Underfed and chained up for endless hours, many elephants working in Thailand’s tourism sector may starve, be sold to zoos or be shifted into the illegal logging trade, campaigners warn, as the coronavirus decimates visitor numbers.

Before the virus, life for the kingdom’s estimated 2,000 elephants working in tourism was already stressful, with abusive methods often used to ‘break them’ into giving rides and performing tricks at money-spinning animal shows.

With global travel paralyzed the animals are unable to pay their way, including the 300 kilograms (660 pounds) of food a day a captive elephant needs to survive.

Elephant camps and conservationists warn hunger and the threat of renewed exploitation lie ahead, without an urgent bailout.

“My boss is doing what he can but we have no money,” Kosin, a mahout — or elephant handler — says of the Chiang Mai camp where his elephant Ekkasit is living on a restricted diet.

Chiang Mai is Thailand’s northern tourist hub, an area of rolling hills dotted by elephant camps and sanctuaries ranging from the exploitative to the humane.

Footage sent to AFP from another camp in the area shows lines of elephants tethered by a foot to wooden poles, some visibly distressed, rocking their heads back and forth.

Around 2,000 elephants are currently “unemployed” as the virus eviscerates Thailand’s tourist industry, says Theerapat Trungprakan, president of the Thai Elephant Alliance Association.

The lack of cash is limiting the fibrous food available to the elephants “which will have a physical effect”, he added.

Wages for the mahouts who look after them have dropped by 70 percent.

Theerapat fears the creatures could soon be used in illegal logging activities along the Thai-Myanmar border — in breach of a 30-year-old law banning the use of elephants to transport wood.

Others “could be forced (to beg) on the streets,” he said.

It is yet another twist in the saga of the exploitation of elephants, which animal rights campaigners have long been fighting to protect from the abusive tourism industry.

– ‘Crisis point’ –

For those hawking a once-in-a-lifetime experience with the giant creatures — whether from afar or up close — the slump began in late January.

Chinese visitors, who make up the majority of Thailand’s 40 million tourists, plunged by more than 80 percent in February as China locked down cities hard-hit by the virus and banned external travel.

By March, the travel restrictions into Thailand — which has 1,388 confirmed cases of the virus — had extended to Western countries.

With elephants increasingly malnourished due to the loss of income, the situation is “at a crisis point,” says Saengduean Chailert, owner of Elephant Nature Park.

Her sanctuary for around 80 rescued pachyderms only allows visitors to observe the creatures, a philosophy at odds with venues that have them performing tricks and offering rides.

She has organised a fund to feed elephants and help mahouts in almost 50 camps nationwide, fearing the only options will soon be limited to zoos, starvation or logging work.

For those restrained by short chains all day, the stress could lead to fights breaking out, says Saengduean, of camps that can no longer afford medical treatment for the creatures.

Calls are mounting for the government to fund stricken camps to ensure the welfare of elephants.

“We need 1,000 baht a day (about $30) for each elephant,” says Apichet Duangdee, who runs the Elephant Rescue Park.

Freeing his eight mammals rescued from circuses and loggers into the forests is out of the question as they would likely be killed in territorial fights with wild elephants.

He is planning to take out a two million baht ($61,000) loan soon to keep his elephants fed.

“I will not abandon them,” he added.

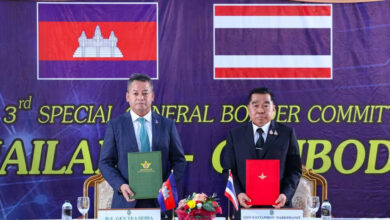

Image: ELEPHANT NATURE PARK/AFP / Handout With global travel paralysed the animals are unable to pay their way, including the 300 kilograms (660 pounds) of food a day a captive elephant needs to survive