Katie Weimer, a biomechanical engineer based in Colorado, was challenged by her mentor to think bigger — to use advances in regenerative medicine to “improve the future of mankind.”

That challenge provided a spark in Weimer. She thought of her mother who died of breast cancer at the age of 50 when Weimer was just 15 years old.

All these decades later, Weimer’s mom has never been too far from her heart. With advances in regenerative medicine and lab-created biotissue, Weimer had an idea on how to bring hope to breast cancer survivors around the world.

What if there was a way, she wondered, to 3D print bio-friendly breast tissue material that could restore dignity to survivors after a lumpectomy, the targeted removal of the cancerous tissue?

“The reality is so many women must live with a reminder of the cancer they had every single day,” Weimer, 43, said. “That is not good enough. There must be a better way.

“My team and I believe every woman has the right to get a breast reconstruction after cancer treatment — one that allows a woman to be whole again.”

She also said women deserve an implant that doesn’t “come with an FDA box warning,” a stringent safety notice the US Food and Drug Administration puts on current implants warning of possible cancer risks.

3D-printing biotissue

More than 300,000 women in the United States are diagnosed with breast cancer every year, according to the American Cancer Society. It remains one of the most common — and deadliest — cancers in women, claiming the lives of about 40,000 women annually. Worldwide, an estimated 2.3 million women are diagnosed with breast cancer, with nearly 670,000 dying from the disease every year, according to the World Health Organization.

For most, treatment requires a lumpectomy or a mastectomy, the removal of all the breast. Some 170,000 lumpectomies are performed in the US every year, and about 20% of women need to undergo a second procedure.

Even when the cancer is removed by lumpectomies, the breast is often left permanently scarred.

“Sadly, the standard of care is to treat the disease, but not the deformity,” Weimer said. “Doctors do a good job of removing the cancer, but unfortunately women are left with a divot in their breast. And it has huge psychological impacts on survivors.”

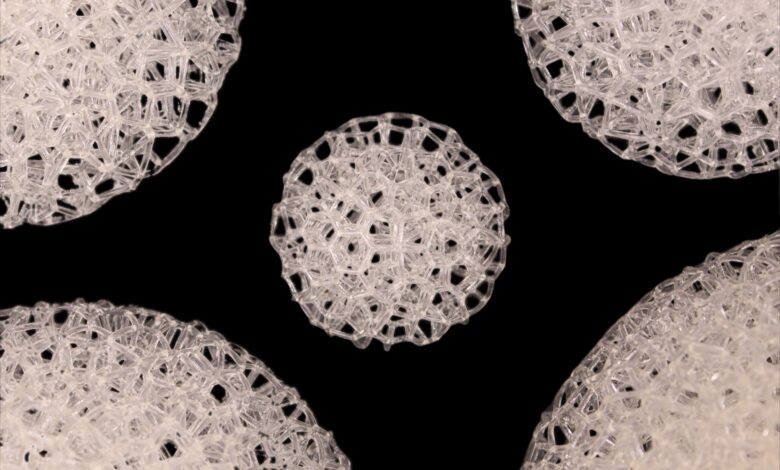

Seeking to find a better way, Weimer launched her Colorado startup, GenesisTissue, in 2024. The solution she and her team devised: Build 3D-printed breast-tissue “scaffolds” made from advanced, cell friendly bioprintable materials that the body won’t reject. Surgeons would extract a patient’s fat cells through liposuction, inject those cells into the scaffold, and once implanted those cells grow into natural tissue.

“The ideal solution would be to implant the scaffold at the time of cancer tissue removal,” Weimer said. “The scaffold protects the injected fat graft from the pressures and forces of the breast and restores the breast’s shape.”

This reconstruction, Weimer said, would allow a patient’s body to heal itself, from its owns cells, and the scaffold would disappear over time, allowing a survivor to become “whole again.” It could also allow breast surgeons to play a role in the reconstruction, she said, beyond removing the cancer.

Every case would be personalized to each individual patient with computer scans providing exact specifics about the tumor size, then that data would be sent to a 3D printer to make the biofriendly scaffold.

