Like many a bumbling tourist, this traveler was perplexed by the unexpected. People dressed differently, ate differently, wrote differently, did everything differently. The river flowed not from north to south but from south to north.

But what was most perplexing to the fifth century BC Greek historian Herodotus when he visited Egypt was the role of women. “Women attend market and are employed in trade, while men stay at home and do the weaving,” he wrote.

The Egyptians, he concluded, “in their manners and customs seem to have reversed the ordinary practices of mankind.”

The women of ancient Egypt—the mighty and the modest—were considered equal to men, said Egyptologist Valentina Santini. “They could divorce. They could own property. They had many rights that women in subsequent civilizations didn’t have.”

Santini was showing me around Turin’s Museo Egizio — Egyptian Museum — the oldest museum dedicated to ancient Egypt, founded in 1824.

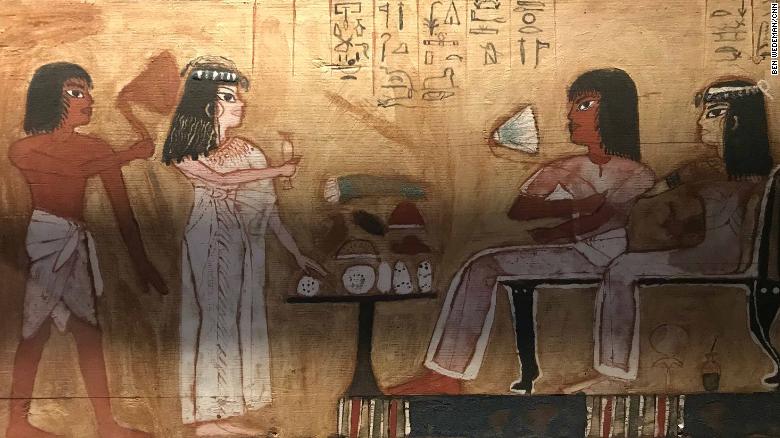

We were in a room dedicated to Merit, a woman who lived around 3,400 years ago during Egypt’s New Kingdom period. She died at the age of 25 from causes unknown. The boxes that contained her toiletries and other possessions are painted with images of a confident woman side by side with her architect husband, Kha, giving offerings to the gods and greeting visitors.

The variety of expensive goods she was buried with—a large wig made of human hair, loaves of bread, jewelry, toiletries, clothing—attests to her importance.

In the same room is a white limestone statue of a woman — Nefertari — and her husband, Pendua. They are the same size, same height, each with an arm draped on the other’s shoulder.

A depiction of the kind of equality that no doubt left Herodotus perplexed.

“Probably he was quite upset by seeing what was happening just next door, because maybe Greek women could take an idea and get the same kind of opportunities their Egyptian colleagues had,” remarked Evelina Christillin, president of the Museo Egizio Foundation.

The Egyptian pantheon was full of fearsome goddesses, including Sekhmet—the name means “the powerful one.” Sekhmet had the body of a woman and the head of a lioness.

And Ancient Egypt boasted a series of powerful queens, including Hatshepsut and Cleopatra.

For ordinary Egyptian women life was short, and difficult. Childbirth often proved deadly. Yet they did enjoy a level of legal protection, including prenuptial agreements.

“Women had a social status which was very well defined,” museum director Christian Greco told me. “We have here some wedding contracts, where it stated very clearly what a man should guarantee in terms of silver and other commodities in case of divorce.”