MUMBAI/NEW DELHI, India (Reuters) – When artist Rachita Taneja heads out to protest in New Delhi, she covers her face with a pollution mask, a hoodie or a scarf to reduce the risk of being identified by police facial recognition software.

Police in the Indian capital and the northern state of Uttar Pradesh – both hotbeds of dissent – have used the technology during protests that have raged since mid-December against a new citizenship law that critics say marginalizes Muslims.

Activists are worried about insufficient regulation around the new technology, amid what they say is a crackdown on dissent under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, whose Hindu nationalist agenda has gathered pace since his re-election in May.

“I do not know what they are going to do with my data,” said Taneja, 28, who created a popular online cartoon about cheap ways for protesters to hide their faces. “We need to protect ourselves, given how this government cracks down.”

Critics also accuse authorities of secrecy – highlighting, for instance, that the software’s use during Delhi protests was first revealed by the Indian Express newspaper.

India’s home ministry did not immediately respond to requests for comment on facial recognition technology.

Modi’s government has rejected accusations of abuse during demonstrations, and accused some protesters of stoking violence.

A spokesman for his ruling Bharatiya Janata Party had no immediate comment on concerns over the use of the technology and referred questions to the government.

But police said worries about facial recognition were unwarranted.

“I’m only catching targeted people,” said Rajan Bhagat, a deputy commissioner of police at Delhi’s Crime Records Office. “We don’t have any protesters’ data, nor do we plan to store it.”

He declined to give details of potential arrests, however.

When it comes to surveillance, India trails far behind neighboring China. New Delhi, for example, has about 0.9 CCTV cameras for every 100 people, versus about 11.3 per 100 in China’s commercial hub of Shanghai, a 2019 report by PreciseSecurity.com showed.

The Delhi police use Indian startup Innefu Labs’ facial recognition software AI Vision, which also includes gait and body analysis.

“If somebody is throwing stones at a police officer, doesn’t he have a right to take a video and identify him?” said Innefu co-founder Tarun Wig, 36.

Police in about 10 Indian states use Innefu products, Wig said.

Financial fraud analytics are among the services provided by Innefu, which published a social media analysis in January that concluded much criticism of the new citizenship law came from archenemy Pakistan to “destabilize the harmony” of India.

The company is representative of homegrown artificial intelligence startups tapping into booming demand for facial biometrics in India, in part thanks to their testing on Indian faces and more affordable prices.

A few established foreign firms, such as Japanese telecommunications and IT giant NEC Corp, also operate in India, where the market is expected to grow from about $700 million in 2018 to more than four billion dollars by 2024, TechSci Research said in a report.

UTTAR PRADESH ARRESTS

Facial recognition helped police in Uttar Pradesh, home to 220 million people, detain a “handful” of the more than 1,100 people arrested for alleged links to violence during protests, said O P Singh, its police chief who retired last month.

Singh gave no details but said the technology helped cut the numbers of wrongful arrests and highlighted the state’s extensive database of more than 550,000 “criminals”.

Rights groups have decried what they call excessive force in Uttar Pradesh, which has the largest number of representatives in parliament and is governed by hardline Hindu priest and Modi ally Yogi Adityanath.

The state says tough policies have restored order.

Startup Staqu is supplying its product, the Police Artificial Intelligence System, to police in eight states, including Uttar Pradesh, says the firm’s co-founder, Atul Rai.

Fears of mass surveillance in India were exaggerated, said Rai, 30, citing difficulties in collecting information because of India’s large population of 1.3 billion. But there was a need for regulation to avoid potential problems, he added.

Police should have clear rules on use of facial recognition technology and there should be disclosure of the software’s audits and algorithms, the non-profit Internet Freedom Foundation says.

“What India is seeing is a kind of personal data Wild West,” said its executive director Apar Gupta.

PAN-INDIA FACIAL RECOGNITION

Law enforcement across India could soon be using facial recognition technology.

Modi’s government is seeking bids to create a nationwide database, the National Automated Facial Recognition System, to help match images captured from CCTV cameras with existing databases, including those of passport and police authorities.

A foreign firm is expected to win the contract, since the bid terms require firms’ algorithms to be evaluated by the United States’ National Institute of Standards and Technology. Both Innefu and Staqu said they were not bidding.

Japanese firm NEC’s India subsidiary helped develop the Aadhaar biometrics identity system and supplies facial recognition technology to law enforcement in the diamond industry hub of Surat in western Gujarat state.

The software has not been used during protests, however, the city’s police commissioner, R B Brahmbhatt, told Reuters.

NEC spokesman Shinya Hashizume declined to comment on whether the company was bidding to build the nationwide database.

The system will boost police efficiency, says the National Crime Records Bureau, which launched the tender that closes at the end of March.

But critics say it puts India on the path to China-style mass surveillance.

Worried about being identified, a 21-year-old Muslim protester in New Delhi has adopted the pseudonym Moosa Ali and sometimes covers his face with handkerchiefs.

“We don’t know enough about these things, but we are trying to take some precautions,” he said.

Reporting by Alexandra Ulmer, Zeba Siddiqui

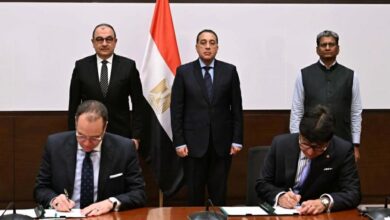

Image: Police officials sitting atop a bus take videos of demonstrators during a protest against a citizenship law, in New Delhi, India, February 10, 2020. Picture taken February 10, 2020. REUTERS/Danish Siddiqui