“It’s pre-planned and pre-sized to fit the patient. We’re not taking an off-the-shelf component and forcing it to fit,” Weimer said. “There’s no long-term rejection risk, no worrying about this foreign object in your breast. You’re just left with your own tissue.”

Her technology isn’t commercially available yet. Benchtop data and preliminary preclinical data have shown promising results that she hopes will lead to clinical trials.

“At Genesis Tissue,” she said, “we are working every day fighting for breast cancer survivors and their right to a breast reconstruction that regenerates into their own breast tissue — and lasts a lifetime.”

Soaring uses of bioprinted medicine

There currently are two types of breast implants approved for sale in the United States: saline-filled and silicone gel-filled. The Food and Drug Administration in 2020 issued a boxed warning about how “breast implants are not considered lifetime devices” and “breast implants have been associated with the development of a cancer of the immune system called breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma.”

Weimer said her personal mantra is that the medical field should “stop implanting industrial materials in human breasts,” especially at a time when the field of bioprinting and regenerative medicine is making huge strides in patient care.

Breakthroughs in recent years have included a patient in South Korea receiving a landmark 3D-printed windpipe built from cartilage and mucosal lining in 2024. At the University of California San Diego, researchers are developing “functional, patient-specific livers using 3D printing.” Researchers at Penn State University in 2025 received a $3 million federal grant to use 3D printers to “use living cells and biomaterials to build tissue-like structures.”

In the breast tissue space, Harvard researchers have been studying ways to utilize 3D printing to make vascularized tissue for breast reconstruction, as have researchers at the French medtech company Lattice Medical and Australian innovator Anand Deva.

Weimer acknowledges she’s not the first researcher in this space. She believes all of them — scientists, engineers, researchers — are in a shared race of sorts because the demand and need are so critical.

“It’s a movement now,” she said.

Weimer has been at the forefront of advanced surgical planning and anatomical modeling, utilizing 3D printing since 2007, first at a company called Medical Modeling and then at 3D Systems. As a biomechanical engineer, she has helped guide surgeons in countless surgeries, printing models that provided better accuracy in the operating room and improved patients’ lives. The most famous case she worked on was the 27-hour separation surgery of Jadon and Anias McDonald, twins born conjoined at the head, documented by CNN in 2016.

Dr. Oren Tepper, the renowned plastic surgeon who was the lead on the twins’ case, has known Weimer for two decades and has worked with her on multiple surgeries.

“She’s one of the most talented biomedical engineers I’ve ever met,” said Tepper, an associate professor of plastic surgery at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and a specialist in 3D surgical innovation and tissue regeneration. “She’s the perfect person to lead this front. Her expertise is not just in 3D printing, but the application of this technology in a way that truly translates into the operating room and patient care.”

Like most groundbreaking medical technologies, the biggest hurdles at this point remain the regulatory process to get FDA approval. Rigorous testing and research continue, but Tepper said the technology Weimer is working on would be a “game changer” in the world of breast reconstruction.

Weimer was mentored by Charles Hull, the inventor of 3D printing and chief technology officer of 3D Systems, the company he founded in 1986. He encouraged Weimer and other engineers in 2021 to push the limits of invention — to use their intellect to serve humanity in a big way.

At 86, Hull said he is proud that Weimer heeded his call. He’s not surprised, he said, because “she’s made a career out of helping people.”

“As the father of 3D printing,” Hull told CNN, “it has been an honor to see an engineer of Katie’s caliber take my initial invention and utilize it in a new way to hopefully benefit women around the world in the not-so-distant future.”

When and if that time comes, Weimer believes she will have honored the mom she lost far too early, the woman whose wisdom and guidance she has longed for since her death in 1998.

“Her life, her illness, and her selflessness as a human are a big reason why I believe innovation matters,” she said. “Only now, nearly 30 years later, can I look back and see how her cancer journey affected my career.”

Losing her mom was “such a transformative moment;” Weimer now hopes her journey results in transformative change for women everywhere.