In 1922, Howard Carter made the most exciting archaeological discovery of the 20th century. Working with backing from George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon, the Egyptologist uncovered a tomb just west of Luxor and the Nile River, in the Valley of the Kings.

It was the most intact tomb of its kind ever found, relatively untouched by the grave robbers who’d looted nearby crypts in the intervening millennia. Because the ancient Egyptians had buried their dead with everything they’d need for the afterlife, there was plenty to steal.

The tomb, Carter discovered, belonged to pharaoh Tutankhamun (ruled ca. 1334-25 B.C.E.) and housed more than 5,000 objects that ranged from the magnificent to the prosaic: Tut’s solid gold inner-coffin, sandals, statues, jewelry, textiles, oars for navigating the underworld and even linen loincloths.

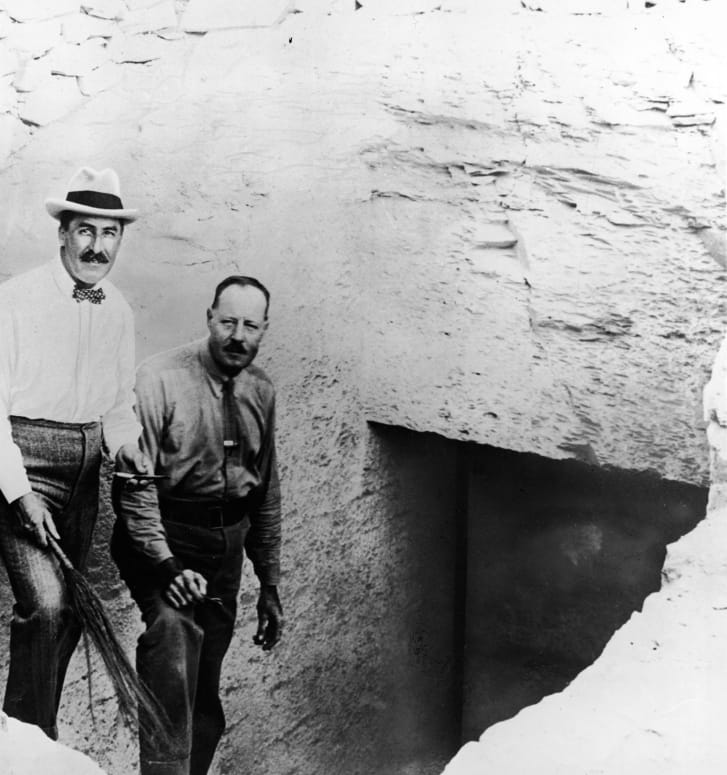

British Egyptologist Howard Carter (left) pictured on the steps leading to Tutankhamun’s tomb with his assistant Arthur Callender. Credit: Pictorial Parade/Archive Photos/Getty Images

The find was exciting on its own; a canny media ploy gave the excavation additional publicity. British newspaper The Times paid £5,000 for exclusive access to the tomb, one of the first paid scoops in history. The public frenzied.

“From the discovery in 1922, this vision of magnificence of pharaonic culture captured the imagination of just about every school child the world over,” said Adam Lowe, the founder of digital conservation lab Factum Arte, which completed a three-dimensional recreation of the tomb in 2014. King Tut, a chronically ill child ruler who died at around 19 years old, was an overnight celebrity whose star has yet to fade.

Carter’s discovery was just the beginning of King Tut mania. Herbert died in 1923, shortly after entering the tomb — most likely from an infected mosquito bite — and a series of people connected with him and Carter suffered mysterious traumas. Rumors of King Tut’s curse circulated.

Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus pictured at Cairo’s Egyptian Museum in 2017. Credit: MOHAMED EL-SHAHED/AFP/Getty Images

Beginning in the 1960s, traveling exhibitions of antiquities from the tomb created a new global sensation. An ongoing show, which started at the California Science Center in 2018, moved on to Paris’s Grande Halle de La Villette in Paris, where it broke attendance records for a French art show — the previous record-holder was also a King Tut exhibition — and sold around 1.4 million tickets. The show has just opened at London’s Saatchi Gallery in November as part of its 10-city world tour.

The general public’s embrace of the boy pharaoh shows no signs of relenting, but issues of ownership and repatriation surrounding Tut-related objects still rage.

Auction anxieties

In June, Egypt attempted to stop Christie’s from selling a quartzite sculpture with King Tut’s features. The country alleged that the antiquity had been looted from the Temple of Karnak in Luxor around 1970 — the year UNESCO instituted a treaty aimed at establishing measures for preventing cultural thefts and provisions for restitution.

The auction house disagreed, claiming it had established appropriate provenance and that the statue was in the private collection of Prinz Wilhelm von Thurn und Taxis by the 1960s. Christie’s went ahead with the July auction and sold the disputed object for nearly $6 million. Days later, Egypt said it would sue Christie’s. The brouhaha typifies the disagreements that still pervade the market for Egyptian antiquities. (Christie’s declined to comment for this article.)

An Egyptian brown sculpture of Tutankhamen sold for nearly $6 million at Christie’s auction house.

Attorney Leila Amineddoleh, who’s working with the Greek government on similar repatriation issues, called the “alleged provenance” of the sculpture “inaccurate or highly questionable.” “It is not acceptable,” she said, “for art market participants to turn a blind eye towards problematic provenance or ignore red flags.”

Amineddoleh also noted an increase in looted Egyptian antiquities since political uprisings began in the country in 2011. She added that “plunder is often a crime of opportunity.”

Egypt, in fact, had measures in place as early as 1835, when it banned other countries from removing objects from its borders without approval. In 1983, the country instituted its most stringent cultural heritage rule to date: Law No. 117, which entirely abolished antiquities exports. Up until that point, countries excavating legally in Egypt could keep half of what they dug up — with one big exception: Cairo would keep all the contents of any unplundered royal tomb, which meant that the entirety of King Tut’s burial chamber stayed in the country. Yet German Egyptologists have alleged that Carter stole objects from the tomb, which are now scattered around the world.