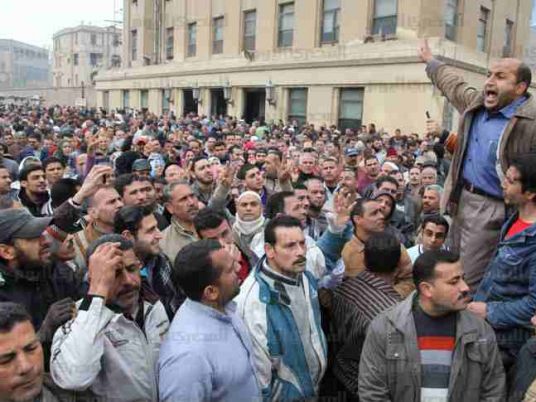

Just days before Egypt holds a major economic conference to attract foreign investors, scores of workers held the latest in a string of protests outside government offices in Cairo, complaining they had not been paid for months and accusing officials of siding with the company's investors. With some pushing and shoving, police broke up the gathering.

"This is only going to escalate," said Tarek Tabl, a 52-year-old engineer who has led negotiations with the government trying to resolve the dispute. He and his wife, who also works for the construction company, have not gotten their salaries for five months. "I'd rather kill myself than go home and face my kids," he said.

The company was among the first wave of state-owned enterprises privatized in the 1990s, when Egypt embarked on major economic reforms aimed at attracting foreign investors. Since then, the company's workforce has been cut from 8,000 to 2,000. The investors are trying to sell off assets and have idled remaining workers. "This is the kind of investment that is producing only unemployment and chaos. We are turning into ticking time bombs," Tabl said.

For many Egyptians, the experience from that era casts a shadow as the government of President Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi makes the most ambitious reforms in decades to lure foreign investors, with the conference opening Friday as a centerpiece.

Egypt needs a major injection of investment to fix an economy gutted by four years of turmoil since the 2011 uprising. This time, the government is offering around 50 major new projects for investors. Investment Minister Ashraf Salman has said the aim is to reduce unemployment from 13.1 percent to 8.5 or 9 percent in four years.

But with authorities trying to silence labor voices, activists fear the new push will repeat the problems of the past, when investment fueled growth but benefited only a small circle of businesses close to the government and military, leaving the population largely impoverished and the work force unskilled and unprotected. Growth from 2004-2010 was "buoyant," averaging 5.5 percent a year, but failed to generate enough jobs, the International Monetary Fund said in a recent report.

In the partial or full sell-offs of some 380 state-owned companies in the 1990s and 2000s, some investors dismantled firms, sold off their land assets or used them as collateral to secure large loans, while letting workers go. Other investors milked tax breaks, then dumped the companies once the incentives ended. The process was plagued by bad deals that undervalued state enterprises. Courts have ordered at least a half dozen companies renationalized because of undervalued deals, and workers have raised court cases over 60 others.

"They are continuing to sell Egypt," said Hoda Kamel, a labor activist with the Egyptian Center for Economic and Social Rights who monitors strikes.

"There is no fair labor law, no free union law, and there is no change in economic policies," she said. "Factories are shutting down and there are fewer jobs while the informal sector is gigantic … When the revolution happened, people thought they will get their rights. But policies remained the same."

Egypt's workers remain one of the country's better organized sectors, despite repeated government crackdowns. Labor protests and strikes were critical in undermining the regime of Hosni Mubarak, most dramatically when workers tore down his picture in a 2008 strike in the Nile Delta city of Mahalla. During the 2011 uprising, workers backed the protests with strikes that virtually shut down the country and hastened Mubarak's ouster.

Hundreds of independent unions sprang up after Mubarak's fall, challenging the one labor federation, which had effectively worked as a government arm. Strikes have continued, even as successive governments have tried to stamp them out, whether by regulation, law or crackdowns. Sisi has repeatedly demanded that workers and other protesters set aside their demands in the interest of stability.

Even after a 2013 law virtually criminalized all public political gatherings, labor groups pushed ahead with 249 worker protests in the first quarter of 2014 — the majority of the total 354 recorded protests in that period, according to the Egyptian Center for Economic and Social Rights. Labor activists also won a court order to increase the minimum wage.

One of Egypt's most prominent businessmen, Ahmed Heikal, said it's unfair to compare privatization to the push for foreign direct investment.

Privatizing existing assets is "tricky," he said in an interview with The Associated Press. But FDI is "is very clear. The need to build from scratch industrial entities, service entities is clear."

He said a major change now was that the government has largely lifted decades-old fuel subsidies, which encouraged energy-intensive businesses like steel, fertilizer and cement. The higher energy costs will draw higher quality investors, not just ones betting on cheap fuel, and labor will benefit, he said.

In the past, the country effectively "took money and put it in helicopters and climbed to 3,000 meters and dropped it. We thought that the money will be distributed to deserving people," he said. "There is a big fallacy all over the world that the subsidies go to those who deserve it. It goes to those who consume more energy, which are the rich."

Heikal's company al-Qalaa Holdings is a major shareholder in one of the country's biggest new investment projects, a $3.7 billion refinery that will employ thousands and reduce imports of diesel fuel.

Investors have had their own complaints about Egypt's extensive bureaucratic red tape and complicated government procedures, a lack of skills among workers, and a judicial process that gave wide leeway to bring lawsuits that were often dragged out. Recently, the government changed the law to prevent third-party lawsuits over contracts between the state and investors, raising concerns it will be more difficult to challenge corrupt deals.

Dina H. Sherif, a venture capitalist who promotes small businesses with social impact and who is on a seven-member committee advising Sisi on economic development issues, said the government and private sector now realize that labor issues must be addressed more creatively.

She said she hopes the conference will not just draw investors but also create "a new level of discourse that will include a lot more innovation and a lot more inclusivity."

A proposed investment law would offer non-tax incentives to new investors in labor-intensive industries, an attempt to encourage job creation. But the draft law still doesn't specify what incentives there will be.

And while the government consulted some 180 institutions on the new law, according to Salman, labor activists were not among them. Labor unions and the government are already at odds over new laws in the works on workers' rights and on regulating unions.

Kamal Abbas, a leading figure in the independent union movement, says the government hasn't learned from previous experience and wants to continue wooing investors with "cheap labor with no powerful union representation that would cause pressure or disturbance."

The government, he said, is "ruling out that the relationship between employers and workers could be one of dialogue … instead of one of submission."