat argues that there was an atmosphere of political mobility that enabled army officers to have certain political orientations, such as officers belonging to the Wafd Party.

A state project

Meanwhile, the Free Officers came up with a state project for the first republic through their “blessed movement.”

The highly politicized military elite enacted drastic socioeconomic reforms that changed the social structure of Egyptian society, espousing a socialist line in which the state played a central role in response to the prevailing feudalist polices of the royal regime.

The coup leader, Gamal Abdel Nasser, implemented fundamental reforms to the agricultural sector by issuing the “Agricultural Reform Law,” aimed at redistributing land ownership to benefit small farmers.

He also started a wave of nationalizing privately owned companies and factories, most famous of which was the Suez Canal, in addition to building new factories for heavy industries like steel to foster national industrialization.

Moreover, granting free education to all also heralded a new era of social mobility for Egyptians.

“This was a revolution from above,” political analyst Ziad Akl argues. “The military elite used post-colonial rhetoric to challenge Western imperialist powers.”

This anti-imperial and often populist rhetoric, coupled with socially responsible policies, brought the military elite widespread popularity, with people allowing their new rulers to monopolize the political space entirely.

“After winning the support of the public, the military regime allowed protests and gatherings only to support the regime,” Younes says.

He believes that the military junta in 1952 was openly calling for “quietness and calmness” as it successfully managed to keep the masses away from the streets.

Moreover, after the success of the military coup, Zayyat argues, the political plurality inside the Egyptian army ended. “The military elite wanted to make sure that no more military officers would have the capacity to make another coup against them.”

A shift away from politics

The war years in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s took up most of the army’s attention with military matters. However, with the 1979 peace accords with Israel, that attention shifted away. Anwar Sadat adopted a conciliatory attitude towards the West and Israel. War, military activities and state building became low priorities for the army, which started to be showered with millions of US dollars in annual aid.

Camp David became an important juncture in the nature of the military institution, shifting its interests to growing economic activity. “During the times of Sadat and Hosni Mubarak, the military was granted an independent budget and a considerable part of civilian bureaucratic posts, in exchange for securing the regime while facing any political troubles,” Zayyat asserts.

This economic empire and the privileges of the army further isolated the military elite from society, particularly with the shield that the state granted to the military institution, exempting it from accounting for its expenditure and barring the media from talking about it.

Soon after Camp David, Egypt further opened up to the West through its nascent neo-liberal policies. “I think one of the major shifting points here was the end of the Cold War and the fall of the Soviet Union,” Akl argues. The army’s economic activities thrived in this context.

But Younes contends that the privileged position of the army goes back to King Farouk’s time, which has become a legacy of the modern state.

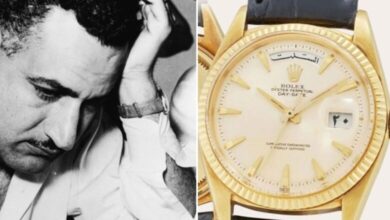

“We cannot claim that the army did not enjoy the same economic interests in 1952. I can recall the speeches of Nasser and other army officers confessing that King Farouk granted them various economic interests,” Younes says.

“Abdel Nasser, whose father was a simple post office worker used to have a car, which was unprecedented for an average citizen in 1952,” he argues.

Today, although the economic status of the average army officer in Egypt would not be that luxurious, the level of social and medical insurance provided by the military institution puts them above many impoverished Egyptians.

And above that, army generals today sit on an economic empire consisting of thousands of factories producing consumer goods, hotels, wedding salons, hospitals, clubs and more. After retirement, most of these generals hold important civilian posts in the Egyptian bureaucracy.

Meanwhile, the military elite was politically marginalized during Mubarak times as a new class of civilian, neoliberal businessmen, was groomed. Mubarak acted as the buffer between the rising businessmen and the military elite, dispensing rewards both ways to contain them. Many contend that Mubarak empowered the security apparatus to control the country’s political life, at the expense of the military elite. In fact, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, which led the transition following Mubarak’s ouster.

A return to politics

The advent of the 25 January revolution paved the way for the re-introduction of the military elite to political life.

“The equation suddenly shifted. We are now faced by a revolution of the masses against Mubarak’s regime, which the military junta is part of,” Zayyat argues, adding that the situation is made even worse by the fact that the generals are not as young as the Free Officers and enjoy no political awareness.

“It is good that the army during Mubarak’s time was not politicized,” he adds, saying that it reflected poorly on them when the country needed them politically. Many charge the ruling SCAF with mishandling the transition following Mubarak’s ouster.

While the generals stood against Mubarak, in what many observers deem as their chance to reclaim their political position in the state following decades of marginalization, they did not embrace a revolution bringing a new civilian elite to power.

“When the masses took to the streets on the revolution’s first anniversary chanting against military rule, the military junta did nothing to them. They failed to contain street action in comparison to the Free Officers. The military only confronted the revolution when the numbers were few,” Younes says.

While retuning to an active role in the political scene, today’s junta is in the process of configuring a new position in a landscape where civilians have inevitably garnered a presence.

“The military institution now is involved in the power matrix of the society,” Akl concludes.