A Bedouin siege of an international peacekeepers camp in Egypt's Sinai underscores the ruling military's weak grip over the restive frontier territory more than a year after an uprising shook the country.

On Friday, eight days into the siege in the north of the peninsula, the ruling generals cajoled the machinegun-toting tribesmen into ending the stand-off with a promise to look into their grievances.

The Bedouin said they would give the military a month to meet their demand for the release of jailed tribesmen, some convicted on terror charges. None of the peacekeepers, tasked with monitoring a treaty with Israel, was harmed.

The stand-off came after a series of embarrassments for the tough-talking military rulers, who appeared incapable of preventing 13 bombings of a vital pipeline carrying gas through Sinai to Israel and Jordan.

The peninsula is a major route for drugs smuggling, human trafficking and migrants into Israel, as well as weapons supplies to the neighboring Palestinian Gaza Strip.

Ever since an uprising overthrew President Hosni Mubarak more than a year ago, throwing his feared security services into disarray, the region has grown even more distant from Cairo's grasp.

Bedouin have briefly kidnapped tourists and foreign workers to press for the release of jailed tribesmen, and Islamist radicals have attacked police stations and posts.

After trying with questionable success to root out Bedouin militants last year with a military-led operation, the authorities are now trying their hand at negotiations, which some say merely give the radicals more purchase.

The military has pardoned 18 Bedouin outlaws sentenced by military tribunals in absentia, while a state security court ordered a new trial for five Bedouin accused of deadly bombings in two Sinai tourist resorts in 2004.

For decades, a robust security approach to dealing with unrest in the mountainous and desert peninsula had not only failed the central government, but allowed the problem to fester, analysts say.

Between 2004 and 2006, dozens of tourists and Egyptians were killed in a series of bombings in the Sinai. Mubarak's police rounded up thousands of Bedouin and tortured some of them, rights groups said.

"The roots of grievances in Sinai are long standing, and the extent of government authority in Sinai has always been tenuous," said Michael Wahid Hanna, an Egypt expert at the US think tank The Century Foundation.

"There is a level of discrimination involved, an adversarial relationship with Bedouin in Sinai. That dysfunctional relation has produced a security mindset in how authorities deal with the Bedouin," he said.

Egypt, which fought devastating wars with Israel to regain the peninsula after losing it in the 1967 Six-Day War, relies on its lucrative beach resorts for tourism revenues and employment.

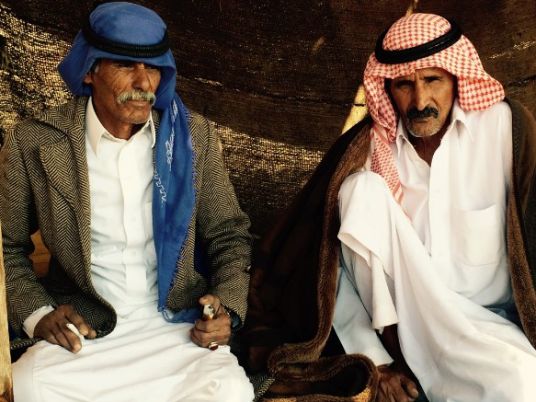

The Bedouin, less than half of the peninsula's population of approximately 500,000, see little of that money and opportunity.

Many are impoverished and illiterate. Along the border with Israel, they bitterly contrast their barren side with Israel's lush green vista.

In official statements both their leaders and Cairo politicians are careful to emphasize they are all Egyptian, but the veneer of camaraderie masks contempt and discrimination, Bedouin activists say.

"They say Sinai is Egyptian, but I don't think they really believe Sinai is Egyptian," said Bedouin rights activist Yahya Abu Nasira, who was jailed for thirty months for his political activism under Mubarak.

"They always doubt our loyalty," he said.

Mohammed Fadel Shosha, who was the governor of North Sinai and until recently the governor of South Sinai, said developing the provinces was crucial to quelling the unrest but that creating infrastructure is difficult.

"Development in a place like Sinai is expensive. Agricultural development, for example. Despite the Salam canal, you need secondary canals, which can cost for example LE500 million," he said.

A station to elevate the water to the mountainous areas was estimated at LE2 billion two years ago, he added.

Investors "have capital but they're worried about it. But when he finds there is a government incentive to take the risk, he can invest," Shosha said.

The military-appointed cabinet has promised to help develop the region, but activists say nothing has improved since the uprising.

"Nothing happened after the revolution. It's deteriorated. There is no such thing as government in Sinai. It is a ship without a captain," said Abu Nasirah.