For 94-year-old Louise Irving, who suffers from dementia, waking up every day to a video with a familiar face and a familiar voice seems to spark a flicker of recognition.

"Good morning, merry sunshine, how did you wake so soon?" Irving's daughter, Tamara Rusoff-Hoen, sings in a video playing from a laptop wheeled to her mother's nursing home bedside.

As the five-minute video plays, with stories of happy memories and get-togethers, Irving beams a bright smile before repeating the traditional family send-off.

"Kiss, kiss … I love you."

Such prerecorded messages from family members are part of an apparently unique pilot program at the Hebrew Home at Riverdale aimed at helping victims of Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia break through the morning fog of forgetfulness that can often cause them agitation and fear.

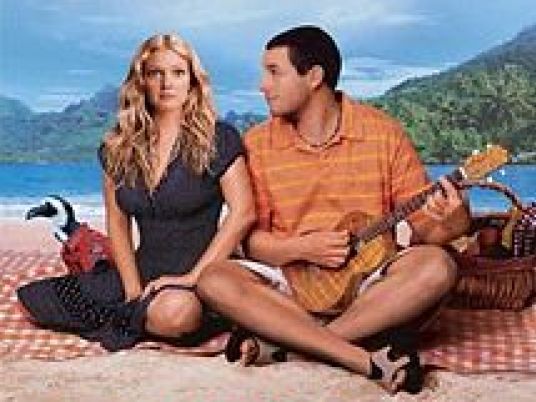

It's an idea borrowed from an unlikely place: the 2004 Adam Sandler movie "50 First Dates," in which a brain-injured woman played by Drew Barrymore loses her memory every day and a suitor played by Sandler uses videos to remind her about him.

"It was fluff, but it made me think, 'How could that translate to our residents with memory loss?'" says Charlotte Dell, director of social services at the home.

"We're looking to see if we can set a positive tone for the day" without using drugs, she says. "What better way to start the day than to see the face and hear the voice of someone you love wishing you a wonderful morning?"

As in the movie, every day is a new day, and the video becomes part of the morning routine. Relatives who take part are urged to say good morning, use memory-triggering personal anecdotes and remind the residents that attendants will be helping them get dressed and ready for the day.

Alzheimer's disease and other dementias afflict a growing number of Americans as baby boomers age and people live longer. The Alzheimer's Association says more than 5 million Americans have Alzheimer's.

The personal morning video appears to be a new wrinkle in dementia caretaking.

"Memory tools like videos and photos get a lot of use, but to have a couple of minutes with a loved one as a way to start out the day, I haven't heard of anything quite like that," says Ruth Drew, director of family and information services for the association.

Robert Abrams, a geriatric psychiatrist at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, called the program "both innovative and thoughtful."

"You've got a group of people with dementia who don't really grasp the nature and purpose of their surroundings or the circumstances that compelled them to be there," Abrams says. "Consequently, they're alone and at sea and feel frightened and even abandoned by family."

Experts caution, however, that Alzheimer's patients vary widely, and techniques that may work beautifully for one might not work for another.

The program at the Hebrew Home is limited to residents in the early and moderate stages of dementia who are likely to recognize the people in the video and understand what they say.

"Do we know for sure that they know, this is my daughter, this is my son? No," Dell says. "But they recognize them as somebody they care about and love."

The program is starting with residents who are known to staff as difficult in the morning and who refuse care, a description that Rusoff-Hoen acknowledges fits her mother.

"Some of her agitation comes from, 'Who the heck are these people? Why am I here?'" she says.

Although Rusoff-Hoen, who lives a couple of hours away in Ghent, visits her mother three days a week, she said the video program helps fill in the gaps. "I am there with my mom, loving her and wishing her a wonderful day and helping her to feel better because there's not a lot I can do for her," Rosoff-Hoen said.

The Hebrew Home plans to evaluate the program after this month and may expand it to more of the several hundred residents in its memory-care "neighborhoods." Dell says anecdotal evidence from the staff is "very positive."

Irving's son-in-law, Mihai Radulescu, also made a video for her. In it, he kids her about being "a delinquent" because she once worked for a bootlegger.

On the recording, he repeatedly reminds Irving, "I know where you are. … I will always find you," because she has expressed a deep fear of being lost.

Other videos include a woman reminding her mother, in Spanish, to eat and take her medications, then tearing up at the end and saying, "I love you, Mom."

On another video, a man encourages his mother, saying, "You used to tell me that attitude is everything. … You said that it's best to start off on the sunny side of the street."